|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

FALL 1989, VOL. 2, ISSUE 2, Part TWO

The

Hay Barrack: A Dutch Favorite

How long do barracks last? They were apparently intended

as long-term appurtenances to the barn. A natural death would eventually

come from rotting in the ground. Barracks in New Jersey have survived

for up to 50 years.

One with chestnut posts - very rot resistant - lasted

just over 50 years before having its posts replaced. Replacing

the thatch at regular intervals would appear to be the only essential

maintenance required, a further recommendation for the use of this

easily erected structure.

In 1977, at least two New Jersey farmers remarked

on the usefulness of hay barracks on their farms, saying that they

were "very handy" (McTernan 1978:69), presumably in the

sense that they are conveniently located, accessible (open sided),

structurally flexible (roof moves to fit need) and functionally

flexible (storage of different crops, vehicles, or anything else).

In New Jersey, Long Island, Schoharie and the Hudson Valley, barracks

were being built well into the present century, later than any

other Dutch structure. The historian Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker

in 1938 commented on this persistence:

"In the fields adjacent to some of the old

Dutch barns one is interested to see a unique type of haystack,

consisting of four or five heavy poles planted in the ground

at equal intervals, and covered by a roof which can be raised

or lowered according to the amount of hay . . . It is a remarkable

illustration of the persistence of inheritance that the descendants

of the Dutch should have clung to the adjustable roof haystack

for three centuries even in localities where Dutch architecture

and most practices have long since vanished"

(Wertenbaker 1938:64).

Recently surviving New Jersey examples were recorded

by Don McTernan in 1978, and a barrack near Linlithgo, Columbia

County, NY, stood until 1985. The New Jersey barracks were not

large barracks in the sense of having five or more poles or being

40' high. They were smaller four-pole structures presumably reflecting

the functional needs of latter day farms in that region.

This persistent usefulness of barracks must not

only be ascribed to their "handyness" but also to how

easily they can be erected and cared for. Some sense of their cheapness

can be gleaned from an inventory of a 1654 farm west of Castle

Island just south of Beverwyck (Albany). The farm's house was valued

at 600 guilders, the barn at 1100 and the three barracks, "exclusive

of hardware" (presumably a jack) at only 60 guilders (Van

Laer 1908:775).

Two centuries later in the American Agriculturalist,

an article (June 1879, p. 222) touted the usefulness of "cheap

and easily made barracks", describing features unchanged during

that 200year period: ". . . four square tapered poles 20 feet

long set in the ground 4 feet, spaced 16 feet apart. A roof frame

of 'sills' (plates) half lapped and pinned at each corner; light

poles for rafters fitted into 2 inch holes, gathered at the apex

with an iron band or bound by fence wire." The article continues, "Some

cross strips of flattened poles or split hoop-pole stuff, are then

pinned with half inch pine, or bound to the rafters with hickory

or white oak withes, softened and toughened in a fire. The frame

is then thatched with straw or bog-hay. . . . The result is a stiff,

substantial structure, which will hold 8 to 10 tons of hay or sheaf-grain,

and preserve it as if it were in the most costly barn. In filling

a barrack of this kind, the hay may be built out 2 feet each way

wider than the roof, making the stack 20 feet square, up to near

the top, when it may be gradually drawn in, and raked down from

top to bottom, the loose hay being thrown upon the top. The root

is then let down upon the hay, which is thus completely protected

from the weather. The roof is raised or lowered by means of the

lever. . . this is rested upon a pin placed in a hole in the post,

and the pivoted end is placed under the corner of the roof, which

is raised by depressing the handle of the lever."

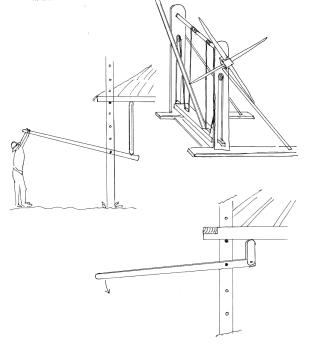

This fulcrum device is the simplest of various arrangements

which have been described or illustrated for raising the barrack

roof. The fulcrum works when the post holes are perpendicular to

the plate. A variation still in use in New Jersey consists of a "sweep",

a "temple" (spacer), and a bolt (see illustration).

