|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER

FALL 2003, Vol. 16, Issue 2, part two

The big Gooi-style

farmhouse at Greenbush after over fifty years be came very dilapidated.

When Jeremias Van Rensselaer, who became Director of the Rensselaerswyck

colony in 1660 took over the farm at Greenbush for his own (and

named it Crailo), he refused to use the old farmhouse because

of the expense of maintaining it. But he did not tear it down.

In 1661 Van Rensselaer leased the farmhouse at Greenbush, (but

not the farm) to Willem Bout for six years, on the condition

that repairs to the building were to be at Bout's expense. Bout,

to whom the Greenbush sawmills belonged, complained often that

he did not care to live in the run-down farmhouse because of

the costs. Jeremias van Rensselaer noted, however, that the house

was conveniently located for Bout because it was close to the

mill on the present day Red Mill Creek. Bout was not allowed

to build any new structure close to the mill nor to pile firewood

or hay near the mill.

Figure

12. The two side by side Bronck houses surviving at Leeds, New York,

show two different styles for country houses. The older house of

1663 is at left. Photo by Robert Andersen. Figure

12. The two side by side Bronck houses surviving at Leeds, New York,

show two different styles for country houses. The older house of

1663 is at left. Photo by Robert Andersen.

In November,

1662, Van Rensselaer and Bout altered their agreement into an

arrangement for rent of a small part of the farm. Bout was to

keep the house and the out buildings at Greenbush as he had previously

had them. He was also to have a good work horse and a heifer.

In 1670, a complaint was made that Willem Bout's horses at the

mill sometimes got into the Greenbush farmer's fields. About

the time Bout died in 1683 the decrepit farmhouse of 1632 may

have been abandoned.(12) The Greenbush farmhouse did not wash

away in the famous flood of 1666 which destroyed many buildings,

including the matching farmhouse on Castle Island. Because it

was rented, the old farm house at Greenbush probably lasted longer

than most of the others of its type. By 1668, the one at the

Flatts fell in and had to be rebuilt.113) It appears the big

Gooi farmhouses were not practical in the cold Hudson Valley

climate of the 1600s. On the additional Rensselaerswyck farms,

residences began to be built separately from the barns.

Cellars, at

first merely holes in the ground framed with boards under the

living area of a farmhouse, were needed to provide frost free

storage for root crops and fruit. For example, in Arent Van Curler's

long farmhouse on the Flatts, there was to be a small cellar

under the dwelling section. As the free-standing farm residences

became common, full cellars made of stone gradually replaced

the partial cellars. These stone foundations now supporting the

residence avoided frost heave and rot, which probably had afflicted

the large farmhouse combinations.

Figure

11. A late twentieth-century photo of the Van Bergen barn shows

the roof had been altered. Photo by Jeanne Litwin. Figure

11. A late twentieth-century photo of the Van Bergen barn shows

the roof had been altered. Photo by Jeanne Litwin.

The Dutch barns, I believe, in being separated from the farm residence,

retained the framing shown in Jaap Schipper's sketch of the Gooi

barn, with possibly the elimination of an angle in the roof slope

over the side aisles. [Figure 11] A photograph shows.the a1tered

framing of the roof of the 1680 Van Bergen barn. Whether this change

was merely to raise the roof for more hay storage, or whether it

was to eliminate the break in the pitch is not known. In the Netherlands,

there was a short age of long timbers for rafters, while here,.

due to the long timbers available, there was no need for a rafter

splice over the side aisles. In another adaptation after residences

were separated from the barns, the big wagon door was brought around

from the side of the barn to the gable end, thus avoiding the need

to raise the eaves for a wagon door.

The Gooi barn and the Kiliaen van Rensselaer's letters help us

to understand why some house contracts of the seventeenth-century

in the Hudson Valley called for houses which were wider than deep.

[Figure 12: Two Bronck houses, 1663 and 1738, side by side.] The

Bronck house of 1663, for example, is 26 feet across the front,

while it is only 22 feet deep, modern measure. I am not suggesting

that this particular house once had a barn attached at the rear,

although it might have, since

it has the right proportions to be the residence part of a longhouse.

