|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

Spring 1990, Volume 3, Issue 1

The

Tree Nail in Timber Framing of the Past

By John Fitchen

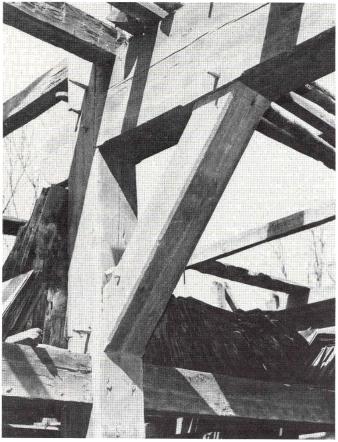

Some years ago, I was on hand to observe what was

scheduled to be a Dutch Barn demolition operation. It seems that

the farmer had decided that the barn was too old and decrepit to

serve his needs, so he was taking steps to remove it in one quick

effort. A heavy steel cable was secured to the barn's frame, the

other end of the cable fastened to a heavy-duty caterpillar tractor

with the intention of collapsing the structure by pulling it down

in line with its axis. The tractor's engine was revved up and put

in gear, whereupon the cable became rigidly and dangerously straight.

But the barn didn't budge. Instead, the tractor reared up in line

with the cable. So the project had to be abandoned for the ignominious

alternative of having the barn's joints, one by one, laboriously

sawn apart. If ever there was confirmation of the fact that the

use of tree nails could result in a permanently secure, unremittingly

durable structure, this was it.

Instead of using metal nails or spikes to secure the joints in

timber framing, the carpenters of the past relied on the time-honored,

long established tradition of tree-nails: that is, all wood connections.

Trenails (or treenails) were hardwood pins or pegs whose use involved

profound consequences. For example, unlike metal nails, the trenails

had to be individually prepared and shaped, one by one, and the

holes for their insertion, in turn, had to be bored separately,

one by one. Moreover - and this was the most inexorable requirement

- joining the members had to be done by mortice and tenon (or some

analagous device) which meant that they could not be butted together.

Rather, a tenon had to be fashioned at the end of a member, for

insertion into a matching mortice.

The Greater Wemp Barn, formerly located at Schoharie

Crossing, NY, exhibits the ends of hickory pegs (trenails) which

secure braces to post and anchorbeam. Rare chamfering is exhibited

on braces. Also rare is the shaping of the anchorbeam where the

brace enters. The barn has been removed from its site, but will

be re-erected in Albany County, NY. Photo by Clarke Blair.

In consequence of this additional length in the member, the sequence

of assemblage was irrevocably determined. A horizontal strut, for

example, between two studs, could never be framed after both studs

were in place, and this absolute, categorical situation came about

because the length of the strut was greater than the distance between

the studs due to the presence of the tenons at either end of it.

These modifications - shaping the tenons and voiding the mortices

- obviously required skilled work, and considerable time, to execute.

But they also influenced the

order and sequence of the framing process in an inescapable way.

For whereas a nailed strut can be inserted at any time between

two stationary studs, the all-wood scheme of timber framing imposed

a sequence of operations at the start. Thus, with only one stud

in place, a tenon of the strut had to be inserted in that stud's

mortice before the other stud could be maneuvered into place so

as to engage the tenon at the strut's other end.

Consequently, compared to

the rapidity and off-hand ease of nailed attachment, pegged joints

required both time and precision in executing them. The holes

had to be laboriously bored by hand, using such tools as augurs

or wimbrels. And since the purpose of the pegs was that of achieving

a secure, permanent attachment of the two members, there had

to be some means by which the peg would not work out of the hole,

either due to shrinkage or to any movement due to vibration or

other stress in the joint. Where any such action was not expected

to be a problem, smoothly shaped pins were carefully hewn to

fit snugly into the hole. But wherever such action was anticipated,

a different procedure was adopted.

Obviously, the holes bored

to receive the pins (the trenails) were necessarily and inevitably

cylindrical, but the pins themselves were not. They were never

turned out on a lathe (as some wheel spokes and slender balusters

might have been, and modern dowels invariably are). Instead,

they were painstakingly shaped by hand, usually employing the

tool called a drawknife. The shaping operation that resulted

from the use of this tool quite naturally caused the pin to be

octagonal instead of circular in cross section. The longitudinal

edges - the arrises - made the pin oversized with respect to

the hole; consequently, it could not be slipped in and out but

had to be forced into the hole. This feature was intentional

and welcome, for the arrises bit into the sides of the hole,

preventing the pin from becoming loose and indeed resisting any

attempts to withdraw it subsequently. The joint, so fashioned,

was made permanently secure, thanks to the circle of longitudinal "teeth"

biting into the sides of the hole.