<-Counterclockwise: <-Counterclockwise:

Winding jack after van Berkhey (1810).

Fulcrum jack after American Agriculturalist (1879). Sweep and temple

jack after McTernan (1978). Drawings by Roderic Blackburn, 1989.

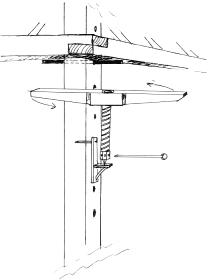

Other arrangements included a winding device and

a screw jack. The latter is the type mentioned in early American

documents. "A barrack with four posts. . . 1 jackscrew for

the hay barrack" was listed in the 1643 inventory of the farm

Vredendael (Reg. of Provo Sect. 1638-42 II p.136).

A Dutch description of the technique for filling

a hay barrack explains further how hay barracks were utilized.

Filling a hay barrack was no hit-or-miss operation. On the bottom

was put a layer of old hay to prevent hay from molding on the bottom

and smelling. The hay was rolled around the fork and put around

the outside perimeter, a fork-full at a time. Concentric circles

of rolled hay were made until a layer was completed. When one layer

was full and flat, then the next layer was added. A man who did

this well was called a "master at layering."

After three or four weeks, the hay was pressed together

if it had not compressed of its own weight. The hay breathed out

a watery liquid and sometimes had a burning smell which was a sign

that something was smouldering inside. This situation was not allowed

to last longer than three or four days. The smell was much stronger

if the hay was cut in hot, wet weather than in hot, dry weather.

If the ferment should last too long, a long iron staff, the end

of which was a cross with a hook, was shoved through to the middle

to take a sample of the center. If the staff when it came out could

have the end held in the bare hand without burning, there was no

danger. If spit made the end of the staff sizzle, then the center

was burning and the hay must be removed. This heat was caused by

layering the hay in the barrack when too wet or having it stapled

in the center too tightly. The outside layer should be tight and

the center less so.

After the first fermentation, the roof was lowered

to adjust to the settling of the hay and a square of hay was cut

out of the bottom for ventilation. After the hay had settled, the

loose strands were pulled out and the sides combed with a "claw" to

smooth them (van Berkhey 1810).

An interesting undated manuscript source in the

papers of the Verplank Family, of Dutchess County, NY, in the New

York Historical Society (Mss. II 40-41) describes how to thatch

and stack a barrack: "Barley or rye straw is best for thatching,

something wheat straw better than barley which is more wooly and

spongying [sic] thus rain more likely to soak through. Grain should

be left on, not flailed off as it would bruise the straw. Rather

a course flax or hemp hatchet [hetchel] should be used. Stacking:

hay not to be stacked wet or packed too lightly because it secretes

a watery liquid because of its natural fermentation which might

result in spontaneous combustion."

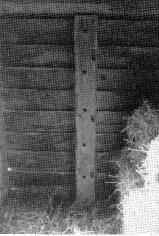

<-

A hay barrack pole, center, reused as part of the framing in

an addition to the Vander Zee barn in So. Bethlehem, NY. Besides

central peg holes, this pole has mortises along the corner to

support the jack. Photo by Shirley Dunn, July, 1989. <-

A hay barrack pole, center, reused as part of the framing in

an addition to the Vander Zee barn in So. Bethlehem, NY. Besides

central peg holes, this pole has mortises along the corner to

support the jack. Photo by Shirley Dunn, July, 1989.

The account contains information similar to that in van Berkhey

(1811), indicating that method was not all derived from local knowledge.

The Verplank treatise did recommend that in making a wheat or barley

stack, the ears of the sheaves should be laid uppermost to keep

the middle of the stack full, or else the rain would run into the

ears and damage them.

Illustrations of Netherlands farms dating from the 16th to 18th

centuries indicate that one, two or three barracks per farm was

the common distribution and that they were located quite close

to the barn. In New York and New Jersey these numbers appear to

have been duplicated. In the Van Rensselaer Bowier manuscripts,

of 11 farm leases, all but one mention "barracks"

in the plural (Van Laer 1908:752-775).

