|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

SPRING 1999, Vol. 12, Issue 1, part two

The Restoration

and Reconstruction of the John J. Post Aisled Dutch Barn, 1997-1998,

continued.

The new site would have to be graded, trees felled and stumps

pulled, 16 concrete piers excavated and poured, and a fieldstone

foundation and retaIning wall built. We needed to prepare timbers

for and join four new main posts, eight side wall posts eight side

wall ties, two side wall plates, two purlin plates, new side wall,

cross and main sills and threshing floor joists, four wagon door

posts and all the miscellaneous studding. The rafter poles had

to be peeled, adzed flat and joined. And that was the easy part.

Remember please that all that was left of the purlin plate was

a seven foot section that gave us the location of two sway braces

and two post mortIses, and that we had the ruined carcasses of

the four interior bent columns, to be replaced by columns of comparable,

but not exact, original size, and that all the other purlin braces

had to be made and joined to the new (scarfed) plates. It is sufficient

to say that on raising day the new plates fit the new braces exactly,

as they must, and that all praise is due to Paul Hofle's intellectual

and manual abilities, as he not only plotted the Pythagorean course,

but Joined the braces and timbers as well.

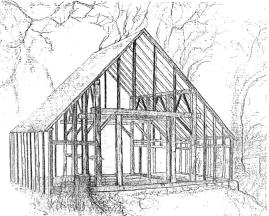

Drawing

of the John J. Post Dutch barn showing structural mambers. Drawing

by Debra Fiacco. Drawing

of the John J. Post Dutch barn showing structural mambers. Drawing

by Debra Fiacco.

The four remaining posts had only marginally survived the culling

that eliminated their brothers, Large sections were excavated and

repaIred with joined repair pieces and epoxy fillers. Repaired

areas were veneered with 3" thick slices of hewn surface.

New post bases were fabricated from sound old stock and joined,

epoxied and bolted to the old fabric. Stainless steel bolts were

bunged with hewn oak rounds The anchor beams were better, two of

the four requiring major work. Bent 2 (from the South) needed a

7 foot section scarfed on, epoxied and through-bolted as well Number

4, North, is about 85 % laminated plywood, joined oak pieces, stainless

steel and veneer. Everything, when done, was soaked in Boracare,

a nontoxic (to humans and animals) boron based insecticide, that

is especially effective on post beetles and carpenter ants.

Jeremiah and B.J., apprentice saints and joiners, spent their

seven months lifting several tons of oak, pine, poplar, granite,

sandstone, dIrt, basalt and concrete, splitting out and shaving

about 500 feet of black locust trunnels, cutting joints (sometImes

the same one three or four times ), mixing several gallons of epoxy,

raising frames and nailing on eighteen hundred board feet of pine

siding and thousands of cedar shakes. New sawn white oak, purchased

oversize, was broad axed or adzed to dimensIon by these two also.

After six weeks of repair, restoration and new work, the frame

members were transported by pickup truck and trailer to the site

in Congers, New York, (village of Clarkstown). The high point of

that journey beIng the four thirty-foot plates carried on the truck's

rack. The white oak and pressure treated SIlls were placed on the

stone foundation walls and bolted to theIr piers. Pipe scaffolding

was erected and bound with chain to the sills, We then rigged timbers

atop the scaffolding and raised the four bents wIth "come

alongs" and muscle. The bents raised and temporarily supported,

we placed the sway braces, tied them up with line, and dropped

the purlin plates in place, and with some very minor adjusting,

they were fastened off with new locust pins.

The side walls and their plates, posts and studs were raised,

ties installed, and diagonal braces let in. The 22 rafters were

lifted into place, after being joined on the ground. Skip sheathing,

free edged, was stripped of bark, cut to length and installed.

The 1 "x12" eastern white pine planking was installed

with 1 0 penny cut nails, and the 24"

red cedar hand split shakes were nailed on by hand, 33 squares

in all. It sounds so easy. The procedures described above took

seven weeks, and we often saw the sun rise and set at the damn

barn.