In another example, the living section of the longhouse built on

the Flatts by Arent Van Curler was to be 28 feet wide by only 20

feet in depth, again wider than it was deep.

Thus the wider than deep

pattern in houses may reflect proportions established when Van

Rensselaer's Gooi longhouses were erected.

This brings into question

our assumption that any Dutch-style house with its front door

in the gable end is an urban-style house, while houses such as

the second Bronck house of 1738, with a ridge running parallel

to the road, are thought to be "country-style."

Actually, the tradition of a gable end to the road is an ancient

one, not limited to cities. As we have seen, country farmhouses

with attached barns in the Gooi style had to be entered from the

gable end and this may explain why the occasional Hudson Valley

Dutch country house gable faces the road.

Summary

The longhouses of the Gooi land were, just as Kiliaen Van

Rensselaer intended, one big efficient rectangle. They served their

purpose, providing quick shelter for farm families, farm help,

stock and crops in the first years of farm settlement here. These

special European farmhouses of the Gooi once were a part of our

landscape. They are documented by letters, by archeology, and by

Dutch architectural. studies. Moreover, their framing style set

the pattern for the Dutch-American barns of the next two centuries,

and influenced house shapes as well. This large, influential (but

little appreciated) European style building lurks in the background

of our architectural history.

EXTRA

I will read you a story about the farmhouse in Greenbush which

has nothing to do with architecture.

In 1632 an unpopular man, Hans Joris Hontum, was selected to

be commissioner of Fort Orange. The Mohawk Indians hated him because

a decade earlier he had cold-bloodedly murdered a captive Mohawk

chief after the chief's ransom had been paid. When he arrived at

Fort Orange, the Mohawk Indians rose up in violence, killed cattle

(including at Greenbush), and burned a yacht. They threatened to

kill Hontum, and refused to trade with him.

More violence followed the appointment of Hontum. Within a year

he was stabbed to death in Van Rensselaer's farmhouse at Greenbush

by Cornel is van Vorst, chief officer of Pavonis, a patroonship

near New Amsterdam. The details were given by Cornel is Maesen

(Van Buren), who returned to the Netherlands in 1634 after three-and-a-half

years as a farmhand in Rensselaerswyck. Cornelis Maesen, who had

gone outside just before the fight began, heard the details from

the others present. He explained that Hontum, by order of the Dutch

West India Company directors, had posted a placard restricting

trade with the Indians. Cornel is van Vorst resented this regulation

and held it against Hontum. When van Vorst visited Hontum at Fort

Orange in April 1634, they began to drink together. Then the pair

crossed the river to visit the "dwelling and farm of Rensselaer

where he, the deponent [Cornel is Maesen] resided." The two

officials entered the house on the Greenbush farm, in which, after

drinking some more, van Vorst made insults against council members.

When Hontum struck him in the face, van Vorst drew his sword and

fatally stabbed him.

Notes:

(1) Jonathan Pearson, trans. And A. J. F. Van Lear, ed., Early

Records of Albany, Vol. 2, (Albany: University of the State

of New York, 1916), p. 154; Early Records of Albany, Vol.

3, (Albany: University of the State of New York, 1918, pp. 508-509).

(2) A. J. F. Van Lear, Trans. And ed., Van Rensselaer Bouwier

Manuscripts (Albany, NY 1908) p. 308 [hereafter cited as VRBM.

(3) Ibid, p. 309.

(4) From J. J. Voskuil, Van vlechtwerk tot baksteen, (Stichting

Historisch Boerderij-Onderzoek, Arnhem, The Netherlands, 1979),

po, 35, copied with permission.

(5) "Settlement Patterns in Rensselaerswyck: The Farm at

Greenbush," de Halve Maen Magazine, Summer, 2002, Vol.

LXXV, No.2, p. 23).

(6) VRBM, p. 309.

(7) VRBM, p. 520.

