|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER

FALL 2000, Vol. 13, Issue 2

DUTCH BARN PRESERVATION SOCIETY

NEWSLETTER

RAISING

HOLES IN EAST GELDERLAND, THE NETHERLANDS

Introduction

by Karen Gross

In a letter of June 1998, Dr. Ellen van Olst, Director of the Stichting

Historisch Boerderij Onderzoek (Institute for Historical

Farms Research) wrote: "raising holes are indeed known in

the Netherlands, although we have not (as yet) done any serious

research into this matter."

The only information up to now has come from the easternmost part

of the country, i.e., the area between Arnhem and the German border.

[Because anchor-beam construction is prevalent there, the area

is particularly relevant for Dutch barns.]

Dr. van Olst reported that her research staff have never noticed

any raising holes in other parts of the country. She believes that

this does not mean that there aren't any, just that no one has

taken any notice of them: "However, it is a subject which

will get more attention in future, thanks to your letter." (Of

course, thanks to Peter Sinclair's letter to me.) One of the questions

they hope to answer is whether raising holes are only found on

frames that were light enough to be raised completely by hand.

This was the case in the southern and eastern Netherlands where

native oak with a relatively small cross section was the rule.

In the west and north, imported pine was used almost exclusively

after 1600. The size of those timbers made the use of block and

tackle necessary.

Dr. van Olst sent an excerpt from one of the institute's publications

which deals with farm buildings in the province of East Gelderland

from the turn of the century until the 1940s. The book is an example

of the growing interest in all aspects of timber framing, especially

in regional variations. Chapter 5 deals with raising bents. There

are no descriptions of the buildings, but the drawings show anchor-beam

construction with a verdiepung similar to those in American

Dutch barns. There are indications that the barn and the living

quarters are under one roof. In a letter of August 8, 1998, Dr.

van Olst confirmed that this was the case until well after the

Second World War. She wrote that even in areas where there was

no vernacular tradition for Hallenhauser, people and animals

are still housed under one roof on modern Dutch farms. The only

exception is in parts of the province of Zeeland where houses and

barns were in separate buildings from the 18th century on.(1)

Dr. van Olst says that in the eastern parts of the country, the

entire building, both house and barn, was originally timber-framed

[similar to the Hallenhaus on the Westmunsterland Farm].

Beginning around 1850, increased prosperity and the availability

of cheap bricks led to the original timber structures being replaced

by bricks, although many of the original bents were retained. By

the end of the century, Hallenhauser were still being built,

but the dwelling area was completely of brick and a sol id wall

separated the barn from the house. The traditional timber frame

was retained in the barn, however. These are the timber frames

that the carpenters in East Gelderland remembered so vividly -

preparing the timbers and cutting the joints, assembling them and

raising them. The author of De vakleu en et vak, L. A. van

Prooije, has recorded their memories of the methods and equipment

used for raising and the dangers involved.(2)

Dr. van Gist mentioned that the 1997 reprint is still available

from the Stich tung Historisch Boerderij Onderzoek. There

are other publications on their list that may be of interest to

readers.

Descriptions of raising a frame are extremely rare. To my knowledge

there are no records available in Dutch or German on raising timber

frames prior to the 20th century. For one thing, these were quite

literally "trade secrets". Methods of construction were

passed on from generation to generation by showing and telling.

Obviously, outsiders would have seen a building being erected,

but apparently did not think it worth writing about and would not

have noticed the details in any case. 19th and early 20th century

treatises on timber framing deal primarily with design and decoration,

not with construction. Those that mention -craftsmanship at all

show the timbers being cut to size and assembled but not being

erected. Contemporary books and manuals for carpenters were full

of detailed drawings showing a great variety of joinery and frames

for all kinds of buildings, but there is no indication of how the

frames were raised.(3)

In a resume of the research done on historical buildings in the

northeastern Ardennes/Belgium] and the Hohes Verin/Germany

(to the south of Gelderland], Frank Simons reports that with the

exception of the well known architectural historian Gerhard Eitzen

almost no one has given serious thought to the connection between

the way the frames were raised

and the joinery. Although Eitzen began publishing in the 1950s,

there is almost no information available on this aspect of timber

framing for that particular area [eastern Belgium and western Germany].(4)

