|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

FALL 1998 VOL. 1, ISSUE 2

Agrarian

Changes: Learning from Barn Additions

By Neil Larson

Dutch barns are extraordinarily rich documents of life in our past.

Built across two centuries and adapted to new uses for another

one hundred years, the barns are a fusion of Old World traditions

and New World innovations; their evolution offers insight into

a changing agricultural society and illustrates evolving building

technology.

Originally, Dutch barns were designed for use in the growing,

storing and processing of wheat. The wheat industry dominated the

Hudson Valley economy until the early nineteenth century; in the

Schoharie and Mohawk valleys, wheat was the major crop into the

1840's. In each region, as blights occurred and rising non-farm

populations increased the demand for fresh market products, large-scale

crop farming shifted from wheat-growing to milk production. Nearly

all of the surviving unrestored Dutch barns show evidence of alterations

to meet the requirements of changing farming practices. These alterations

often make it difficult to discern the original appearance and

functions of the barns, but a study of these additions and renovations

provides an understanding of the barn in the context of the changing

occupational patterns and cultural attitudes of the ethnic communities

that built the barns and continued to use them.

When the function of the Dutch barn changed to accommodate dairying,

the spaces within it were rearranged and augmented to house more

animals, to provide easier access to the fronts and rears of animals

for feeding, cleaning and milking, and to store hay in addition

to grain.

The early eighteenth century Johannes Skinkle Barn

on Route 9H, Columbia County, NY was altered by the insertion

of new wagon doors. The original door openings in the gable ends

were covered with siding. Photo by Shirley Dunn.

One popular alteration was rotating the center aisle axis 90

degrees and inserting new doors on the side walls, creating a plan

more akin to English barns of the period. In addition to increasing

the space for animals, changing the access so that the aisle went

between anchor beams rather than under them allowed more headroom

for hay wagons. Most other existing barn types in New York State

and elsewhere were also modified in this dairying period as moving

and storing hay more easily within the barn became a matter of

major concern. (Dutch barns actually accommodated hay track systems

better than English barns since their roof framing did not rely

on collar beams.)

The reorganization of interior storage space for feed and bedding

was easily accomplished; however, introducing space for an increased

number of cows required physical alterations to the barn. If an

addition was not feasible, farmers would construct stanchions in

the side aisles or at one end under a hay mow. In some cases, an

entire floor was constructed just under the anchor beams to create

a cow house on the ground level and hay storage above, but this

must have been done after grain was no longer threshed in the barn.

A more radical solution was to raise the old barn on a stone basement.

This innovation was a direct response to the progressive agricultural

literature of the period, which advocated housing livestock at

a basement level for ease of handling and feeding.

Raising the roof was an alternative for increasing the volume

of Dutch barns, at least in the western reaches of the Hudson Valley,

where a few examples survive. New sections of posts approximately

five feet high were inserted above existing posts and purlins.

New purlins with braces then tied the new posts together. In the

illustrated example, the original roof framing was apparently reused,

necessitating elevating the side walls an equal height. The direct

result of this change was increased capacity for hay storage; however,

physical evidence suggests that it usually coincided with a complete

reorganization of space within the barn which created cow stalls

in a side aisle and at one end of the barn.

In addition to adding to the tops and bottoms of Dutch barns,

farmers increased barn size by adding to the ends. Field investigations

indicate that the common choice for an addition was to extend the

length of the barn with construction of a similar form along the

same roof axis, in effect creating a longer, rectangular barn.

Side doors, ramps into upper level hay mows, excavated basements

and other alterations were often introduced at the same time. In

the Schoharie Valley, while end additions were sometimes made,

there are a number of examples unique to that region in which separate

rectangular barn frames were abutted perpendicularly to the ridge

line of the old Dutch barns.

The Godigheit Barn, Schoharie County, NY shows

a perpendicular addition at the rear that was typical of the

Schoharie Valley. Photo by Harold Zoch.

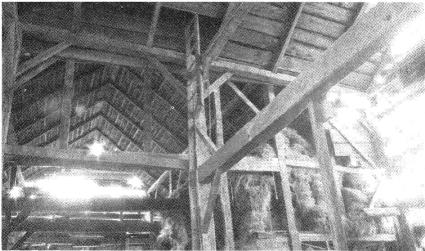

View of interior of the Godigheit Barn is from

the addition looking into the old Dutch barn in the background.

Photo by Harold Zoch.

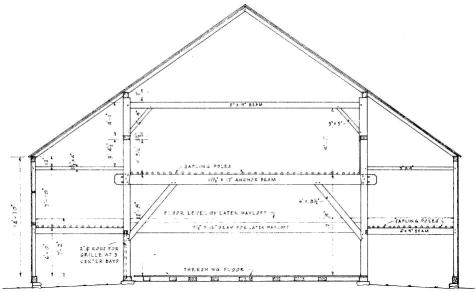

New

4'8" sections were added to the posts above the existing

purlins to raise the roof on the Johannes Decker Barn, Shawangunk,

Ulster County, NY. New purlins were added to support the roof

rafters. All new members were mill-sawn with a circular blade.

Posts were sawn with a tongue to overlap the old post and bolted

fast. Note hayloft added in rear creating animal space below. Historic

American Buildings Survey: New

4'8" sections were added to the posts above the existing

purlins to raise the roof on the Johannes Decker Barn, Shawangunk,

Ulster County, NY. New purlins were added to support the roof

rafters. All new members were mill-sawn with a circular blade.

Posts were sawn with a tongue to overlap the old post and bolted

fast. Note hayloft added in rear creating animal space below. Historic

American Buildings Survey:

Construction in additions sometimes replicated the Dutch methods

but in every case the new structures were in sharp contrast to

the old, with later builders often using less substantial materials

and displaying far less concern for craftsmanship than had the

original builder.

Dutch barns are "Dutch" as much for the cultural group

they came to symbolize as for their form and structure. Their distinctive

construction method was derived from the well established aisled

barn tradition of northern Europe. The "Dutch" -ness

of these barns, however, is actually less dramatic in their direct

transplantation in the seventeenth century from the wheat-growing

areas of northern Europe to the wheat-growing areas of colonial

New York and New Jersey than in the persistence of their image

on the landscape in the rapidly changing society and economy of

this region following the Revolution.

With nationhood, rural ethnic communities in these old "Dutch"

valleys were forced to defend their identities against the onslaught

of vast numbers of newcomers and the snowballing momentum of

the frantic popular culture wrought by independence and the idea

of unlimited opportunity. Therefore, while Dutch barns were being

transformed to new functional requirements, the region was in

the midst of a battle between old and new, for cultural supremacy

that found vivid expression in politics, religion, social behavior,

the arts. . . and architecture. The amount of conscious, non-essential

effort that went into the construction and preservation of the

Dutch barns suggests that these buildings also served as emblems

of ethnic solidarity. The final analysis of functional changes

in these buildings will not be complete until this expressive

dimension of cultural continuity in their design is addressed.

Neil Larson is Curator for the Dutchess County

Historical Society. He was formerly with the N.Y.S. Field Services

Bureau.

FALL

1988 Newsletter, Part TWO

|