With the building raised, roofed and sheathed, we began the construction

of the four wagon and four aisle doors, beaded and clench nailed

with wrought strap hinges, the four south wagon door hinges being

original and the rest salvaged from area barns and vetted for date.

We took our tulip-poplar boles to Matt Beckerle's band saw mill,

where he cut our threshing floor planks for next to nothing as

a contribution to the cause. One of these trees belonged to a Mr.

Kellog, who had planted it himself 45 years ago, to have it blown

down in a May windstorm. The tulip poplars hereabouts are often

60 feet or more to the first branch and 3 to 4 feet in diameter,

yielding clear wood in 18 to 25 foot planks. The Wortendyke (Dutch)

barn in Pascack (now Park Ridge), New jersey is framed completely

in this material, as are most of our Dutch houses' exposed joists.

The barn was finished in October, six months after we started

collecting materials. We trained two apprentices and introduced

about 30 people to the traditional methods of wood working and

framing, learned much that was new about the restoration and preservation

of old material, and raised a Dutch barn in Rockland County for

the first time in nearly two hundred years. There were times when

the only sounds at the homestead were of broadaxes and chisels

and birds, and the voices of the joiners. When one stands inside

the barn now, on a sunny day, doors shut, the light emanates from

the seams and vents and illuminates the interior with rays and

beams and sprays of light. The main timbers, washed and cared for,

glow, and their tree-like structure of braces and plates is wonderfully

explicit. The visitor stands on an expanse of wide aromatic planks,

gazing up at the astonishingly complex patterns of rafters, sheathing

and shakes. It was worth all the effort. The John J. Post barn

and the Schueler/Paul house will be open in June 1999.

Foot notes and bibliography

1. Van Tienhoven Purchase, June 15, 1696 Calendar

of New York Colonial Manuscripts, Indorsed Land Papers in the Office

of the Secretary of State of New York 1643 1803, 11, 222.

2. A History of the Post-Sterbenz Land, Hugh Goodman.,

pgs.1-9 Letter from Greg Huber "Post-Sterbenz True Form

Dutch Barn".

George Turrell, a former trustee of the DBPS,

is the Proprietor of AchterCol, a historic restoration firm

in Piermont, New York. Since 1986, AchterCol has restored historic

buildings and artifacts, concentrating on Dutch-American barns

and houses.

The JJ.Post barn restoration was (3/18/99)

awarded the Historical Society of Rockland's 1999 Preservation/Restoration

Category Citation.

The Technical Description:

A

four-bent, three-bay aisled Dutch barn, 36 feet x 30

feet (width by length), side walls of 9 1/2 feet east

and 10 feet west, peak of 24 feet, nave of 18 feet width,

single transverse aisle ties, anchor beams of 12" x

1.0 1/2" with 6" to 8"

wedge less tenon extensions, anchor beam mortise square

shouldered, anchor beam scribe marks at 2% verdiepinghs

at 48" above anchor beam, anchor beams of white oak

(3) and red oak (1) main columns of 9" x 7" X

16' 6". The barn is without raising holes or manger

dadoes, with the longitudinal struts let in on threshing

floor side (east) and aisle side (west) primarily of white

oak with one chestnut and One red oak. Purl in plates of

6" x 5"

hewn oak, 30 feet in length, side wall plates ditto, sawn

purlin and anchor beam braces, no marriage marks except

at purlin braces. Side walls had no diagonal bracing, except

at the comer posts where let-in dovetail braces ran from

post to plate. Hewn surfaces were broad-axed to finish

size, rafters adzed flat on one side, except at gable ends

where two sides were flattened, Rafters were hewn poles

of white ash, tulip poplar, white oak and red oak, joined

with a trunneled, lapped joint. Trunnels of white oak,

1" diameter, 11/2" diameter at anchor beam/post

connection One section of a manger base was extant, used

as an aIsle tie. As Greg Huber points out In hIs report

on the barn, the mixture of techniques and procedures observed

above led him to place its construction In the first part

of the nineteenth century, The county tax records of 1812

confirms this, as the barn was listed as a ratable of John

J. Post. |

Dutch Barn or Not?