De vakleu en et yak(5)

Chapter 5: The raising of the bents and the "raising meal"

This chapter is based on oral history. The author interviewed carpenters

that had lived and worked in East Gelderland about all aspects

of timber framing, but he found that what they were really eager

to talk about was raising the bents. Chapter 5 deals with the preparations

for the raising, the dangers involved, the short prayers to ward

off misfortune, the various devices used to raise the bents and

the actual raising. It concludes with the festive meal shared with

all the helpers.(6)

The drawings show bents with traditional anchorbeams and verdieping although

some architectural historians think that this "old-fashioned"

construction had been replaced by the more progressive and efficient

tie-beam construction long ago. The kinds of buildings being raised

are not mentioned specifically, but there are indications that

they were for a Hallenhaus. The partition separating the keuken/kitchen

from the deel/threshing floor is mentioned twice - once

when the bents are being placed in position for raising and again

when the bent nearest the partition had been raised. The frames

have no sills; the bents are placed on piers a few inches off the

ground.

The previous chapter dealt with cutting the joints and assembling

the frame. This was done as close to the new farm building as possible,

so that the heavy bents wouldn't have to be carried any further

then necessary. Prior to the raising, the bents were laid out in

the proper order. First the bent for the back of the building was

laid flat on the ground, close to where it would eventually stand.

Then each of the subsequent bents were stacked on the others until

the one nearest the partition separating the deel from the keuken was

at the top of the stack. In Vorden (7), this was called the veurhuusgebint.(8)

Now the raising could begin.

Dangers involved in raising the bents

As at any traditional barn raising, the craftsmen were assisted

by men from the neighboring farms. The neighbours had been "craning

their necks looking out for this day"(9) for some time. They

would be compensated for the hard work by the richtemaoltje,

the "raising meal", and by the good fellowship and fun.

However, the carpenters reported that inexperienced assistants

were sometimes more of a hindrance than a help. Sometimes the farmers

didn't follow instructions, sometimes they played silly pranks

and sometimes they were so frightened that they didn't pull their

own weight. One of the carpenters said that they were not afraid

of horses and bulls, but terrified of bents. Lives were endangered

by their unprofessional behavior and horseplay.

Even without inexperienced helpers, raising the heavy bents was

dangerous enough. A carpenter from Vragender talked about a close

call he had had when a bent fell over and one from Toldijk told

about his old master who had both legs broken when a bent fell

on him. The oral witnesses from Almen and Oolde could remember

well that people had been injured or killed by falling bents. To

ward off such accidents, there was usually a short prayer before

the raising began. A carpenter from Breedenbroek said that in the

Catholic enclave of Spork, close to the German border near Dinxperlo,

the carpenters always said the Lord's Prayer before they started

work. In Zieuwent they said the Lord's Prayer and a Hail, Mary.

A Protestant carpenter from Lichtenvoorde said that before the

raising began, some one shouted "Quiet!" and everyone

prayed silently for the success of the venture.

Equipment used for raising the bents

<-

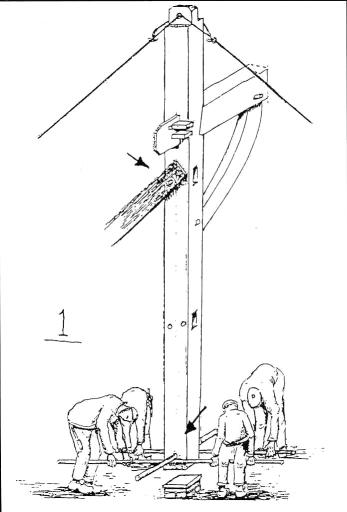

Drawing One. <-

Drawing One.

The interviewer asked what kind of equipment was used to raise

the bents. The very first thing mentioned was a hole [gat]

in the upper part of the post [gebintstijl]. Usually the

hole was bored specially, but sometimes the holes for the trenails

[toogpinnen] that would later secure the girts [Spreibander]

were used as raising holes [richtgat]. In either case, the

hole had to be all the way through the post, parallel to the beam

[gebintbalk] i.e. from the outside of the frame to the inside,

just as they are on the Dutch barns.

