|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER

FALL 1992, Vol., 5, Issue 2

A

PHOTO ESSAY

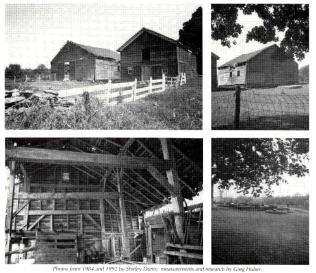

The Dutch barn pictured stood on Wurtemburg Road, near Rhinebeck,

Dutchess County. When it was photographed eight years ago, a

survivor of over two centuries of service, the carved date of

1759 was visible in the center of the first anchorbeam. The structure,

a typical Dutch barn of three bays with a manger on the east

side, later collapsed.

The ruin was among Dutchess County barn sites visited by the

Dutch Barn Preservation Society trustees on a tour in May, 1992.

The foundation of the ruined barn measured 43' (width at the

gable end) by 42' deep; the anchorbeams were 11" by 8" supported

by 10" by 8 3/4"

columns. The threshing floor was 18' wide, flanked by 12' 6" aisles.

Named for an area in Germany, the Wurtemburg Road locale was

settled by Germans rather than by the Dutch. However, the owner/builder

of this particular barn is not known.

New World Dutch Farms: A

Selection of Distinctive Objects

By Roderic H. Blackburn with contributions

by Willis Barshied, Jaap Schipper and Anthony Sassi

Continued from the Spring, 1992, issue.

The Dutch Sith and Mathook

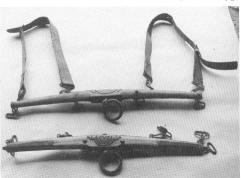

Among the hand tools that were distinctively Dutch were the sith

and mathook. Kiliaen Van Rensselaer in 1632 wrote to Wouter van

Twiller, his nephew and director of his colony of Rensselaerswijk

that he was sending

"12 grass scythes/19 sichten - [siths or Flemish scythes]

for grain". A ca. 1634 inventory for goods sent to the same

place listed "4 long grain scythes" and "4 sichten

- for grain".(1)

The sith [also designated as sicht, zicht, sicht, sythe, Flemish

scythe, Hainault scythe (a misnomer as in that province it was

not used) and other variations] was the reaping tool of Dutch preference

for centuries. Like the Dutch plow, it appears in 16th century

illuminated Flemish manuscripts(2) and later paintings and engravings.

From northern France to Northern Germany it had wide acceptance,

reflecting its greater efficiency over both the small sickle and

the large scythe. It allowed a man to stand nearly erect, the sith

balanced comfortably in his right hand, and slash the grain more

easily because the crooked shaped handle braced much of the effort

against his wrist and lower arm. Without his having to stoop over,

the reaping hook [mathook] in his left hand held the stalks together

at an angle to more easily cut them, then deftly position them

on the ground for subsequent binding into sheaves.

Typical of various references to the sith, Laurens van Alen, proprietor

of a farm in present Columbia County, in 1672 sued a tenant farmer

for

"certain missing tools, including a Flemish scythe, an auger,

a mattock, a flatiron, and a small fork." Yet, about one hundred

years later, Richard Smith wrote that "... a Scythe with a

Short crooked Handle and a Kind of Hook both used to cut down Grain

for the Sickle is not much known in Albany County or in this Part

of Duchess." (3)

A number of examples of the sith and mathook survive, most having

been found in the Mohawk Valley where Dutch (and German, for both

made and used identical objects there) farm practices persisted

into the mid-19th century, longer than elsewhere. One sith is marked

1821, and other blades are stamped for S. and A. Waters, makers

active from 1812 in Amsterdam, Montgomery County. Sith handles

show considerable variation, not only between European and American

versions, but within the existing American examples suggesting

regional and likely individual variation. Carved usually from two

pieces of wood, some are more finished than others, suggesting

that at least some were farm-made rather than craftsman-made. The

mathook was also carved to insure a comfortable grip and a similar

bracing of the long handle against the arm for greater leverage.

Not illustrated here, but worth mentioning, is a Dutch anvil and

hammer specifically made for sharpening the sith blade in the field.

The anvil is in the shape of a big cold chisel or wedge about a

foot long with a lower pointed end which is driven into the ground.