The French diplomat and farmer de Crevecoeur (1925:142), speaking

of his own experience as a farmer in New York in the 1770s, mentions: ".

. . many farmers have several barracks in their barnyards where

they put their superfluous hay and straw". Statements by 20th

century farmers in New Jersey confirm that they (in their 70's

in 1977) remembered "when every farm in their respective neighborhoods

had two or three barracks"

(McTernan 1978:68). Of the nine standing in New Jersey in 1977

only one appeared to be by itself in a field; the rest appear to

have been close to or in the farm yard.

<-

Screw jack on barracks pole. Drawing by Roderic Blackburn, 1989,

after van Berkhey. <-

Screw jack on barracks pole. Drawing by Roderic Blackburn, 1989,

after van Berkhey.

Barracks also occurred in towns, where they presented a fire hazard.

A 1657 New Amsterdam ordinance decreed that "all Thatched

roofs and wooden chimneys, Hay-ricks and Haystacks within this

City be broken up and removed" because of the danger of fire.

Indeed the Costello Plan which depicts New Amsterdam in 1660

shows only one barrack and it is outside the city wall.

The range of crops reported stored in a barrack include the following:

rye and wheat (1632, Manhattan. Van Laer 1908: 192-3), barley (1651.

NYHM Dutch Vol. III p.273), wheat (1769, Ulster County. Anjou 1908:167),

and straw (1770s. de Crevecoeur 1925:142), in addition to hay.

The hay barrack was a familiar adjunct to the Dutch barn and

a useful storage structure on the farmstead. Its cultural ties

were to Northern Europe; it was transported to the New World as

part of the grain centered agrarian culture of the earliest European

settlers of the Hudson Valley and New Jersey. Its continued utility

is evident by its construction through the 19th century, long after

other Dutch-influenced structures were no longer being built.

The vernacular hay barrack should be included in any study of the

agrarian culture which centered on the Dutch barn.

Roderic H. Blackburn is a Senior Research Fellow

at the New York State Museum. His most recent book is Remembrance

of Patria, based on a 1986 exhibit on the Dutch at the Albany

Institute of History and Art.

Shirley Dunn is first President of the Dutch

Barn Preservation Society and Editor of the Newsletter.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Cheap and Easily Made Barracks" in American

Agriculturalist. June 1879 p.222. Describes construction

of a 4-pole 20' high, 16' on center barrack.

Anjou, Gustave, ed. Ulster County Wills II.

Kingston: Gustav Anjou, 1908.

Benson, Adolph B. Peter Kalm's Travels in

North America. Dover Press: New York, 1966. 1749-50 descriptions

of barracks in New York and Pennsylvania.

Buys, L. Brandt. De landelijke bouwkunst in

Hollands Noorderkwartier, Stichting Historisch Boederij-onderzoek.

Arnhem, 1974.

Coventry, Alexander. Memoirs of an Emigrant,

the Journal of Alexander Coventry, M.D., Unpublished account

written during the period 17831831. Albany Institute of History

and Art and New York State Archives.

de Crevecoeur, St. John. Sketches of Eighteenth

Century America, More 'Letters from an American Farmer'.

New Haven, 1925.

McTernan, Don. "Some Surviving Examples of

'Barracks' in New Jersey", in Pioneer America,

January 1976, p.9. Photos of two barracks at Van Ness Farm, Towaco,

NJ, and close up of roof/post connection.

McTernan, Don. "The Barrack, A Relect Feature

on the North American Cultural landscape" in Pioneer

America Society Transactions, 1978 pp.57-69. Discusses and

illustrates eight surviving barracks in northern New Jersey.

Schmidt, Herbert G. Rural Hunterdon: An Agricultural

History. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1945.

van Berkhey, J. le Francq. Natuurlijke Historie

van Holland.Leiden: P.H. Trapp, 1810, Vol. IX, Part 1.

(See pp. 228-234.)

Van Laer, A.J.F, ed. Van Rensselaer-BowierManuscripts.

Albany, 1908.

Van laer, A.J.F, ed. Register of the Provincial

Secretary, 1638-42, Vol. II.

