|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

FALL 1993, Vol. 6, Issue 2

Vincent

J. Schaefer, 1906 - 1993: A Remembrance

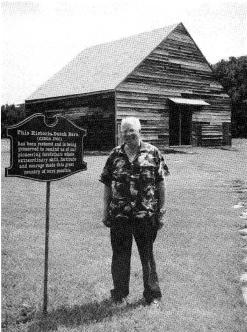

Vince Schaefer and the restored Larger

Wemp barn in Onesquethaw.

by Thomas Lanni

Only

five years ago I had the opportunity to attend a lecture at the

Atmospheric Sciences Research Center (ASRC) given by Vince Schaefer,

who was then Director Emeritus of ASRC. I was doing research at

ASRC for my PhD. in physics and had heard about this fellow who

had started the ASRC in the early 1960's with a group of colleagues

from the General Electric Research Lab. The corridors of ASRC contained

photos of Vince in the Rockies with high-schoolers enrolled in

his Environmental Studies Workshop, taken in the late 1960's. It

was with some preconceptions then that I sat and watched this big,

smiling bear of a man speak so plainly on a subject that he clearly

held dear to his heart. My surprise, at the time, came from :he

fact that Vince had chosen to hold forth, to this audience of scientists,

not on the atmosphere or environment, but on an eighteenth century

agricultural architectural form peculiar to the Hudson and Mohawk

river valleys and their environs, which he referred to as a Dutch

barn! Only

five years ago I had the opportunity to attend a lecture at the

Atmospheric Sciences Research Center (ASRC) given by Vince Schaefer,

who was then Director Emeritus of ASRC. I was doing research at

ASRC for my PhD. in physics and had heard about this fellow who

had started the ASRC in the early 1960's with a group of colleagues

from the General Electric Research Lab. The corridors of ASRC contained

photos of Vince in the Rockies with high-schoolers enrolled in

his Environmental Studies Workshop, taken in the late 1960's. It

was with some preconceptions then that I sat and watched this big,

smiling bear of a man speak so plainly on a subject that he clearly

held dear to his heart. My surprise, at the time, came from :he

fact that Vince had chosen to hold forth, to this audience of scientists,

not on the atmosphere or environment, but on an eighteenth century

agricultural architectural form peculiar to the Hudson and Mohawk

river valleys and their environs, which he referred to as a Dutch

barn!

After the talk I approached Vince because his words had evinced

in me, although not a particularly active student of history, certain

stirrings. At that time I happened to be living on an eighteenth

century Dutch farm, which happened to be located on the Onesquethaw

Creek, a tributary of the Hudson River. I relayed to Vince this

information, which seemed to delight him, and I explained that

none of our outbuildings seemed to conform to his descriptions,

although I would certainly investigate this further. Beaming from

ear to ear, Vince reiterated that these barns were somewhat rare

and sadly were disappearing from the landscape through disinterest

and neglect.

It was only later in our acquaintance that I came to understand

why Vince was smiling as he told of the plight of these once great

barns. He foresaw our meeting as an example of one of his favorite

intellectual processes, whereby an accidental or unintentional

happenstance brings about an insight or discovery of some kind.

This synthesis is called serendipity, after the Princes of Serendip,

who made a regular habit of such things. An important feature of

this phenomenon is that it is the open and prepared mind that most

often enjoys such "lucky" occasions. All that I have

learned about Vince's multifaceted career, and my own experience

with him, has convinced me that he was a true prince of Serendip,

not by birth, but by diligence in preparing his mind and by having

the confidence to follow the natural lead of his intuitions.

As I returned to my work after that first meeting with Vince there

was a certain sense of excitement, a feeling that I was involved

in some greater purpose, a feeling that would revisit me after

future conversations with Vince. Thus encouraged, I proceeded to

make inquiries in the neighborhood and at the library, and began

to learn much about the history of the area and of the farm where

I lived. Evidently there had been a Dutch barn on our farm that

was bulldozed in the 1950's by a previous misguided owner, and

there were others still standing in the vicinity, which I visited.

Other information that I acquired on these forays served to deepen

my appreciation of my local surroundings, and of the people, both

past and present, who had chosen to live there. When I told Vince

of my findings he immediately suggested that it would be a good

idea to try and find a barn that needed a good home and move it

to our farm. I transmitted the gist of this idea to Carl Touhey,

the Albany businessman who owned the farm, and he too became enthusiastic.

It was only a short time until Vince had convinced Carl to buy

and restore the endangered larger Wemp barn, one of the finest

Dutch barns still in existence.