The upper end widens to receive the blows on the sith blade edge

using a special narrow-headed hammer.(4)

The sith and mathook were well suited to wheat (often called corn

in early accounts, especially by English speakers) harvesting.

They were also used for cutting peas, a crop which was often alternated

with wheat. In the province of Zealand in the Netherlands that

was their sole use.

Each shock of summer wheat contained twelve sheaves, each shock

of winter wheat or rye contained eighteen sheaves. In order to

dry the sheaves on all sides the shocks had to be turned.

In Uit Het Oude Friese Akkerbouwbedrij,

Leeuwarden, 1981. Illustrated by drawings done by Ida Wiersma

(1878-1965) ca. 1906-1932.

"At the wheat harvest the wheat was cut with the sith. The

cut stalks were shaped into a sheaf with the mathook and the right

foot. Then the sheaves were bound by the binders and finally put

in shocks to dry."

Curiously the

English showed persistent reluctance to adopt the sith despite

its efficiencies. Both in England, where it was advocated and

demonstrated without effect, and in New York when great numbers

of Yankees swept into New York after the Revolution, the Englanders

stuck to their own sickle and long-handled grass scythe. Only

in the nineteenth century when the demonstrably more efficient

cradle scythe was introduced and adopted by all ethnic groups

did the Dutch begin to give up the sith and mathook.

Other Dutch Objects

Of the hundreds of objects once part of Dutch farms only a fraction

can be physically identified today. Most objects have been lost

or destroY!2d and of those surviving most have lost their "Dutch" connection

to a specific family or farm. We have to rely on those few still

on family farms or in catalogued public and private collections

as a guide to what was characteristic of early farms in New York

and New Jersey. Most objects probably will prove to be so similar

to New England or European examples - early engravings and paintings

demonstrate how little many tools have changed - that their "Dutchness" will

never be obvious. Where an object has retained in English usage

its Dutch name (sith, mathook) or the word "Dutch" as

an adjective (Dutch plow, Dutch wagon),we can be more certain that

it was once viewed as distinctly Dutch in form or style. Such is

the case with the grain measure used by the New World Dutch which

retains its old name, schepel. Its capacity is certainly non English,

as it holds the odd amount of .764 English bushels. In Dutch measure,

three schepels equaled a zat, four zats a mudde, and 27 muddes

a last (85.512 bushels).

A whiffletree-like object was once identified by Rufus Grider,

a knowledgeable historian of Mohawk Valley life, as a "Dutch

neck yoke". How it and others could be used as such is not

clear from the several examples which have been found in the Mohawk

Valley. What distinguishes them from the more conventional whiffletree,

which connected a horse's two traces to the pulled object (plow,

wagon etc.) is the greater number of attaching swivels, eight instead

of two. One example survives with parts of the harness straps attached.

Less puzzling is the decorative iron work, which is shaped in a

heart design, a touching symbol of the farmer's true affections.

Sith and mathook found in Montgomery

County, NY. Collection of Willis Barshied.

Schepel

used by Johannes Ball, chairman of the Committee of Safety, Schoharie

Frontier, during the Revolution. Height 10 inches, diameter 15

1/4 inches. Pine and wrought iron. Collection of the Schoharie

County Historical Society, Schoharie, NY. Schepel

used by Johannes Ball, chairman of the Committee of Safety, Schoharie

Frontier, during the Revolution. Height 10 inches, diameter 15

1/4 inches. Pine and wrought iron. Collection of the Schoharie

County Historical Society, Schoharie, NY.

"Dutch neck yoke", a whiffletree-like

object, the upper one with early harness straps. Collection of

Willis Barshied, Palatine Bridge, NY.

Another Dutch object is a type of harness composed of a chest

and shoulder strap, not the neck collar we associate with a working

harness. Examples have been found in the Mohawk Valley which match

illustrations of harnessed horses pulling wheel plows in the Netherlands.

Many "wagon seats" are circulating around the antiques

trade and may have been the type used on Dutch wagons, but one

description mentions wooden springs, not the well known chair posts.

And what of the carts mentioned in Dutch farm inventories? Not

one today is clearly identifiable as coming from a Dutch farm so

we don't know if it was as distinctive in construction as the Dutch

wagon.

One sleigh dating from the later part of the eighteenth century

with a tradition of ownership by General Peter Gansevoort of Albany(5)

may be Dutch in character.

