|

Dutch Barn Preservation Society Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation NEWSLETTER

SPRING 2000 By Peter

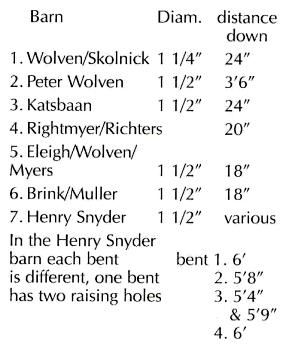

Sinclair Fitchen's strong interest in how the New World Dutch barn was raised led him to a number of speculations. In the end he felt that the columns of the H-bents were too weak for the raising holes to have served as lifting points. He speculated that the H-bent must be pulled up by two "three legged gins' with lines attached to the anchorbeam. He saw the function of the raising hole as having more to do with a support for scaffolding needed in the next major step in erecting the frame which was, lifting and joining the purlin plate to the columns and braces. During a cold January and February of 1982, Richard Babcock and his sons disassembled the three bay Oxburger Dutch barn in Guilderland, Albany County, New York (3). It was being replaced by a housing development. The crew used only jacks, levers, block and tackle, and a gin pole, to take down and disassemble the three bay frame. They re-erected it that spring at Phillipsburg Manor, an historic mill site restoration in Tarry town, Westchester County, New York. "Raising holes" and Their Probable Utilization, by John Fitchen, from The New World Dutch Barn, with permission of Syracuse University Press. Many of the columns in New York Dutch barns are pierced transversely by a hole - rarely by two holes, as at D, E, and F - which are located in the upper portion of the columns, one or more feet down from their tops. Nothing significant has been discovered remaining in any of these holes. However, this series of drawings shows examples of some of the levels at which the holes occur, together with a conjectural reconstruction of how they may have been utilized as scaffolding at the time of the purlin plate erection. In cooperation with John Harbour, the executive director at the site, and others of the staff, Babcock attempted to use traditional methods in raising the frame. With his friend Henry Suydan they built a bull wheel using the central shaft they had found in a barn in Schoharie County. The bull wheel, or windlass, was operated by two men and made the raising possible with a small crew. Babcock attached the lines of his gin pole to the anchorbeam, as Fitchen had thought was the place to lift, but he used only one gin pole. Fitchen had thought that two "three legged gins" would be necessary to lift the bent and set the stub tenons, at the foot of the columns, into the sills. Babcock knew from experience that this was not necessary. Today timber frames are raised using metal scaffolding and industrial cranes so that much of our early building technology is forgotten and difficult to recreate. Just before the final lift of the Hbents of the Phillipsburg barn, inc hand-a-half diameter shaved hardwood poles two foot long were inserted in the raising hole of each column and when the bent was upright these were used by the Babcocks, as Fitchen had suggested, to support scaffolding planks from which the crew then guided the purlin plate. Babcock demonstrated the feasibility of using wooden poles in the raising holes and a number of examples of wooded poles and fragments of them have been found in Dutch barns, but it should also be remembered that iron pins were used on hay barrack poles to support the roof and these iron bars might also have been used in the raising holes. Raising a 40- to 45-foot long purlin of a three-bay Dutch barn above the 16-foot columns, lowering and matching its ten mortises to the tenons of the four columns and six braces and driving pins in each joint takes lots of close, hands-on work. A platform set three to four feet below this action is ideal, but Fitchen realized, after looking at almost 80 Dutch barns, that raising holes are not always this conveniently placed. Often they are too close to the top of the column. Sometimes, frequently in Albany County, there are two holes. Two barns in Somerset County, New jersey have three raising holes in each column. In a study of seven Dutch barns in Saugerties, Ulster County, NY, the raising-holes were set the following distance down from the top of the purlin (4).