An extreme case of this gripping

function of the arrises of octagonally hewn tree-nails is to

be found in the thick planking of the floor of the Deertz Barn.

The jarring, pounding and bouncing effect of horse's hooves,

and of the heavily-laden hay wagons in season, had to

be positively guarded against at all costs. So here, astonishingly,

square pegs were driven into round holes. Obviously, this could

be done only by a heavy maul in the hands of a strong and particularly

adept worker. For, once driven home, or even perhaps split or

smashed in the process, there was no way in which the pin could

be drawn out; the hole would have had to be bored anew. The pegs,

bluntly tapered just enough at the entering end for them to be

firmly positioned upright in the hole, were square in section,

with sides the same dimension as the diameter of the hole. Since

both peg and flooring were of oak, it obviously took considerable

force to drive the pegs all the way in, but, once in, they were

there for the duration.

It should be recognized that, even where the craftsmanship was

of the highest quality, there were instances of the use of smoothly

cylindrical pins, or at least ones having long tapered points without

arrises. Such pegs were commonly used, temporarily, in the procedure

of test-assembling a timber framework before its final, permanent

consolidation. This requirement was an essential concomitant in

barn building, for example, where the columns had to conform to

both longitudinal and transverse linkages in the ensemble. Here,

in the double test-assemblage operations, the pins had to be quickly

and easily withdrawable, and hence without any gripping arrises.

In these two test assemblages-when first one and then the other

of the longitudinal and transverse test assemblages were involved

- the provisional pins were usually tapered, and they were invariably

made longer than the combined thickness of the two timbers they

penetrated. This extra length of the provisional pins meant that,

when driven into their holes, their smaller ends projected well

beyond the far side of the hole that accommodated them. This was

done in order that the pins might easily and quickly be removed

by tapping them out from their pointed ends.

Another and much less frequent instance in which smoothly contoured

pins were sometimes installed - permanently, this time - was in

situations where they were used to assure a very tight fit against

gapping at the joint, such as where the drawing apart or opening

up of the joint due to shrinkage had to be permanently and strongly

guarded against. Here, instead of boring the hole for the trenail

straight through both members of the connection at once (which

was the customary procedure), the hole, was bored through both

sides of the mortice, then separately and slightly off-set, through

the tenon. In this situation, when the two timbers were brought

together-when their mortice and tenon were linked - the hole through

them was unaligned. Hence, driving the tapered pin into and through

its hole caused it to exert great and continuous pressure in squeezing

the two timbers together at their joint.

The gripping function of the wooden pins' arrises is similar

to what happens in the case of metal nails which, in being driven

into the wood, force its fibers apart and thereby unite wood and

metal in a tenacious, permanent grip.

The degree to which precision was required in shaping the trenails

was augmented by a comparable handicrafted individualism existing

in the very tools of the carpenters in former times. Although the

bits of augur or wimbrel might be nominally of the same diameter,

these tools were not manufactured in a factory in innumerable replicas

but were forged individually. Consequently, in a sizeable undertaking

such as constructing a massive barn, the team of men assembled

to construct the project might include a number of carpenters,

each with his own kit of tools. The fact that their individual

augurs might vary even slightly in diameter meant that those assigned

to prepare the pegs had to be meticulously precise in shaping them-particularly

the smooth ones - in order that they might fit snugly into the

holes bored for them. No wonder that today" one occasionally

comes upon a smoothly contoured pin that is loose in its hole.

The foregoing comments go far to account for the universality

of the trenail as the essential unit in timber framing throughout

the past. It was essentially a handicrafted feature in which the

quality of performance was explicitly controlled at every step

of the procedure. When metal nailing eventually became universal,

the latter's rapidity of execution made the trenail and its not

inconsiderable advantages obsolete. But we can be deeply impressed

with the quality and integrity of the heritage of its surviving

achievements.

John Fitchen, architect and formerly Professor

of Fine Arts at Colgate University, authored the book The New

World Dutch Barn: A Study of its Characteristics, Its Structural

System, and Its Probable Erectional Procedures (Syracuse

University Press, 1968).