The

Dutch Barn Preservation Society continues to search for articles

to feature in the newsletter. If you have an article or would like

to write an article regarding Dutch barns or houses please contact

the editor. The barn above is the Crounse-Van Aernum Dutch barn

in Guilderland, Albany County, New York. The roof was replaced

in 1959 after a wind storm blew off the original. Photo courtesy

of Chris Albright. The

Dutch Barn Preservation Society continues to search for articles

to feature in the newsletter. If you have an article or would like

to write an article regarding Dutch barns or houses please contact

the editor. The barn above is the Crounse-Van Aernum Dutch barn

in Guilderland, Albany County, New York. The roof was replaced

in 1959 after a wind storm blew off the original. Photo courtesy

of Chris Albright.

The Wortendyke Barn Museum

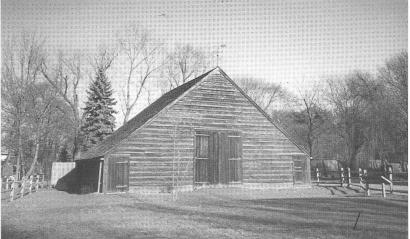

A recent picture of the Wortendyke barn. Notice

the very low side walls. All photos by Robert L. Cohen.

By Robert L. Cohen, Curator, Wortendyke Barn Museum

The Wortendyke New World Dutch Barn is located in the lower Hudson

Valley approximately five miles south of Tappan, New York and approximately

seven miles north of Hackensack, New Jersey. It is also about five

miles west of the Hudson River in northeastern Bergen County which,

at the time of the Revolutionary War, extended from the Hudson

River all the way to Sussex County in the west. Bergen County included

present day Bergen, Hudson, Passaic, and part of Essex Counties.

In those early days of what I'll refer to as the "Hackensack

Valley", Bergen was primarily a farming area that was settled

in the mid to late 1600's by mostly Dutch with some German, French

Huguenot, and a mixture of other European stock. The Dutch were

the largest landowners in Bergen County and their farming activities

spread along the Hackensack and Passaic Rivers in northern New

jersey and to the Raritan and Millstone Rivers in central New jersey.

Remember, before 1664 the entire region from west of the Connecticut

River to the Delaware River and including the Hudson, Mohawk and

Schoharie River Valleys (in present day New York State) were part

of New Netherlands and controlled by the Dutch West India Company.

Boundaries between Colonies really were non-existent until the

late seventeenth to late-middle eighteenth centuries. The population

of the entire state of New jersey in 1745, just before the Wortendyke

Barn was built, was estimated at 61,000. Bergen County probably

had about 67,000 inhabitants in 1770.

Bergen County in the 1770's could be described as having "rich

and broad farmlands...abundantly watered (and) populated by prosperous

farmers descended from the original settlers of New Netherland.

From all accounts, the Hackensack Valley was delightful and prized

farm country with handsome houses, active mills and barns and yards

brimming with livestock and grain." Most of the people living

in the Hackensack Valley at the time the Wortendyke was raised

(circa 1770) were independent farmers owning farmland from 75 acres

to the hundreds of acres. People of Dutch ancestry were numerous

in the Hackensack Valley. They doggedly spoke Dutch in their homes

and churches and kept their Old World customs even though Holland

surrendered New Netherland to the English a century prior to the

American Revolution. "The Dutch were among the largest landowners

in Bergen County..."

