|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

Spring 1992, Vol. 5., Issue 1

By Roderic

H. Blackburn with contributions by Willis Barshied, Jaap Schipper

and Anthony Sassi.

AUTHOR'S

NOTE: Objects associated with Dutch farming practices in New

York and New jersey have not yet received much attention in easily

obtainable publications. The present article is a preliminary

effort to document objects which are distinctively Dutch.

Dutch Farming

"The wheat flour of Albany is reckoned the best in all North

America, except that from Sopus (Esopus) or King's Town (Kingston)".(1)

From this observation Peter Kalm, a Swedish naturalist traveling

through New York in 1750, derived the nature of Dutch agriculture.

Dutch farming was commercial, producing primarily wheat but also

corn and rye for sale. Oats were raised for horses, and flax and

hemp were sown for home consumption. Large orchards produced primarily

apples - peaches and pears being unsuccessful. Potatoes were planted

by almost everyone and peas, like wheat, were produced in great

quantities and shipped to New York. Cows, horses, pigs, sheep,

chickens and geese were kept in numbers only sufficient for domestic

use. A prosperous farm, however, was by modern standards well populated

with the owner's children, other relatives, hired hands and slaves

who, in all, could number as high as two dozen persons.

Farm Structures

The farm of Martin Van Bergen in Greene County, depicted in John

Heaton's overmantel painting of ca. 1733 (DBPS Newsletter, Fall

1989), proudly declares these many farm residents (plus two Indians)

and the principal structures of a farm - the house, a three-aisled

Dutch barn, two six-post hay barracks, a blacksmith shop, and a

gate with fencing.

What it doesn't show are other common structures, the great number

of farm implements and tools, and the crops. Indeed the only indication

of crops in the painting comes from the well-filled hay barracks

(used for unthreshed grain as well as hay for the stock) and the

bags of flour in the Dutch-style wagon.

Other farms had additional structures. Some had a small one-aisled

barn of Dutch construction, in one inventory referred to as a carriage

barn, now rarely seen.(2) A corn crib, also rare today, must have

been a fixture on those farms which grew the quantities of corn

observed by Peter Kalm in the mid-eighteenth century.(3) Sheep

appear in the Van Bergen painting and presumably may have either

lived in the large barn or had their own sheep fold, though inventories

appear mute on this fixture. Presumably a pigsty had been built.

I have been told of one which once survived,(4) but on this structure

inventories are almost mute, excepting one in 1643 of a farm called

Vredendael which included a hog pen. That inventory also included

a cook house, a few examples of which still exist, sometimes confused

with smaller structures which were more commonly called and used

as smoke houses. In the Van Bergen painting is a single slant roof

shed identified in documents as the forge. The simplicity of its

construction suggests it is a type which could be used for other

purposes. One such early structure exists just south of Amsterdam

in the Mohawk Valley.(5) Another 1643 inventory, of the farm called

Emmaus (widow of Jonas Bronk between the Harlem and the Bronx Rivers

in what is now Morrisania), lists a tobacco house. None of these

survive in New York or New Jersey but in the Netherlands they were

long single aisle structures.(6) Sheepcotes were mentioned by Kiliaen

Van Rensselaer in 1634.(7) No doubt there were other specialized

structures on some farms, though inventories focus almost exclusively

on hay barracks, barn and house.

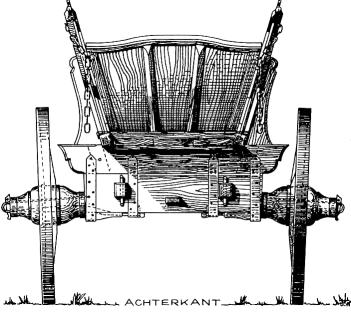

Hay Wagon of the Province of Friesland,

the Netherlands (end view).

From H. G. Fokkers,

Het Wagegenmakerbedrijf

in Friesland (1979)

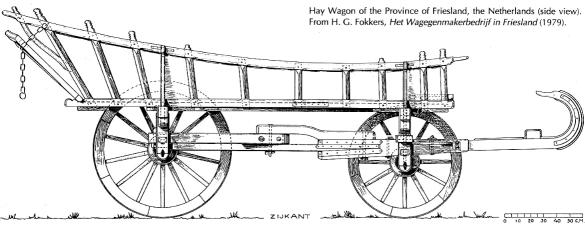

Hay Wagon of the Province of Friesland, the Netherlands

(side view). From H. G. Fokkers, Het Wagegenmakerbedrijf in Friesland

(1979).