As I was the caretaker on this farm and Mr. Touhey was often

away, I became the de facto supervisor of this project of dismantling,

restoring and reerecting this magnificent barn. Fortunately, we

had hired experienced contractors to do this work, but for me it

was a trial by fire and I learned a great deal about these structures

(and much else) that only a few months before I had never heard

of. The barn now stands proudly on the flats of the Onesquethaw,

is open as an educational museum to the public and school groups,

and is used by the community and the Dutch Barn Preservation Society

as a gathering place. Throughout the barn project Vince was there,

taking pictures, making suggestions, and a working relationship

and friendship developed between us. In the ensuing years I met

with Vince many times, and whether we talked of the environment,

or barns, or history, I always felt fortunate to have access to

his vast store of knowledge and experience. It was through Vince

that I became a Trustee and officer of the DBPS and I dare say

a true barn aficionado. This can be attested to by the fact that

I never travel without DBPS brochures and am loathe to pass by

any barn that looks like it may be a Dutch barn without stopping

to have a look. Like Vince I often go out my way to take an unknown

road in the hopes that a discovery may be made, as indeed some

have.

These memories of Vince serve to highlight a point about individuals

and organizations, about the future and the past, and about order

and chaos in this world. Vince Schaefer has died, and has left

an incredible legacy. There are the scientific discoveries, the

books and manuscripts, works of art in sculpture and photography,

and there are great barns that would not exist but for Vince. There

are organizations, the ASRC, the DBPS, the Van Epps Society, that

were formed around principles which he espoused and of whose importance

he was able to convince others. There are the people, his friends

and family, the many students and colleagues, and countless others

who were touched in some way by his kind and generous spirit. All

of these things and much more are here now for us to enjoy, as

Vince would have enjoined us to do. But I think he would also have

cautioned us about resting on his laurels, there is much work to

be done, many things to be learned, all that has been built up

is always subject to the inexorable ravages of entropy and time.

Also, I believe Vince would take us to task for ascribing this

vast legacy to him, he would no doubt remind us of all those who

came before him and who worked with him, and he would surely remind

us of the role of such unknown forces as serendipity and of God.

I suppose Vince would want us to celebrate his life by taking up

our responsibility for the world around us as he so aptly did,

and like him to be teachers by example to those who will follow

us in time. Vince is gone, but the intellectual curiosity and the

respect for nature and our history that characterized his life,

and that he fostered in so many of us, must be carried on...

The Trustees of the DBPS have seen fit to dedicate this issue

of the Newsletter to Vince Schaefer. He was a founding member of

the Society and a veritable guiding light in the workings of the

group since its inception. I know many others could recount stories

similar to the one above about how Vince influenced and inspired

their interest and dedication to the study and preservation of

Dutch barns. Vince will be missed, for his insight and his diligence

in lobbying for this cause and for the good humor and fun he brought

to group activities. We will all have to work a little harder if

we are to fill his shoes. So let this serve both as a tribute to

the individual, Vince, and his past endeavors, and an encouragement

to the group and a heralding of our future accomplishments.

Finally, we have chosen to include the following piece written

by Vince for the Miscellany in 1988. It is here not because it

is his greatest work, but because it clearly represents his views

on the preservation of Dutch barns.

The Future Existence of Dutch Barns in

the Northeast

by Vincent J. Schaefer

The Dutch barns of the Mohawk, Schoharie and Hudson Valleys

remain as one of the few tangible connections between the early

pioneer settlement of Eastern New York and the present era. These

areas were settled by the Holland Dutch, German Palatines and a

few Swedes starting in the early 1600's. The decline of the farm

economy in the Northeast is posing a rapidly cresting concern for

the future welfare of these unique structures. The distinctive

structural design of the Dutch barns reflects the tradition of

the Dutch and northern Europe homeland. These barns are essentially

replicas of those built in Holland in the early 1600's and earlier.

Nearly identical architecture can be seen in the few structures

remaining in Europe of that time period, including features also

present in homes of that era. Fortunately, some of our barns are

still used on a daily basis on working farms and so long as the

roofs remain leak free and fire is avoided, can persist so for

another century or more. Others are not so fortunate. Where originally

the Dutch barn was the dominant structure on a farm containing

from 40 to 100 acres or more, many of them are now surrounded by

single family homes, condominiums and even industrial structures.

As population pressure builds, the farm economy dwindles and real

estate developers plan, the future destiny of many of the remaining

Dutch barns becomes precarious at best. What should happen under

these circumstances? That is a hard question to answer.

As the old farmhouse is modernized, restored or destroyed, the

other farm buildings bulldozed, several things can happen to a

Dutch barn. If its roof has not been neglected, its timbers are

likely to be intact with their massive anchor beams, posts, purlin

plates, rafters and braces. Choice ones may even have their rafters

covered with a plank roof, wide boarded original siding, wooden

hinges on the large gable end wagon doors and Dutch iron hinges

on the animal doors. The early barns were obviously built by master builders

who apparently enjoyed working with the huge virgin pine and oak

trees available nearby. Not only were the timbers fashioned by

broad axe but many were finished by adze, the resulting surfaces

being so smooth and flat that they appear to have come from a planing

mill. Some of the massive anchor beams were even chamfered as giving

finishing touches to the timber. When such an intact barn is likely

to be detached from its original central role in the farm economy

there are several alternate uses available. If the developer has

a sense of propriety, a respect for local history, heritage and

posterity, he will use the barn as a central theme, respecting

its integrity and using it with as few modifications as possible

as a recreational and cultural center of his new development. A

second and less desirable alternative is to carefully dismantle

the barn, reerecting it somewhere else either as close as possible

to its original configuration or with as few modifications as possible.

