|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER

Spring 1993, Vol., 6, Issue 1

A

Tale of Two Barns

by John R. Stevens

Photos are by the author unless noted.

In June, 1967 the writer commenced working as an architectural

historian at Old Bethpage Village Restoration on Long Island. This

museum village project had been started a few years earlier by

the Nassau County Museum. He was immediately confronted with a

daunting project - the restoration planning for the Minne Schenck

House, built c.1730 at what later became Manhasset, on the north

shore of Long Island, which was moved to the Restoration. This

Dutch - American house represented a building heritage with which

the writer was largely unfamiliar, although in 1964 he had surveyed

a house at Granville Ferry, Nova Scotia which he later realized

was of Dutch ancestry. This latter house had been built, he found

out, by a New York Loyalist named Amberman, who may have come from

Long Island. There had been a barn at the Nova Scotia site, an

interior photograph of which the writer later obtained, showing

anchor beam construction with extended wedged tenons. In 1964 the

Nova Scotia house was believed to be of French origin, and to date

to the early 1700's!

The writer found the literature about Dutch-American buildings

was exceedingly scanty. There was little written about them except

several picture books of Hudson Valley houses and the largely genealogical

books by Helen Reynolds and Rosalie Fellows Bailey, the first covering

the Hudson Valley and the latter western Long Island, Staten Island,

Rockland County and areas of Dutch settlement in New Jersey. These

books were published by the Holland Society in 1929 and 1934 respectively.

To develop an understanding of the Dutch-American building tradition

so that the Minne Schenck house could be accurately restored, the

writer commenced an intensive study of the construction details,

molding profiles, and so on, of many of the houses covered in the

Reynolds and Bailey books. Other houses of considerable interest

were found along the way that added much to his knowledge.

As time permitted over a period of years, field trips were made

to areas where houses of Dutch ancestry could be found. Houses

were measured and photographed and this information was a great

assistance in the restoration of the Schenck house.

The Van Nastrand-Rattkamp Barn standing

at Elmant, an the Hempstead Turnpike, in 1967.

Through the course of his studies the writer inevitably became

aware of the special kind of barn that was characteristic of the

areas of Dutch settlement. Helping him in this direction was Darrell

Henning, the curator concerned with agricultural interpretation

for the Nassau County Museum. Darrell had studied the few Dutch

barns that had survived on Long Island in some detail, and his

knowledge stimulated the writer to an interest in them. One of

the finest of the Long Island barns was the four-bay Van Nostrand

barn which was located on the north side of Hempstead Turnpike

(Route 24) in Elmont, about a mile east of the New York City line.

It was owned by a farmer named Rottkamp and used for agricultural

purposes. This barn would make an excellent addition to the Schenck

house site at Old Bethpage Village Restoration. A large barn, presumably

of Dutch type, was known to have existed at the original site of

the Schenck house at Manhasset. Regrettably, the Van Nostrand barn

was not available at that time, not was it to be in the foreseeable

future.

On July 6, 1968, while driving from Cooperstown to New York on

Route 20, the writer noticed, on the north side of the highway

a short distance west of Carlisle, a rather dilapidated barn very

similar in size and shape to the Van Nostrand barn. An inspection

of its interior revealed a fine Dutch frame, again similar to that

of the Van Nostrand barn, in excellent condition. A year later,

the writer purchased a copy of the late Dr. John Fitchen's 1968

book, The New World Dutch Barn (Syracuse University Press),

which, in addition to opening a new vista on the number and variety

of surviving Dutch barns, illustrated the barn he had seen, and

identified it as the "East of Sharon" barn. (Fitchen,

No. 33; drawings 4G, 5G, 17C; plates I, 2, 31-33) Inquiries made

in the area elicited the information that the barn was owned by

Mr. Walter Quackenbush. The writer informed Mr. Edward Smits, the

Director of the Nassau County Museum, about the barn and recommended

its acquisition for the Schenck house site inasmuch as it seemed

unlikely that a Long Island Dutch barn would become available.

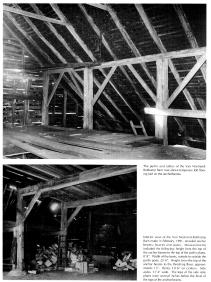

The East of Sharon Barn on its site

west of Carlisle in 1969. It measured 45 feet in width and 40

feet in depth. The ridge ran the shorter distance, in a north-south

orientation. Photo by Charles Tichy.

Mr. Quackenbush was contacted and agreed to donate his barn to

the Museum. It was dismantled by the Old Bethpage Village carpentry

crew and moved to Long Island in September, 1969. It was re-erected

in 1971, a number of the bents being raised by the E.W. Howell

construction crew on May 14 on the occasion of the annual meeting

of the Early American Industries Association which was held at

the Old Bethpage Village Restoration site. Work on the barn was

completed in August, 1971 except for the installation of the hinges

on the large doors. The west gable (south gable on its original

site) was unfortunately struck twice by lightning before lightning

arrestors were installed.