Farm Objects

The complexity of a Dutch farm, however:-, is more. strikingly

revealed in the wide variety of vehicles, containers, tools, and

implements which appear in inventories. A sampling was taken of

ten inventories of farms associated with Dutch names,dating from

1643 to 1773.(8) Two points are most striking about these inventories:

farms; had far greater variety of objects in the latter period,

yet the objects which occurred early on persisted without apparent

change to the end. Dutch farms, and presumably farm practices,

did not change in type; just in complexity.

The following is an example of an inventory:

"September 27, 1643 Inventory of the farm Vredendael, [near Manhattan]

owned by a Mr. La Montagne, leased to Bout Frances. The farmhouse, barn, a

barrack of four posts, cook house and hog pen. 1 wagon, near new; a foot plow

with appurtenances, in working order; 1 ditto iron harrow; 1 three-pronged

fork; 1 two-pronged fork; rope harness for two horses in good condition; 1

fan; 1 peck measure bound with iron; 1 iron bound churn; 2 milk tubs; 1 butter

tub; 1 new tub holding one half hogshead; 1 water pail; 1 oak chest; 3 good

scythes with snaths; 3 Flemish scythes, good and bad; 2 handles; 3 pickaxes,

one of English make; 1 hand cross-cut saw; 1 iron wedge; 1 buttermilk tub;

1 half barrel with a brass faucet; 1 herring barrel; 4 ferrules for scythe

blades; 4 ditto for Flemish scythes; 4 mattocks; 2 bill hooks; 2 new axes;

1 currycomb; 1 iron ladle to melt lead; 1 pewter tankard; 1 pewter mug; 1 large

pewter basin; 1 ditto platter; copper kettle; 1 grindstone; 1 wheelbarrow;

1 25-rung ladder; 2 millstones, dressed and grooved; 1 jackscrew for the hay

barrack; 1 auger; 1 carpenter's adze; 1 pruning knife; 1 hand saw; 1 trowel,

2 bits; 2 ferrules for a wooden maul; 1 gun; 1 iron bolt, 1 1/2 feet long." (9)

Distinctive Dutch Objects

Judging by contemporary accounts, usually written by

English speakers unfamiliar with Dutch life, certain objects on

Dutch farms were distinctive to this ethnic group. Those accounts

describe the Dutch style of wagon, the Dutch hog plow, and the

Dutch use of the sith and mathook. Other less visible objects,

or design or decorative features of objects, are also distinctly

Dutch but did not catch the eye of these observers from the outside.

Additional objects may be thought of as representative of Dutch

farms even though they are not distinctly Dutch in form or function.

Here is a brief discussion of some of these.

The Dutch Wagon

No Dutch wagon, complete with body, undercarriage, and

wheels, has yet been found although several bodies which appear

to be from Dutch wagons have been located. No more complete discussion

of the appearance and utility of this vehicle matches that given

by Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, describing life on his farm in

Orange County, New York, in the 1760s.

"You have often admired our two horse wagons. They are extremely

well-contrived and executed with a great deal of skill; and they

answer with ease and dispatch all the purposes of the farm. A well-built

wagon, when loaded, will turn in a very few feet more than its

length, which is 16 feet, including the length of the tongue. We

have room in what is called their bodies to carry five barrels

of flour. We commonly put in them a ton of hay, and often more....

We can carry 25 green oak rails, two-thirds of a cord of wood,

3,000 pounds of dung. In short, there is no operation that ought

to be performed on a farm but what is easily accomplished with

one of these. We can lengthen them as we please, and bring home

the body of a tree 20 or 30 feet long. We commonly carry with them

thirty bushels of wheat and at 60 pounds to the bushel this makes

a weight of 1800 pounds, with which we can go 40 miles a day with

two horses..."

(10)

"On a Sunday it becomes the family coach. We then take off

the common, plain sides and fix on it others which are handsomely

painted. The after-part, on which either our name or ciphers are

delineated, hangs back suspended by seat chains. If it rains, flat

hoops made on purpose are placed in mortises, and painted cloth

is spread and tied over the whole. Thus equipped, the master of

the family can carry six persons either to church or to meetings.

When the roads are good we can easily travel seven miles an hour.

In order to prevent too great shaking, our seats are suspended

on wooden springs - a simple but very useful mechanism.

These inventions and neatness we owe to the original Dutch settlers....

The Dutch build them with timber which has been previously three

years under water and then gradually seasoned."(11)

Young Alexander Coventry, hauling materials to build his house,

was equally impressed with what a Dutch wagon could carry. He wrote

in his Columbia County diary on October 13, 1786, "Set out

with 2 wagons... [and a] cart, for Kinderhook after the boards,

bought there when coming from Albany. The 2 wagons took 1000 feet,

contained in 70 boards, and Howe's cart took 185 feet contained

in 57 boards." (12)

A thousand board feet of pine, at about 30 pounds per cubic feet,

would equal 1250 pounds in each wagon, far less than what, de Crevecoeur

ascribed to these wagons, yet still more than what modern automobiles

carry. Assuming they were about a foot wide, 70 boards would have

had an average length of 14 feet. The two-wheeled cart, on the

other hand, carried boards of an average length of just 3 1/4 feet,

pointing out the great versatility of the wagon for carrying long

loads. Carts are mentioned less frequently than wagons in inventories

and no early image or surviving cart is known. Functionally they

were useful for hauling heavy materials more easily unloaded by

dumping, while a wagon was better suited to hauling lighter but

bulkier materials like loose hay, bagged grain and produce, lumber,

and people.

