|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

Newsletter,

FALL 1990, Vol. 3, Issue 2

The

Plank Roof:

met planken

bequaem decken

By Shirley Dunn

Planks were a once-popular roofing material for houses,

barns and sheds on early Hudson Valley homesteads. Use of this

roofing is now nearly forgotten, but, occasionally, surviving plank

roofs can still be found under later roofs or sheltered by additions.

For example, plank roofs have recently been identified on some

Schenectady and Albany County Dutch barns. The Teller Barn of Schenectady

had a plank roof when it was taken down some forty years ago. In

addition, plank roofs remain in place on an early house in Schenectady

and on one in Schodack, NY.

While undoubtedly they may remain on other structures, such roofs

usually go unrecognized because they are covered with later materials

and, most importantly, because the type has been forgotten. Present

day owners may assume that the carefully fitted boards above the

rafters on old houses or barns are merely old roof boards when,

in fact, they once were the roof itself. For the same reason, references

to plank roofs in early housing contracts and other documents have

been overlooked or misunderstood.

Plank roofs once were common enough. In upstate New York, plank

roofs were still applied to structures as late as the mid-eighteenth

century. Peter Kalm, a traveling Swedish naturalist who recorded

information about each area he visited, wrote about houses north

of Albany that the "roof was either of boards or shingles.

.. " (Kalm, Travels in North America, Vol. II, Dover,

1966, 612).

A properly beveled and fitted plank roof sheds water and snow

efficiently and was as satisfactory as any other roof covering.

If, after the passage of years, boards split or shrank, the plank

roof made a solid base for wood shingles. While some plank roofs

undoubtedly were intended as temporary expedients, others were

installed with sufficient craftsmanship to survive as the sole

roof covering for many years. One of the best examples survives

on a mid-eighteenth century house near South Schodack, NY. (See

illustrations.)

The plank roof was in use in the Albany area and in other settlement

areas along the seacoast as long ago as the seventeenth century.

Planks and boards were readily available at an early date, particularly

in New Netherland, and were specified in building contracts in

Beverwyck (Albany) and Manhattan documents by the 1640's. Numerous

early saw mills in the Dutch colony processed abundant timber;

consequently, sawn lumber was widely available during the long

land-clearing phase of European settlement

Occasional wooden roofs appear in Netherlands paintings of the

period, although many roofs in the homeland were thatched or tiled.

All three materials, thatch, tile, and wood, were experimented

with here during the first few years of Dutch settlement in New

Netherland. At first, thatched roofs covered many area structures

as they did on the continent However, the harsher climate and limited

materials (straw was substituted for reeds) in New Netherland did

not encourage the continued use of thatch. In addition, thatched

roofs were recognized as fire hazards, especially in cities.

To substitute for thatch, a householder might choose pantiles,

planks, or shingles. In America, as overseas, pantiles, while often

the preferred roofing, proved, I believe, more expensive than other

coverings. Moreover, loads of tiles were probably difficult to

transport due to weight and fragility. Consequently, tiles emerged

as a prestigious roofing limited, in the main, to public buildings

and city residences of substance. White pine or cedar shingles

were known to the Dutch and their English successors, but, as a

product of intensive hand labor, they also were expensive. It is

my opinion that shingles were not used very widely here in the

seventeenth century because mention of shingles is rare in early

Hudson Valley building contracts.

Therefore, for utility buildings such as barns, and for housing

stock when pantiles could not be obtained, planks were a popular

and culturally acceptable roofing material, one already familiar

to the Dutch community. In addition, from earliest settlement through

the eighteenth century, the abundant sawn materials were reasonably

cheap.

<-Although

now covered, the plank roof on this Dutch-style house near South

Schodack, NY remains visible in the attic of the addition shown

at left. Photo, spring, 1988, by Shirley Dunn. <-Although

now covered, the plank roof on this Dutch-style house near South

Schodack, NY remains visible in the attic of the addition shown

at left. Photo, spring, 1988, by Shirley Dunn.

A plank roof had one more attribute besides availability, cultural

acceptance and economy. Planks on a roof made a building relatively

fire-safe. This attribute of plank roofs was part of the public's

consciousness for many years.

In February, 1656, an impoverished old man, Willem Juriensz,

was unable to remove his dangerous thatched roof in the village

of Beverwyck. His neighbors were called on to make a contribution

to replace Juriensz' condemned

"straw" roof, with one of planks, "in order, thereby,

as far as possible, to prevent all danger of fire." A variety

of individuals contributed for the new roof according to their

concern and ability - Sander Leendertze, 12 planks and eight guilders'

worth of nails; Rutger Jacobs, 5 planks; Andries Herpertz, 8 planks

- and so on, making clear the character of the new and safer plank

roof (Minutes of the Court of Fort Orange and Beverwyck,

Vol. I, p. 238, 255). [Note: the Dutch word "planken" was

verified courtesy of Charles Gehring, translator for the New Netherland

Project]

The feeling that planks were a relatively safe roof may have

contributed to their continued use for houses and barns long into

the eighteenth century, even when pine shingles were readily available.