A big bolt [dikke bout or boltn] was used to attach a long

piece of wood to the outside of the post. [See drawing 1.] The

bolt was held in place on the inside of the post by a nut and washer

[en moere en plate]. There are many names for this piece

of wood: volg, volger; volgrieje, volghout, vaankroewe, slepholt,

zwerpe, schore, slaope, or andrukker. This piece of

wood was used to push the bent upright as well as to secure it

after it stood in place, i.e. both as a raising pole and a temporary

brace. [KG As far as I know, there is no one word for this in English,

so I will use the same Dutch word that the article uses: volger.]

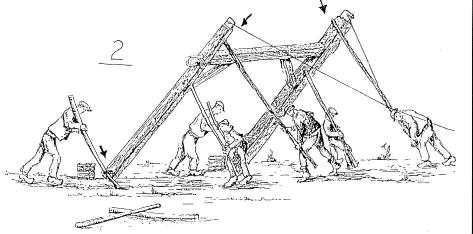

-> Drawing Two

This was not the only way to fasten a volger to a bent.

Some carpenters used the same kind of nail they used for bents

and sawhorses (described in chapters 1 and 4) instead of a bolt.

If the nail was made especially for volgers, it was called

a volgpen in Varsseveld. In Ruurlo, the nail had a broad

head at one end and a slot for a tiny lock at the other so that

the volger couldn't slip out.

As a matter of fact, the author says he found that almost every

carpenter had a different method, doubtless a result of tradition

and personal preference. If only one pair of volgers was

used, there was always the danger that the bent would be pushed

too far and tip over backwards. To prevent this, one man standing

on the same side of the bent as the volgers, held tight

to a rope tied around the beam to keep it straight once the bent

was upright. In Vragenden a strap was first used to help raise

the bent and then to keep it upright. The "strap-puller" [touwtrekker]

simply ran back and forth under the bent.

Sometimes more than one pair of volgers were used. Some

carpenters preferred to use short ones to start shoving the bents

up and then use them as temporary braces while they changed to

longer ones. Others used two pairs of long volgers, one

on each side of the bent to push and pull and then to shore the

bent up after it was plumb. Drawing 2 shows two pair of volgers on

the same side of the bent being used to push. Some carpenters said

that they never used round poles for volgers, others said

that they always did because they were easier to grip than a flat

plank.

There was another way to use the volgers without fastening

them to the bent at all. The carpenters tied them together in an "X"

with a piece of rope; the top of the "X" was shorter

than the bottom. The beam was laid in the upper "V" and

pushed up. Because the bent could easily be pushed too far and

tip over, one or two men holding fast to a rope or chain had to

stand on the same side of the bent. As soon as the bent was upright,

they held it in position.

Long poles were also used. A carpenter from Mairenvelde called

them raising poles [steigermasten] but others called these

volgers as well. These were tied to the beam or the posts with

a rope. A carpenter from Kottense said "You have to tie them

around the beam." ["Dee mos ie um den balk hen strieken

(strikken)."] There was a hole in the top of the pole

to put the rope through. The rope was first looped around the beam

and then the pole was shoved through the loop and twisted until

the rope was tight. The same carpenter from Kottense said that

these poles were about a meter longer than the height of the beam.

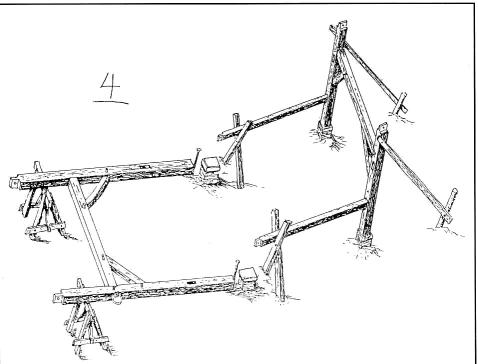

In addition to volgers, poles, ropes, chains or straps,

other equipment was occasionally used. A bent could be laid on

one or two sawhorses [bukke or schraangs] to get

the top off the ground. Then the top was lifted and the sawhorse

shoved further and further under it. [See drawing 4.] A carpenter

from Gelselaar said that sometimes the undercarriage of a wagon

was used in the same way; a carpenter from Varselder used a cart.