This procedure is the one currently in favor. Such action has led

to the removal of a basic part of our local historical tradition.

It is a rare situation in which a barn is taken down without some

loss of its integrity when it is reerected. In most instances when

a barn is to become a "second home" or a studio for a

city dweller, drastic changes may be expected. While the timbers

may survive the dismantling and transportation activity, it is

likely that many, many more subtle features will disappear. Even

this however may be better use of these ancient structures than

to have them disappear by fire, rot, or under the blade of a bulldozer.

The ruin of a significant cultural

treasure: the Van Bergen Dutch barn of Leeds, Greene County,

New York.

I write with a degree of understanding of this rapidly developing

problem. In 1947, I bought what appeared to be a magnificent very

old Dutch barn which was apparently built in 1701 on one of the

original farms on the Great Flats adjacent to the pioneer village

of Schenectady, settled in 1661 by Arent Van Curler. This barn

was located on the western edge of a farm adjacent to a beautiful

cold spring. This barn was among the early ones erected on the

Great Flats and was built by or for Johannes Teller who had survived

the Schenectady Massacre of 1690. After I had bought the barn with

my hope in 1947 of eventually converting it into a museum, I discovered

that because of a long neglected roof covering, rot had become

established in the massive posts, the purlin plates and the long

roof rafters. At that time I could see no way I could possibly

replace these damaged timbers. Even today it would require a tremendous

effort and cost and the result would have questionable merit. Consequently,

I was forced to dismantle the barn, salvaging all of the sound

timbers, siding, doors and floor planking. I decided to see whether

I could take down the barn alone and eventually was successful

in doing so except for the massive posts and anchor beams. As the

dismantling process proceeded, I obtained a series of excellent

photographs of the barn structure and its simple but highly functional

design. From these photographs I have been able to construct an

accurate scale model of this barn at a reduction of 24 to 1. Thus

the finished model is 25 inches square and 21 inches high. The

lean-to on the northwestern side has an area which was originally

25 feet long and 10 feet wide.

As the field research of our Society proceeds, it becomes apparent

that there are probably at least 100 Dutch type barns still in

existence in 1988. At least half of them however face a very uncertain

future. Many of the better ones have been integrated into a barn

complex on working farms so that their pristine condition in many

cases ceases to exist. A few of these are still in excellent condition

after more than 200 years. Those facing an uncertain future range

from the few still in excellent condition to the majority which

are no longer being used effectively and face the distinct possibility

of neglect and eventual destruction from fire, rot, snow loading

and wind storm. Those which are in fairly good shape but without

a useful function are likely to be sold by the current owners to

the highest bidder. When this happens and the barn is removed our

region loses one of its most important linkages with the past.

At least a few of the best ones should be designated as National

Historic Landmarks, protected from further change and developed

into a formal part of our national heritage. In Switzerland, Sweden

and other European countries extensive collections of ancient structures

are accumulated, meticulously restored and perpetuated as outdoor

museums with government sponsorship and continuing support. In

America a few such assemblies have been established as tourist

attractions under private initiative. Perhaps this is the best

we can do.

Meanwhile we hope that our Dutch Barn Preservation Society can

raise public consciousness to appreciate the intrinsic value and

importance of these ancient structures so that they are better

appreciated by their owners as well as the general public. The

research minded members of the Society should bend every effort

to glean as much solid information as possible from the barns still

remaining. There are many fascinating questions about these Dutch

barns and great satisfaction to be had in obtaining the answers.

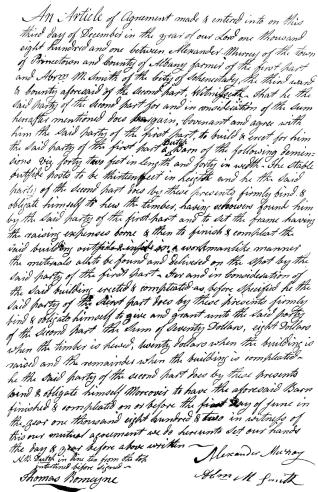

There are a number of interesting features in this barn contract.

First, it must be pointed out that in 1801, both the town and the

city of Schenectady were in Albany County. The builder, Abm. M.

Smith, was from the Third Ward, what is now Rotterdam. Perhaps

most important to us is the insertion of the word "Dutch" in

the description of the barn on line 10. Evidently this was enough

to specify exactly, even at this date, what sort of barn was to

be built. The dimensions that follow include only the perimeter

and the height of the stable outside wall posts. There is some

uncertainty about the word "schowers" (?) in line 14;

it does not seem to be Dutch, and by context appears to refer to

trees. The contract specifies that the barn is to be completed

in less than six month's time, for which the builder is to be paid

$8 for hewing the frame, $20 for raising, and $42 for completion,

a grand sum of seventy dollars!

Research

Finds: Contract for the Construction of a Dutch Barnfrom

the Collection of Donald A. Keffer, West Glenville.

|