(8) Paul R. Huey, "Archeological Evidence of Dutch Wooden

Cellars,"

in New World Dutch Studies: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial

America, Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987, pp. 14-16;

A. J. F. Van Laer,

"Translation of the Letter of Arent Van Curler To Kiliaen

Van Rensselaer," Dutch Settlers Society of Albany Yearbook,

Vol. 3 (1927-28), p.2l.

(9) Shirley Dunn, "Settlement Patterns: the Farm at Greenbush," de

Halve Maen, Summer, 2002, Vol. LXXV, No. 2, p. 23.

(10) VRBM, p. 820.

(11) J. Franklin Jameson, Narratives of New Netherland (1909)

reprint, New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1967, p. 262.

(12) For details given in this paragraph, see Dunn, "Settlement

Patterns: Greenbush," de Halve Maen, Fall 2002, p.

50. For Bout's death see Jonathan Pearson, Contributions for

the Genealogies of the First Settlers of the County of Albany,

reprint, Genealogical Publishing Co. 1978, p.5.

(13) In. 1666, the patroon's house in Albany where Jeremias and

his wife, Maria, lived was washed away by a catastrophic April

flood on the Hudson River. Almost all their possessions and papers

were lost as well as the colony's grain stored for shipment. Many

other buildings onshore, as well as barns and houses on the islands,

were destroyed, but the Greenbush houses were exceptions. A few

days after the flood, Jeremias Van Rensselaer wrote, "My farm

in the Grene Bos is, thank God, saved beyond hopes which I had

of it. I lost there not more than two cows and one heifer, one

half of my hogs and a large part of my fencing." Correspondence

of Jeremias Van Rensselaer, A. J. F. Van Laer, trans. And ed.

(1932), p. 106. For the need to reconstruct the house at the Flatts,

see ibid, 407.

(14) John Stevens, "A Last Look at the Van Bergen-Vedder

Barn,"

Dutch Barn Preservation Society Newsletter, Spring 1995, Vol. 8,

Issue 1.

Shirley Dunn, historian, author, and lecturer

was one of the founders of the Dutch Barn Preservation Society

and its first president. Among her books is the monumental work, "The

Mohicans and Their Land."

WINDMILLS

OF HOLLAND

This brochure, received from Jaap Schipper, society member from

Amsterdam, Holland is included here to demonstrate how others handle

preservation with problems very similar to the American-Dutch barn.

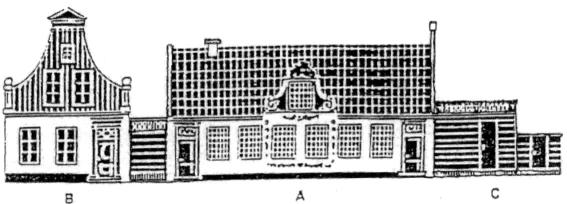

Museum Building

The Windmill Museum was opened in 1928 by Prince Hendrik,

husband of Queen Wilhelmina.

For over 60 years, the windmill Museum has been housed in a reinstated

old Zaan merchant house, built around 1760 at Koog aan de Zaan

(A).

The brick facade facing the park side is richly decorated with

carved wooden ornaments.

The main building (A) is divided between a ground floor, the

model replica room with print cabinet and an upstairs department

devoted to crafts and technique.

In

1982, the museum was doubled in size by reconstructing next to

the first building, a second merchant's house, originally built

in Zaandam (B). Of interest in this building is the authentic roof

beam construction from the 17th century using curved oak beams

as corbel. In this part of the museum (B), is downstairs a space

for changing exhibits and upstairs an exhibit about the history

of windmills. In

1982, the museum was doubled in size by reconstructing next to

the first building, a second merchant's house, originally built

in Zaandam (B). Of interest in this building is the authentic roof

beam construction from the 17th century using curved oak beams

as corbel. In this part of the museum (B), is downstairs a space

for changing exhibits and upstairs an exhibit about the history

of windmills.

In 1989, the museum was further expanded with a panorama room

(C) which includes the "Zaan Windmill Panorama" by Frans

Mars.