More the measure of the writer than the observed were Strickland's

comments on Dutch wagons, and their loads as he saw them in 1794-5.

"No man is to be seen here on horseback, all people travelling

in waggons drawn by two horses abreast. . . The people sit on

benches going across the wagon, which has in general no awning

or covering. A fat Dutchman and his wife, and two or three clumsy

sons and daughters may frequently be seen thus driven and jolted

by a not less fat negroe Slave."(13)

The Dutch wagon was appreciated by the English who adopted the

form when Dutchmen came to East Anglia in the sixteenth century

to drain the Fens. Many of the regional varieties of English wagons

show a debt to this borrowing. In New Netherland, wagons are mentioned

in records from at least the 1630s. They continued in use into

the early nineteenth century. As with other examples of surviving

Dutch material culture, this early style wagon may have been used

until the Civil War in the conservative Mohawk Valley.

The Dutch Plow

The antecedents of the Dutch plow can be found in illuminated

manuscripts at least 500 years old where, for example, the use

of the wheel at the front of the plow is evident. Surviving wheel

plows in the Netherlands show that they were used in all provinces

until the present century.(14) While the wheel plow is thought

of as being characteristically Dutch, it occurred elsewhere in

northern Europe, and in the Netherlands plows without wheels were

also commonly used.

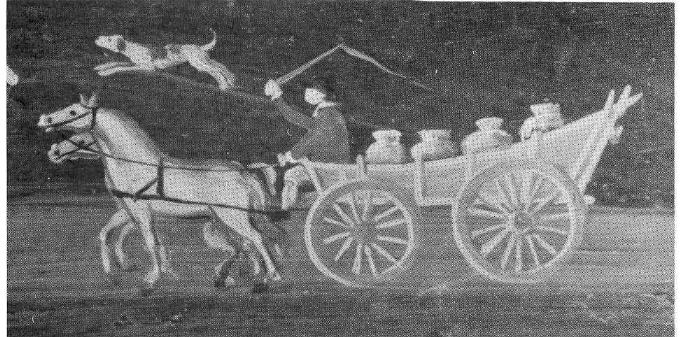

Dutch wagon with four bags, probably of grain.

Detail of the painting of the Marten Van Bergen Farm, ca. 1733,

at what is now Leeds, Greene County, New York. Collection of

the New York State Historical Association, Cooperstown, New York.

The Netherlands origin of the plow favored by the Dutch of New

York and New Jersey is, to be found in the province of Zealand

in the Netherlands and in neighboring provinces of Belgium.(15)

The American Dutch plow is defined by a number of characteristics:

a single handle, a pyramidal shaped iron share which cut the soil,

a wood moldboard which turned the soil over, and, in some cases,

the use of either a "foot" or wheels which gave stability

to the fore-end of the plow and regulated the angle and depth at

which the plow share cut the soil. Only a few such early Dutch

plows have survived displaying these features.(16)

The simplest of these is the swing plow variant which needed

no wheels or foot to support the end of the beam. At various times

during the period of its use it was called the Dutch or hog plough.

It was widely adopted by the Germans, Canadians and even Yankees

in Connecticut, the latter calling it the Dagon plow and exporting

it to the South.

Elsewhere especially in New England, a different kind of plow

was used (though in origin it too came from the Dutch). De Crevecoeur

deftly contrasts the Dutch plow with the English bull plow: . .

"Our next most useful implement is the plough. Of these

we have various sorts, according to the soil we have to till.

First, is the large two handled plough with an English lock and

coulter locked in its point. This is drawn by either four or

six oxen and serves for rooty, stony land. This is drawn sometimes

by two oxen and three horses. (Second) the one-handled plough

is the most common on all level soils. It is drawn either by

two or by three horses abreast, and when the ground is both level

and swarded we commonly put upon these a Dutch lock, by far the

best for turning up, and the easiest draft for, the horse."(17)

While the basic Dutch pyramidal share plow was adopted in some

other areas, its other distinctive features - the single handle

and the wheel or foot - were not favored outside of eastern New

York and north New Jersey. Here it persisted to the Civil War in

some more remote places, only giving way reluctantly to a wide

range of new-style manufactured plows - including some with wheels.