In some places, ladders were used to push the bents up. The legs

of the ladder were placed on either side of the beam, so that the

beam lay on one of the rungs.

In order to raise the bent safely, some carpenters used the holes

bored through the tenons at the tops of the posts as well. A drawing

shows ropes threaded through them to hold the bent so it won't

tip over. [See drawing 1.] Others bored holes through the bottoms

of the posts. An iron rod long enough to extend on both sides of

the post was pushed through the hole parallel to the beam. During

the raising a thick piece of wood or a crowbar [knuppel or haevel)

was placed under the pin with one end stuck in the ground and the

other on a man's shoulder. These men made sure that the posts stayed

on the ground and didn't slip. (See drawing 2.)

The actual raising

When the actual raising began, the local farmers as well as

the masons and others who had worked on the building came to help.

The carpenter who was responsible for the job gave the orders.

Sometimes he stood to one side so that he could see how the raising

was going and called: "Heave ho, steady, boys" or "Push

it up." or "Pull it back."

A plumb line was used to see when the bent was absolutely perpendicular.

In Beltrum and Loerbeeka a stone was tied to the end of a rope

instead of a piece of lead.

After a short but strenuous effort, the raisers [richters]

had the bent upright, but the raising was by no means finished.

The bent still had to be lifted onto the piers. If it was raised

and lifted onto them simultaneously, they were likely to break

unless they were protected with planks or, as in Wehl, with temporary

piers [noodpoer] made of loose stones. However, the bents

were almost always erected next to or directly in front of the

piers and subsequently lifted onto them.

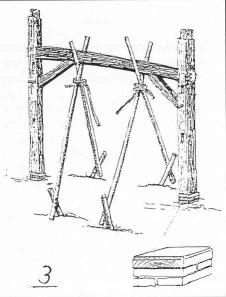

<-Drawing

3. <-Drawing

3.

One of the methods used to lift the bents up was

to put pieces of wood under both ends of the iron rod at the bottom

of the post and heave it onto the pier (See drawing 1.) or to put

a crowbar under the rod and lever the post onto the pier. In other

places a piece of wood (In Hengelo, it was called a kluppeltjien)

bound to the posts with a chain or rope was used instead of a rod.

The first bent raised was the one next to the solid wall that

would separate the threshing floor/working space [deel]

from the kitchen [keuken]. This had to be carefully braced

so that it didn't shift or fall over. The same long volgers that

had been used to raise the bent could be used as temporary braces.

These were nailed to shorts posts that had been set in the ground.

[See drawing 4.] However, not all carpenters used four long volgers,

two crossed poles bound together with a chain were sometimes used

instead, i.e. the same kind of poles that were used as volgers which

were not attached to the posts. In Marienvelde these temporary

braces made from two poles tied together [See drawing 3.] were

called schankel; in Larense schranken, in Eibergen

the carpenters called all the temporary braces, whether they were

fastened to the bent or not, schrankels or schrankpaole.

In some cases, poles were used that were too light for volgers, so

that the stronger poles could be used to raise the next bent. A

carpenter from Laren said that they used four fir trees as temporary

braces.

<-

Drawing 4 <-

Drawing 4

In many places, oaks pads [kusn] about 3 to 6 centimeters

larger than the ends of the posts were placed on the piers to distribute

the load. This also prevented the bottom of the posts from rotting

so quickly. Particularly in the 1920s and 30s, when poplars were

used for the posts, these pads were very effective. However, there

was no agreement among the carpenters interviewed. Some of them

thought oak pads were a sign of quality joinery; others thought

it was just the opposite because pads were sometimes used when

a post or a pier was too short. [See drawing 3.]

Sometimes a lead plate was put between the posts and the piers.