If A Barn Could Talk

By Everett Rau

I am an Albany County Dutch barn. I was proud more

than two hundred years ago when the last pine shingle was put in

place on my roof and the last ironwood sapling was laid across

my anchor beams - to support a bumper crop of tall rye that had

been cradled and bound by the steady hands of the Ogsbury family.

<-

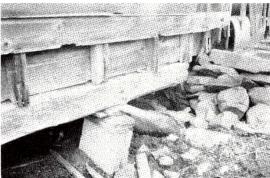

The west sill of the Ogsbury barn awaits repair.Photo by

Everett Rau. <-

The west sill of the Ogsbury barn awaits repair.Photo by

Everett Rau.

My wood shingles have long since decayed. Some kind owner put

some black tar paper on my roof to keep it from leaking; this also

aged and before many years needed repair. Seems farmers don't always

have ready cash, but finally, in the year 1929, Ev Rau's brother

Raymond, working for General Electric, had the money to put galvanized

steel roofing over that tarpaper on my roof.

In those years of the 1920's and 1930's, when Ev Rau was a boy,

laughing men filled me with loose hay in June and July. In November,

the traveling baler came, and then the cash crop was sold. But

farm prices over the years did not keep up with industry's wages;

no longer did I hear laughter in summer and fall and seldom did

any person come near. Yet I remember that in 1932 or 1933, men

jacked up my main posts, the supports for my big anchor beams.

They put some flat stones back under my sills, already half decayed.

But my owners forgot to keep watching for the frost action on my

foundation. Every year, my stone supports slipped away. Maybe Ev

Rau cared for me, but he was raising a family and working away

from home. He did not see the slow settling of one anchor beam

post (rotting was going on down below) or see my purl in plate

bend sharply, dropping down 10 or 11 inches. Nor did he notice

my sills were gone.

Years passed. Finally, Ev Rau retired and was back on the farm.

One day Mark Hesler asked him to join the Dutch Barn Preservation

Society. Ev had not thought about the historic value of his Dutch

barn until he took a Dutch barn tour and listened to visitors talking

about how once there were many old barns but how now they were

rapidly disappearing. Ev met Vince, Jack, Chris, Shirley and the

others. These people were concerned about saving Dutch barns. That

did it. The very next day, "Doctor"

Ev started looking at me to see what needed fixing.

Well, the good thing was that over the years I managed to keep

fairly dry because of my metal roof. But, even so, my purlin was

bent and cracked, my sills were gone, except for the section under

the granary, and I was eight inches out of level. My roof was sagging

due to my bent purlin plate. My doors were off or rotten on the

bottom. My flooring had been two inches thick, but it was rotten

four feet in from the doors. My floor supports were broken from

heavy tractor loads. My south siding was weathered by the sun until

it looked like a screen.

Soon Ev was digging under my anchor beam support posts with a

shovel and bar and a come-along. Some old stones were removed.

They were big, and they had been tipped sideways by settling. Ev

dug around them and poured concrete into the 40"deep hole

he had made. Two weeks passed. I thought I was forgotten again,

but one day I felt my bent purl in being gently raised by a hydraulic

jack. The plan was to jack up 2" that day and 2" the

next day, and so on until my purlin plate was straight.

My east sill once was 42'-3" long. Now it was rotted out.

To replace it, Ev cut one out that long, 9" by 10" thick,

with a chain saw. There is more to come. The west sill will be

sawed on our sawmill after Ev extends the carriage to support the

42' length. Now I have cement piers, four on each side. I'm not

level yet, but I look better. My door frame had an old notch on

top for a center pole for the two doors that used to swing there

in the opening. Maybe Ev will make a new set of wooden hinges like

I used to have. Maybe someday he will replace the hay barrack that

stood beside me. He knows that farmers still used them when I was

built.

If I could speak, I would shout "Hurray!" for the people

in the Dutch Barn Preservation Society. But for them, I would have

to yield to the forces of nature - wind, rain, rot, ants, and,

finally, gravity.

Thanks to repair by Ev and the others, I can live on as a monument

to early settlers who braved the wilderness and endured many hardships

to start this farm. I knew those who fought to be free in the Revolutionary

War and others who went to the Civil War. Those families, and the

workers whose names are written on my timbers, "made it happen" for

you today. I hear you people are coming to measure and study me.

I'll be looking for you. Keep up the good work.

The author, Everett Rau, resides on his family

farm near Altamont, NY.

Spring

1990 Newsletter, Part Two

|