Records show Frederick Wortendyke, Sr. having moved from New

York City to Tappan and then to the Hackensack Valley where he

purchased some 465 acres of fertile farmland from Hendrick Vanelinda

in 1735 in what is present day Woodcliff Lake and Park Ridge, New

jersey. The Wortendyke homestead is directly across from the barn

and is dated from about the 1750's, which means the house had stood

about 20 years before the Wortendyke Barn was built. This could

have been done for a number of reasons including building a bigger

and better barn for more storage space. The homestead was originally

one floor built with red sandstone. This was the most prevalent

building material in the area, rather easy to to find and used

to build many fine Dutch Colonial homesteads. Many have beautifully

withstood the test of time and are still standing as well deserved

historic landmarks throughout Bergen and Passaic Counties. Familiar

names adorn the historic markers: Zabriski, Demarest, Blaunelt,

Ackerman, Goetchius, Hoper, Haring, Van Wagoner and Wortendyke,

etc. These houses are the legacy of not only the early farmers

of northern New Jersey, but as described to the author at the Ackerman

family reunion in 1998, the "pioneers" in a New World.

They found-it is true-fertile land, but also Native Americans,

forests which needed clearing and wild animals. Plus all their

buildings were hand made with hand made tools and built with the

help of animals. Horses and oxen were used to help clear the land

and with building. The Dutch used both, but as time evolved seemed

to favor the horse over the ox.

The barn was used by the Wortendyke family for farming purposes

until 1851 when it was sold. The early Dutch farmers tended to

have large families and left shares of the farm to all the children

including daughters. The land had been farmed continuously by the

Wortendykes for one hundred and fifteen years, from 1735 to 1851.

The land and barn were sold several times after 1851, but the barn

remained in use as a barn until well into the 20th century. By

the 1950's the barn was being used for storage when it was purchased

by an artist and sculptor who converted the barn into an office

and studio. After selling some of the acreage to developers he

sold the barn to Bergen County. From about 1960 until the mid 1980's,

the Pascack Historic Society was showing the barn by appointment.

In 1997, Bergen County turned the restored barn into the Wortendyke

Barn Museum. It is open from mid May to mid-October and by appointment.

The Museum is located on 13 Pascack Road, Park Ridge, New Jersey

and being a National Historic Site is well maintained and curated

for visitors. Exhibits include handmade 18th and 19th century farm

tools and implements.

There are outdoor exhibits which give some background on the

Wortendykes and the Dutch settlement of the Hudson Valley. The

museum also touches on the effects of the American Revolution on

the area.

For more information on the exhibit/directions

to the barn, or hours of operation, call the Division of Cultural

and Historic Affairs at (201) 646-2780, Monday through Friday

9 a.m. until 4:30 p.m.

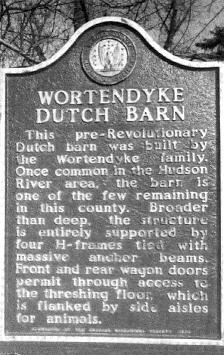

Historical

marker at the barn site. Historical

marker at the barn site.

Author standing in wagon door entrance performing

curator duties.

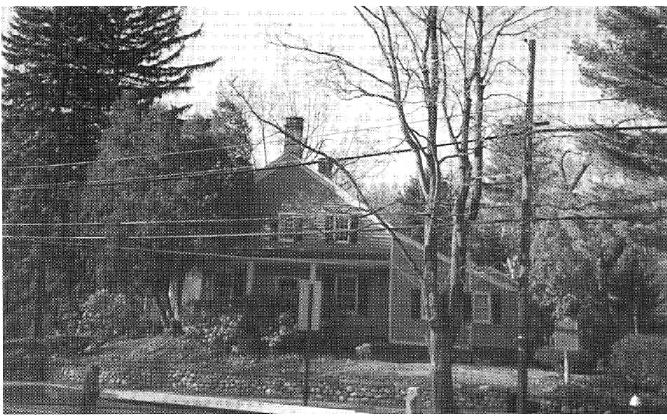

Wortendyke House standing across the street from

Dutch Barn, circa 1750. Roof has been raised and knee wall added

to original red sanstone structure. This house is also a Bergen

County Historic site.

|