Like so many of the objects listed in inventories, most will

await the stimulated inquiry of the reader to uncover them from

Dutch farms or from illustrations of Dutch objects in far flung

publications and art works. Let us share discoveries in the Newsletter

and Miscellany as they are found to build a useful archive of all

the objects which the mother of objects, the Dutch barn, has preserved

for us.

ENDNOTES

1. Van Laer, A. J. F., Van Rensselaer-Bowier Manuscripts.

Albany: University of the State of New York, 1908. p. 204. Ibid,

p. 264.

2. "The Month of August", from Hours of the Virgin

and Kalendar for Strassburg Use. Illustrated in Peter H.

Cousin's authoritative Hog Plow and Sith, Cultural Aspects

of Early Agricultural Technology, Dearborn: Greenfield Village

and Henry Ford Museum, 1973. p.23. The most complete source on

the sith, on which much of this section is based, comes from

this source.

3. Van Laer, A.J., Minutes of the Court of Albany, Rensselaerswyck

and Schenectady. Albany: University of the State of New York, 1926,

p.302. Smith, Richard, A Tour of Four Great Rivers/ the Hudson,

Mohawk, Susquehanna and Delaware in 1769/ Being the journal of

Richard Smith of Burlington, New Jersey, Edited by F. W. Halsey,

Port Washington, New York: Ira J. Friedman, 1964. p.11.

4. For further information on the sith, mathook, and other Dutch

farm tools see David Steven Cohen's "Dutch-American Farming:

Crops, Livestock, and Equipment, 1623-1900" in New World

Dutch Studies, Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America 1609-1776,

Roderic H. Blackburn and Nancy A. Kelley (eds.). Albany Institute

of History and Art, 1987, pp.194-198. For further information on

the sith see: "A Symposium, Questions about Dutch agricultural

tools in America." with contributions by Willis Barshied Jr. "In

defense of the term 'sith' " (pp.65-66); Francis York "Peculations

about the origin of the word mathook"

(pp.66-67); Charles Reichman "Barton of Mayfield and the Dutch

scythe"

(p.67); and Richard Kappeler "A Dutch? scythe anvil" (p.68).

This appeared in The Chronicle of the Early American Industries

Association, March, 1975. In the December 1987 issue, Willis

Barshied Jr. added an

"Editorial addendum" on the subject, and Robert Fridlington

wrote "Sith vs. scythe, another view"; followed by "The

pith of the matter, a response from the editor". Peter Sinclair

illustrated and discussed several Hudson Valley siths in "Five

siths and a mathook from Ulster County, NY" in Field Notes

of the Joy Farm Preservation Society, Autumn, 1991.

5. Collection of the Museums at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, Long

Island, NY.

Society Activities

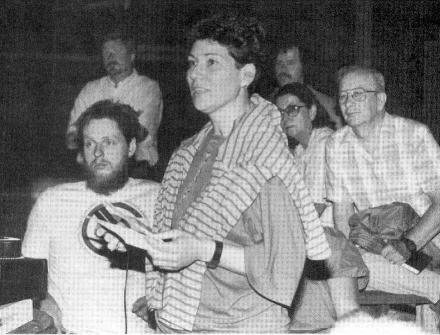

DBPS members listened intently on June 16, 1992 to Ellen van Olst,

Director of the Stichting Historisch Boerderij-onderzoek, a barn

preservation group headquartered at Arnhem, The Netherlands, as

she showed slides illustrating regional differences in barns in

the Netherlands. From left, Jack Sobon, who arranged the talk in

connection with the Timber Framers Guild, R. Andrew Nash (rear),

Michael Bathrick, Rivkah Feldman, and Harold Zoch. Photo by Clarke

Blair.

Differences noted by Ms. van Olst between old barns in the Netherlands

and Dutch barns near Albany included: multiple use there rather

than single use; smaller scantlings (timbers) and imperfect timbers

used in Netherlands barns; floors in Netherlands barns made of

clay, not wood, with no flooring framework, and posts resting on

stones; roofs in the Netherlands covered with thatch or pantiles;

siding there may be wattle and-daub or brick infill between posts

(studs); lower aisles (eaves) in the Netherlands; house (residence)

may be attached at one end.

|