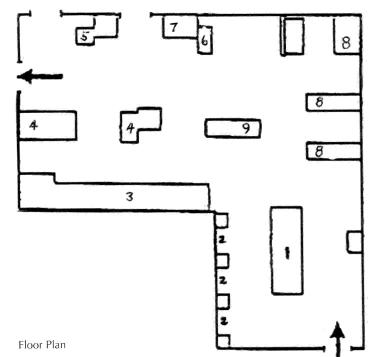

1. Models of windmills

The first object to catch your eye is the large-scale model

of the paper windmill "De Eendracht", constructed at

the workshop of P. Wakkar at Wormer in 1900 (A). Seven men worked

on it for more than six months.

2. The information panels

The Netherlands has long been known for its windmills. Around

the middle of the last century, there were still 9000 of them.

However, through fire and demolition, the number of windmills has

been drastically reduced. Now there are only about 1000 remaining.

Whoever wants to see this still existing heritage has many opportunities.

Windmills are spread throughout the land and in large variety.

The industrial development along the Zaan river began about 1600,

progressing greatly in the 17th and 18th centuries. Lumber was

sawed, oil pressed, paper was made, rice and barley peeled, cloth

fulled, hemp pounded, grain, snuff, cocoa, color pigments, spices

and mustard seed ground. (Green lamps indicate the still existing

windmills.)

By 1730, roughly 600 mills were running simultaneously in the

Zaan district. After 1750, prosperity slackened. A difficulty period

ensued which saw the destruction of many mills. The arrival of

the steam engine in the industrial revolution after 1870 meant

still further damage. By the turn of the century, even more windmills

disappeared through fire or demolition. Presently, there are only

a small amount left over, most of which are in the possession of

the Zaan Windmill Association.

3. Drainage Mills

In the Netherlands windmills were used for the reclamation

of land from lakes. The firth drainage mills used a paddle-wheel

to draw up the water. Since 1650 an Archimedean screw made from

wood has been used as well, enabling the water to be drawn up from

a considerable lower level. The Polder windmills in the Low Countries

called Noordholland have no tail construction in order to revolve

the cap and put the sails into the wind. The caps of these windmills

are turned by means of an inside winding gear.

4. Sawmills

The first saw mill was built in the year 1592. The Zaan district

once numbered about 240 Poltrok saw mills which revolve as a whole.

The much larger type sawmill with revolving cap and reefing platform

was used for sawing the largest trunks.

5. Wind mills

The oil windmills produced vegetable oil and cattle food by

grinding different kinds of oil seeds and expelling the oil at

high pressure. One of the scale models shown here was made by J.

Nanning around the year 1796 by candlelight in his free time.

6. Dye windmills

In the dye windmills, the wood containing pigments was ground

to powder. With these colours, wool, silk and cotton clothes were

dyed. Pigment mills pulverized minerals to powder which artists

used to lubricate paints.

7. Peeling windmills

With the help of rotating stones, the hull of barley and rice

was peeled.

8. Guilded bronze models

The bronze models were produced in 1928 by "Ateliers

A. Schoorl"

to the design of P. Boorsma, one of the Zaan district's best windmill

experts.

9. Wooden models

These miniatures, made from tropical wood, were created between

1938 and 1948 from designs by Jos van der Horst.

MOLENMUSEUM/ Museum/aan 78/ Koog a/d Zaan, Netherlands.

The Wortendyke Barn Museum is an excellent community

attraction at 13 Pascack Road in Park Ridge, N.J. Photo by Curator

Robert L. Cohen.

NEW FITCHEN BOOK RECEIVES AWARD

Congratulations to Greg Huber, recipient of the Allen G. Noble

Book Award for the best edited book in North America, for 2003,

given by the Pioneer America Society. Greg received the award for

his editing and expanding with new research the original work of

John Fitchen in his 1968 published book, The New World Dutch

Barn. Readers may enjoy the review of Greg's book by Peter

Sinclair, which appeared in the Fall 2001 issue of the Dutch Barn

Preservation Society Newsletter.

|