Many, but by no means all, of the carpenters interviewed felt that

this was a mistake. They only did this if the architect demanded

it. They thought that water collected on the plate and the posts

rotted faster than ever. They felt the lead plates were a sign

that architects were full of all kinds of theories, but lacked

practical experience.

To give an impression of how an experienced carpenter described

raising a frame, the author included an excerpt from the story "Besvaar",

one of the Middewinteraovend vertelsels written by the carpenter

and author Hendrik Odink from Eibergen. In the chapter called 'n

Schoer [The Barn], Odink gives a short description of rebuilding

a farm after a fire caused by a terrible storm. It is the only

description of a traditional farm in East Gelderland by an expert

that he had found. The author says that it's surprising that the

men in the story used only their hands and shoulders to raise the

bents. All the oral witnesses in East Gelderland reported that

some sort of equipment had been used. The men in the story did

use ladders, however, but only to reach them the tops of the bents,

not to shove or brace them. In the story, however, safety ropes

were used. These were held by the women from the farm.

Finishing the frame

As soon as the first bent was standing upright, the connecting

girts were fastened to the bent with trenails. (Drawing 4 shows

an upright bent with temporary braces attached to the raising holes,

the tenon of the connecting girt inserted in the mortise and the

other end of the girt resting on an X-shaped brace.) While the

second bent was being raised and heaved onto the piers, two men

stood at the ends of the girts to guide the tenons into the mortises.

Then the trenails were quickly hammered in. Now the frame stood

firmly on four "feet" and there was no longer any danger

that it would fall over. That is why particular attention had to

be paid to bracing the first bent raised, but not the subsequent

ones.

The rest of the bents were raised and connected by the same method.

After they had all been erected all that was left to do was to

put the plate [bovenplaten] and the braces [spreitbanden]

on. This, too, was done with the help of the farmers and the rest

of the team. First of all, planks were placed from beam to beam,

so that the workers could walk from bent to bent. Then the braces

were connected to the posts, but the trenails were not hammered

all the way in so that they could still be moved up and down a

little. The available timbers were apparently not long enough to

make the plates in one piece,(10) so that with the help of a few

men, the individual pieces had to be laid on top of the rows of

posts, the tenons of the posts and braces inserted and all the

trenails hammered in.(11)

This detailed description of raising a timber frame is a rare

document. East Gelderland is a very small area the entire province

of Gelderland is only 1,965 square miles in area. It is surprising

that such a variety of methods and simple equipment was used and

was still being used to raise anchor-beam bents in the first half

of the 20th century.

1 This article should be preceded by one on Hallenhause,

in particular the ones in the open air museum at Detmold, but I

am still putting the finishing touches on that one.

2 Prooije, L.A. van / drawings by A. J. Hemels (Reprint 1997). De

vakleu en et vak:Boerderijbouw in Oost-Gelderland vanaf de eeuwwisseling

to Ca. 1940. Vaktermen en werkwijze. (Craftsmen and their

Craft: Farm Buildings in Eastern Gelderland from the Turn of

the Century until about 1940) Arnhem, Stichtung Historisch Boerderij-Onderzoek

(Institute for Historic Farms Research). The original publishing

date was not included in the information sent.

3 For example (Opderbaecke 1921) [The Carpenter] This book was

designed for use in trade schools and for students of building

engineering. Opderbaecke was principal of the state school for

the building trades in Munster/Westfalia. Very few of the 311 pages

don't have any drawings; most of them have several. It does show

various ways to erect scaffolding.

4 (Simons 1998) p. 89

5 (Prooije and Hemels 1997), pp 49-55

6 These pages were not included in those Dr. van Olst sent.

7 The place names are included, so that they can be compared

to the genealogy of American Dutch barns.

8 The Dutch words used in timber framing have been included as

far as possible.

9 "... halsreikend naar deze dag uitgekeken."

10 The making of the plates was described in chapter 4.

11 The text sent to me ends here, at the end of page 55.

Ms. Karen Gross is a noted preservationist of Breitenheim,

Germany.

NEWSLETTER

FALL 2000, Vol. 13, Issue 2,

part two

|