Van Laer, A.J.F, ed. New York Historical Manuscripts

Dutch, Vol. II, III, 1648-60.

Verplank Family Papers, New York Historical Society,

Mss. II 40-41.

Wetenbaker, Thomas Jefferson. The Foundation

of American Civilization: the Middle Colonies. New York,

1938.

An Interview By Rod Blackburn

With barracks nearly all gone, and those surviving not being

used for their original purposes, it would appear that first-hand

knowledge of their structure and function would have died out.

To my surprise this is not quite the case even in New York where,

through the kindness of Vince Schaefer, I came to meet Sam Van

Orden who still farms on land which has been in his family since

1718, on Emboght Bay just south of the village of Catskill in

Greene County, NY. A man of perhaps 70 and still actively farming

with his son, he retains a remarkably clear memory of farming

structures and practices as well as a recollection of what his

grandfather (born in the 1840s) told him about life on the farm.

Here are portions transcribed from a tape-recorded conversation

with Sam Van Orden and his wife on March 19, 1989. Mr. Van Orden

explained that he had worked on a farm where there once was a

hay barrack and these are his recollections of it. Notes in brackets

are by the interviewer.

Mr. Van Orden: The barrack was out there in the field

in the middle of the farm. I combined grain in there. . . about

1947-48. They sold it in the '50s and never used it after that.

. . and so finally the barrack must have fallen down or they knocked

it down. The hay barrack was on the Herbert Moon farm called the

Overbaugh farm or the Fyke farm. The latter was the name given

it as it rested in a small valley in the shape of a fyke fish net

[long cone. See it named in 1867 Atlas of Greene Co.] This was

in the late 1940s, 1947-48. I was combining for him, and they were

using it then for hay. He sold the farm to other people in the

early 1950s. He . . . kept a jug of hard cider under the shade

of the scaffold that was set up at one end of the hay barrack.

He was not up to using modern machinery like the hay baler so he

was the last person in the area to take in hay by hand with a rick.

The barrack was about 30' long and 20' wide with big poles, as

much as 16-18" in diameter. They were of chestnut which was

used for that sort of thing as it is straight, easy to work and

lasted pretty near forever. The four posts were about 25' high

each and they must have been in the ground 4 or 5 feet. Holes were

bored in the post so that they put in a %" pipe to hold up

the roof. The holes were about an inch in diameter and they came

down about half way. There were about three holes in each pole,

so they were about 4 feet apart or more. They used tegles [tackles,

as in block and tackle] on each corner to raise the roof. These

were hooked to a ring in the top of each pole. The roof was a pitched

roof about 8 feet higher at center, quite steep. It had cedar shingles

laid on hemlock boards. They used hemlock boards as they were the

best for holding nails, for the wind would not blow the shingles

off. Those were rough sawn from the log and laid with spaces between

because you want the air to get to the shingles to dry them, less

they rot out pretty soon. They wouldn't use metal for the roof

because when you hoisted the roof you racked it some and the roof

had to give, which shingles will. The rafters were chestnut. I

think the plates were of oak about 4 x 7/8 inches wide with the

rafters, which were poles, cut to rest on the top of the plate

and probably spiked down. The ends of the rafters were butted together,

no ridge pole. The ends of the plates were overlapped [lap joint,

flush] and probably spiked, maybe pinned.

The corner posts were on the outside of the plate and just to

one side of the corner. The plate was held to the post by an iron

strap which went around the pole. The holes in the pole were across

so that the pipe would support both ends of the plates. They started

by placing hay in the East [or short end of this rectangular barrack]

end of the barrack. There was at the end a 4-pole scaffold about

4' x 7' with boards across and from this they could pitch hay up

to the higher levels. One man would be on the wagon, another on

the scaffold to accept the hay and two others on the mow in the

barrack to move it along to the other end. They laid the hay in

there just as you would on the wagon: same as you stack hay. You

lay it around and keep stomp'n it and always keep your outside

a little higher than the middle, you throw some in the middle to

bind your outside fast [so it wo'uld not slip out from you]. You

lay it around like in rows around in a circle. You wanted to lay

it down a hill; most people would think you would lay it up a hill

but no, so it wouldn't slide off. The first cutting of hay he filled

into the barn. He would fill the barn first. Then usually in the

second cutting, which was towards fall and greener, they would

put that in the hay barrack where it would dry right out a lot

better then in the barn. You had a lot of air. Also if the hay

got wet, a little bit soggy and you didn't want to put it in the

barn you could put a couple loads of it in the barrack. It would

dry right out in a few days as the air would circulate right through

there. It is not tight like a barn.