For example, in the 1740's, when an outbreak of the French and

Indian wars threatened, an Albany blockhouse, an important link

in the stockade around the city, was ordered to be covered with

boards, probably as a protection against flaming brands. The City

Records record the following:

October 26, 1743. This board agreed with Anthony Bratt to remove

the block house near the City Hall to the place where the powder

house stands upon the plain, and to putt it up there, to find

all the materials necessary, to mason the stone of the foundation

above ground with lime, to put a new roof of squared pine boards

thereon, to mason the pipe of the chimney above the house with

lime, and to make draws before the portholes below, and to finish

all compleat ... (Munsell, Annals of Albany, Vol. X,

Albany, 1859, 114.)

Plank roofs were not unique to the Albany area. Seventeenth:century

records from Manhattan mention plank and, occasionally, clapboard

roofs. In 1642, a house built by Thomas Chambers was to be enclosed

all around and covered overhead with clappoards "tight against

the rain." (New York. Historical Manuscripts: Dutch,

Vol. II, 13-14). Near Manhattan in 1649, Symon Root and Renier

Somenson agreed to build two identical houses on which the roof

frame was to be covered with planks (New York Historical Manuscripts:

Dutch, Vol. III, 103). Further up the river, in June 1676,

Claes Jansen agreed to build a house for Dirck Benson at Claverack

(present Columbia County, NY), for which the contractor was to

met plancken bequaem decken, "suitably cover the

roof of the house with planks" (Early Records of Albany,

Notarial Papers 1660-1696, 346). Earlier in 1676, the same

Claes Jansen had contracted to erect a house, probably at Albany,

with a roof of "overlapping planks" for Hans Hendricksen.

This reference is important because it gives a clue to the method

of application of the planks (Early Records of Albany 1660-1696,

471). [Again, Charles Gehring, of the New Netherland Project, has

verified that the Dutch word "planken"

appears in the originals.]

Plank or clapboard roofs were not limited to the Dutch of New

Netherland and could take more than one form. For example, the

mid-seventeenth century Adam Thoroughgood House in Virginia Beach,

Virginia, retains sections of an early clapboard roof under later

roofing. The early roof consisted of horizontal overlapping oak

clapboards about 56 inches long and six inches deep. Both ends

of each clapboard were feathered and they were nailed with two

nails at the overlap of the feathered ends, while one nail secured

the clapboard at midpoint. All nailing occurred on roof rafters.

The extant Brush-Everard House at Williamsburg, Virginia, retains

similar roofing from the eighteenth century, featuring somewhat

longer boards.

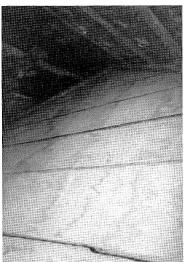

<-Part

of the original plank roof, preserved when an addition was put

on the house shown on page three. No shingles were ever nailed

over these fitted boards. <-Part

of the original plank roof, preserved when an addition was put

on the house shown on page three. No shingles were ever nailed

over these fitted boards.

However, surviving Dutch plank roofs are different from the clapboard

roofs of Virginia. Existing roofs in Schenectady and Schodack contain

wide milled planks laid horizontally in uniform lengths up to ten

or eleven feet. These planks met and were nailed at a seam over

a central roof rafter. The seam and the plank ends probably were

covered by a narrow strip of wood. The lengthwise edges of the

planks were beveled to provide a water-resistant lap over the plank

below. There were no gaps in the original tightly fitted installation.

A common phrase in New Netherland building contracts is

"roof and floor tight," referring to the fitting together

of boards or planks. In contrast, common roof sheathing intended

to support wood shingles consisted of irregular boards which provided

gaps and openings.

Although the custom of roofing houses and barns, including some

Dutch barns, with horizontal fitted planks continued well into

the

eighteenth century, the practice in the upper Hudson area seems

to end after the coming of many New Englanders to the Albany area

in the decades after the end of the French and Indian wars. While

there was less timber in established settlement areas by then,

probably the main reason the roofs went out of fashion before 1800

was a social one - their association with the perceived "old-fashioned" and "inconvenient"

Dutch way of life.

Casual use of boards on roofs of outbuildings probably knows

no time limits. However, carefully crafted plank roofs with a beveled

overlap can be an indicator that a structure predates the end of

the eighteenth century and probably predates the Revolution. The

wooden roof was a familiar sight in the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries. Its utilitarian practicality featuring a material widely

available, fire resistant, and relatively inexpensive, as well

as its cultural acceptability, led to its use on a variety of buildings

in the country and also in the city.

Such roofs when discovered on a Dutch barn or old house should

be preserved as part of the craftsmanship and uniqueness of the

building's architecture. These unusual roofs serve, as well, as

important historical evidence of the, origins and evolution of

the conservative social environment which characterized areas of

North European settlement, the very areas where Dutch barns are

found.

The author, a Trustee and former president

of the Dutch Barn Preservation Society, is Editor of the Newsletter.

The

Dutch Barn Preservation Society

c/o

The Mabee Farm Historic Site

1080 Main St. (Rt. 5S)

Rotterdam

Junction, NY 12150

Site

Phone: (518) 887-5073

DBPS

SITE MAP

Copyright

© 2007. Dutch Barn Preservation Society. All rights reserved.

All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to

use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or

downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced

for distribution, sale, or profit. |