The variety of their placement on the columns suggests that multiple uses may have developed for raising holes. Some suggestions have been to support the axle for a sheave (grooved wheel) of a pulley system for assisting in raising the bents or to assist in twisting a warped column. Jack Sobon, in an unpublished 1990 "preliminary investigation" illustrates a number of possible uses for the holes to stabilize the bents or position the columns and braces for fitting the purilin (5). Raising Hole Use; Four Ideas from Jack Sobon. with permission of the architect. A. A pin for hoisting: This system would save a lot of rigging time. B. Temporary bracing for support and positioning: Planks could be pegged on the post prior to raising. When the bent was plumb the bottom of the plank could be nailed to the sill or pegged in a predetermined hole for temporary support. The drawing also shows a horizontal board that positions the columns and braces to receive the purlin. These planks and boards would be set as the frame parts were pre assembled on the barn floor during the scribe- rule process. C Staging with an upright: Sobon uses an idea he saw in a book to improve the safety of the scaffold. D. Gin Pole Mount: Another idea he saw in a book for raising the purlin plate. This is an excellent idea but would not work on later barns with dropped tie-beams. Chris Albright observed that the early barns in Guilderland, Albany County, did not have tie beams on the end walls but relied on rafter collar-ties to support the gable wall studs (7). This development is seen elsewhere. It is as if the rafter collar tie eventually became a dropped tie-beam as the barns' verdiepingh, column height above the anchorbeam, became taller with time. Karen Gross, from Breitenheim, Germany, has sent to the New World the first and perhaps only written and illustrated account of the existence and use of the raising hole in Holland. (This will be reviewed in a future "News Letter.") The information was collected from Dutch timber frame carpenters in the 1930s, about 300 years, I believe, after they introduced the raising hole into the New World. Hay Barracks were introduced at the same time as Dutch barns yet in 200 years of isolation the technology for raising the roofs of barracks was eventually quite different here. We still used the holes in the poles but changed from the European screw- to a "sweep and temple" lever-system. Holland eventually developed a cable and pulley system that was attached to the pole and raised all four corners at once. It does not use the holes. Endwall Bent, /Chapen 4-bay scribe-rule Dutch barn (Cia-i) Claverack, Columbia Co., NY This barn has unusual longitudinal raising holes near the tops of the columns on the end bents. It has a number of features found in the Schoharie Valley. The columns are rotated in the H-bent and they and the purlin are capped with an upper tie beam. This may represent an 18th century German influence although external H-bent upper tie beams were also used on the frame of the 1675 Jan Martense Schenk house reconstructed in the Brooklyn Museum. Raising holes are often found in the posts of the side walls of Dutch barns. Unlike, the raising holes in the columns these are longitudinal rather than transverse and suggest they were used in raising the side walls as a frame. Raising holes are generally not found on house frames nor on many of the small barns in Bergen County, New Jersey. The bents of these frames are lighter and it suggests that the holes might have assisted in lifting the frame but were not needed on the lighter house and barn frames. If the direction of the raising hole, longitudinal or transverse, indicates in what direction a frame or timber is raised, then the longitudinal raising holes in the end bents of an Otsego County Dutch barn, moved to the township of Claverack, Columbia County recently, Chapen (Cla-1), suggest the end anchorbeams, in that barn, were raised and supported on the door posts and the columns raised from the sides and joined to the anchorbeam and braces. Fitchen had conjectured such a system for raising a Dutch bent! but had thought the method took too much effort, especially for the internal bents. The end bents in this Otsego County frame have rotated columns and upper tie beams, an interesting construction feature found primarily in the Schoharie Valley. Raising holes on barn frames are found primarily in the Hudson! Schoharie and Mohawk valleys, and on Long Island, the historic region of the New World Dutch barn. Their use did not spread to other cultural areas but they continued to be used on the frames of later square-rule Dutch and side entrance barns and are found .in Ulster and Dutchess Counties even on mill-rule frames of the early 20th century. The raising hole is clearly part of the Dutch tradition that was not adopted by the American framing tradition that would come to dominate the 19th century throughout North America. In the northeast, American timber framing evolved from a mixture of New England and Hudson Valley Dutch scribe-rule traditions. American square-rule was invented in about 1790, and some think in New England (6), but its typical frame from Ohio to Maine includes three important New World Dutch features, the bent, the common rafter and the dropped tie beam. 1. John Fitchen, The New World Dutch Barn, A Study of its Characteristics, Its Structural System, and Its Probable Erectional Procedures, Syracuse University Press, 1968 2. John Fitchen, The Construction of Gothic Cathedrals; a Study of Medieval Vault erection, Oxford: Claredon Press, 1961; Phoenix Press, 1981; John Fitchen, Building Construction Before Mechanization, MIT Press, 1986. 3. Richard W. Babcock, Barns of Roots America, Babcock, 1989. 4. Peter Sinclair, The Raising Hole, unpublished Field Notes #4 of the Joy Farm Preservation Society, 1990. 5. Jack Sobon, Raising Holes; a Preliminary Investigation, unpublished, 1990. Greg Huber, Raising Holes; Unsolved Puzzle, Dutch Barn Research Journal, Volume 2, 1992. 6. There was a lively discussion on the origins of square rule at the 1997 annual meeting of The Traditional Timberframers Research and Advisory Group (TTRAG). A group within the Timber Framers Guild (TFG) with an ongoing interest in the development of American timberframing. 7. Chris Albright, The Two Barns of the Michael Frederick Farmstead, Guilderland, NY, Dutch Barn Preservation Society Newsletter, Fall 1996, Vol. 9, Issue 2. |