I think one of the purposes of the hay barrack was to take care

of green hay. Originally on that farm and other farms they didn't

keep more than four or five cows, they sold their hay. It was their

main crop to sell. This farm and other farms in this area would

have a barn in the center of the farm somewhere to put your hay

in so you didn't have to go so far. And then they would press it

out in winter and then haul it into town and then they would ship

it on the hay barges. I imagine they originally cut the hay out

of the hay barrack to sell.

Mrs. Van Orden: That was a big business here in the

1800s. The large dairies are from after the second war.

Mr. Van Orden: Most of the main income before the war

was grain but mostly hay.

Mrs. Van Orden: That was the way it was way back. Every

little town was shipping hay.

How do you pitch hay so far up in a hay barrack that is at least

25' high?

Mr. Van Orden: What I remember seeing people do in a

Dutch barn was to bring a wagon in and pitch up half the load then

bring in another wagon full and standing on the full wagon they

would pitch up to it and then another fellow would pitch that up

into the mow, then of course pitch the full wagon down to half

full, and then repeat the operation with another full wagon. So

they would use the wagon as a scaffold. Could do the same with

a Barrack.

[Looking at a photo of New Jersey barracks with poles inside

the roof corners]

Mr. Van Orden: I was wondering if the rain would run

down around your poles a lot and then down into your hay. You could

get spoilage around them poles in the hay. I was not there when

they took the hay out [from the Fyke farm barrack] so I don't know.

On that barrack [Fyke farm] the plate for the roof was inside the

pole with an iron band around the pole on the outside to keep it

tight to the pole. The band was about 3/1 wide. It was back a little

bit from the corner. I don't know if that was the way it was originally.

How did they lay up hay in a barrack?

Mr. Van Orden: If you put in hay that is like that, that

is too green -If you put that in you can get mow burn, it gets

all white, not good for the animals.

When you lay in hay you put it in around the outside edge and

stomp that down and in the middle, same as in a mow, you just throw

hay in the middle and you don't stomp that down, depending on the

hay. If it is dry you can stomp it, but if it is a little bit green

then you don't stomp. it, and that is when they put the salt on

to it. You wanted the air to work into it.

[Quote says you cut a hole into the middle]. You can cut that

out with a hay knife. [shows me one].

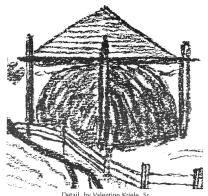

Valentine

Kriele, Sr., sketched this farm scene showing a hay barrack in

the 1950's. He lived at Purling, near Cairo, Greene County, NY.

See also detail of a second scene, below. Courtesy Shelby Kriele

and Valentine Kriele III. Valentine

Kriele, Sr., sketched this farm scene showing a hay barrack in

the 1950's. He lived at Purling, near Cairo, Greene County, NY.

See also detail of a second scene, below. Courtesy Shelby Kriele

and Valentine Kriele III.

Detail, by Valentine Kreile, Sr ->.

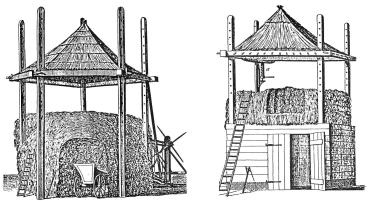

Five-pole hay barrack (left), published

in van Berkhey, 1810 (Vol. IX). The Dutch wagon size suggests

this barrack is about 24' wide and 33' high. Note the winding

jack set in position to raise the roof using a long pole. Its

form is similar to that of a cheese press. Its relative size,

however, appears exaggerated for clarity. Four-pole barrack at

right, also from van Berkhey.

RESEARCH

FIND

|