A partial explanation has to do with its construction. The Dutch

plow was lighter in construction than the New England bull plow,

reflecting its use in the softer soils of New York. New Englanders

had to contend with rocks, so the bull plow was pulled by a team

of stronger but slower oxen and was built heavier. The Dutch plow

was better at turning sod and soil at a fast clip when harnessed

to two horses (the swing plow) or three (the wheel plow).

"They use wheeled Plows mostly with 3 horses abreast & plow

and harrow sometimes on a full Trot, a Boy sitting on one Horse."

(Richard Smith, 1769) (18)

Smith's comment seems improbable, but others, like de Crevecoeur,

confirm that in the right soil the pyramidal plow cut the ground

with greater ease than the bull plow. Despite this J. Doucher,

brought up in the Hudson Valley, observed, "As early as the

year 1806, when I was but a lad, I began to observe the difference

in the construction of the plow. At that time there were two kinds

in use: one was the Hog plow, which was said to be of Dutch origin,

and another called the Bull plow, a Yankee invention...The Bull

was the most esteemed, the other went out of use about the year

1809 or 10".(19)

Author and researcher Roderic Blackburn has previously

written an informative article about the characteristic Dutch

hay barrack, also part of the unique early Dutch-American farm

scene, for this newsletter.

This article will be continued in the Fall, 1992 Newsletter. The

Dutch sith and mathook, schepel, and puzzling pieces of harness

will be featured.

ENDNOTES

1. (1749-50) Kalm, Peter, Travels in North America. New York:

1964, p. 335-6.

2. Two at the Johannes Van Alen Farm on School House Road in

Stuyvesant, Columbia County; one at the Ten Broeck Mansion in Albany.

3. One at the Johannes Van Alen Farm, Stuyvesant, N.Y.

4. Personal communication, Donald Carpentier.

5. Ditto.

6. Drawings courtesy of Jaap Schipper, Amsterdam.

7. Van Laer, A. J. F., Van Rensselaer-Bowier Manuscripts.

Albany: University of the State of New York, 1908, p. 204. Ibid,

p. 308.

8. These inventories are contained in the New York State Library's

Manuscripts and Special Collections: New York Historical Manuscripts:

Dutch.

9. New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch V.l1 p.134-5).

10. de Crevecoeur, Hector St. John. Sketches of Eighteenth

Century America. Edited by Henri L. Bourdin, Ralph H. Gabriel,

and Stanley T. Williams. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1925.

p.138-139.

11. cited in: Blackburn, Roderic H., "The Persistence of

Dutch Culture: A First Person Account of Building a Farm in 1787" in A

Beautiful and Fruitful Place, Selected Rensselaerwijck Seminar

Papers. The New Netherland Project, Albany. 1991 p.40.

12. William Strickland, Journal of a Tour in the United States

of America 1794-1795, New York: New-York Historical Society,

1971. p.74.

13. Vince, John. Discovering Carts and Wagons. Ayelsbury:

Shire Publications Ltd., 1978. p.17.

14. van der Poel, J. M. G. Oude Netherlandse Ploegen,

Arnhem: Rijksmuseum voor Volkskunde, 1967. p.19-65.

15. Cousins, Peter H. Hog Plow and Sith, Cultural Aspects

of Early Agricultural Technology, Dearborn: Greenfield Village

and Henry Ford Museum, 1973. p.4.

16. Examples can be seen at the Farmers Museum, Cooperstown,

NY; Daniel Parrish Witter Agricultural Museum, Syracuse, NY; Hadley

Farm Museum, Hadley, MA; Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, MI; New York

State Museum, Albany, NY; Ontario Science Center, Ontario, Canada;

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Upper Canada Village,

Ont.; and the Monmouth Country Historical Society, Freehold, NJ.

17. de Crevecoeur, Hector St. john. Sketches of Eighteenth Century

America, 139-40.

18. Smith, Richard, A Tour of Four Great Rivers / the Hudson,

Mohawk, Susquehanna and Delaware in 1769 / Being the journal

of Richard Smith of Burlington, New Jersey, Edited by Francis

W. Halsey, Port Washington, New York: Ira J. Friedman, 1964.

p.21.

19. J. Dutcher to T. B. Wakeman, quoted in Transactions of the

New York State Agricultural Society 27, pt. 1 (1867), p.474-5.

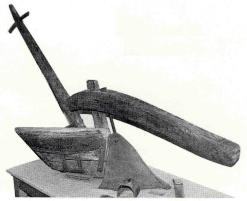

Apparently a Dutch swing plow, since an attachment

point for either wheels or a foot does not appear. Collection,

Margaret Reaney Library and Museum, St. Johnsville. Photo by

Clarke Blair.

|