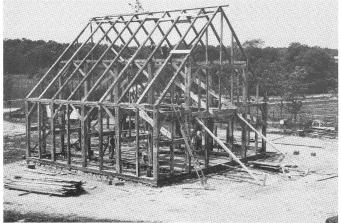

The frame of the Schenck-East of Sharon Barn after

reconstruction at Bethpage Village Restoration, June, 1971.

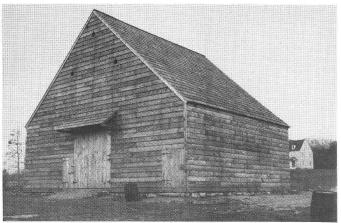

The completed Schenck-East of Sharon Barn at Bethpage

Village Restoration, December, 1971.

Over the years, the writer occasionally passed the Van Nostrand

barn, which continued in agricultural use and appeared to be well-maintained.

Then in January, 1991, Mr. Smits requested that the writer inspect

the barn and evaluate its condition. The Rottkamps had no further

use for it and the land it sat upon had considerable commercial

value. The writer took advantage of the opportunity to measure

and photograph it so that it could be drawn up for inclusion in

a proposed book on Dutch-American buildings. He stressed to the

museum director the importance of this fine building, which he

considered to be the finest Dutch-American building standing on

its original site on Long Island east of the New York City line.

To save it meant that it would have to be dismantled and moved

to another site. One possibility was that it be taken to Old Bethpage

Restoration and set on the foundation of the Schenck barn, formerly

the "East of Sharon" barn. The latter would be disassembled

and offered for sale. Alternatively, even if the Van Nostrand barn

could not be brought to the Old Bethpage Village site, there were

two other sites where a Dutch barn would be an appropriate addition.

One of these was the Queens County Farm Museum, with its c.1770

Adriance house, located only two-and-a-half miles north of the

barn's site. Another possibility was the Pieter Wyckoff house site

in Brooklyn for which it was hoped to obtain a Dutch barn.

The writer did not hear anything further about the Van Nostrand

barn and assumed that it was "safe." In September, Louis

Caputzal, a Dutch Barn Preservation Society Trustee who has family

connections on Long Island, went to look at the barn and found

that it was gone! The barn had been demolished about two weeks

previously. When the writer visited

the site, nothing was left. The ground surface on which the barn

had stood had been graded, obliterating every trace of its existence.

The writer found the elder Mr. Rottkamp at the site, cutting a

piece of grass along Hempstead Turnpike. Mr. Rottkamp said that

the barn had been broken into on numerous occasions and had been

used as a hangout by "crack" addicts. A demolition permit

was obtained from the Town of Hempstead, and the job was duly carried

out. The Rottkamps had indicated to Mr. Smits that they were interested

in the preservation of the barn, but did not inform Mr. Smits that

they had obtained a permit to destroy it! A sad loss, indeed.

The author, an architectural historian, serves

as historic restoration consultant to the Nassau County Museum.

Excerpts from Architectural

Analysis Report, Schenck-East of Sharon Barn

by John Stevens

Foundation. The ground frame of the building

was supported on a series of stone piers, spaced in accord with

the bents. As the ground sloped down from east to west, there was

a crawl space under the west side of the barn.

Sills. Sills were of oak, each in one length,

mortised and pinned at the corners. There were three inner sills,

two corresponding with the line of the main posts, and one in the

middle of the building. The two side inner sills were let into

the end sills with a half lap dovetail while the center sill had

a full lap dovetail. The side inner sills had a rabbet 3 inches

in width and 1 1/2 inches in depth on the inside edge to receive

the flooring. The center sill had two such rabbets. Transversely,

at each inner bent the three inner sills were supported on oak

sleepers that consisted of tree trunks flattened on two faces.

These in turn were supported on stone piers. Timbers were laid

on these, halfway between the side inner sills and the center sill

to bear under the flooring.

Floor. The center aisle (threshing floor) measured

23 feet in width. It had loose floor boards, 1 1/2 inch in thickness,

laid in the sill rabbets.

Framing. All exterior wall posts were of oak.

The purlin posts, anchor beams and plates were of pine. The side

wall posts were slightly more than 13 feet in height, and about

9 inches square. The purlin posts were slightly over 22 feet in

height. They measured about 9 inches transversely and 12 inches

on the face; slightly less in the end bents.

- The outside wall posts were connected with the purlin posts

by horizontal timbers set at 6 feet 9 inches above the threshing

floor on the west side and at 6 feet on the east side, a difference

not understood.

- The purlin posts were connected at a height of about 11 feet

above the floor by anchor beams. The three inner anchor beams

measured about 12 inches in width by 20 inches in depth. The

end anchor beams were 17 inches in depth. The tenons of the anchor

beams protruded about 12 inches beyond the outside faces of the

purlin posts through which they were mortised. They were each

slotted for two wedges that bore against the face of the posts.

In addition, they were pinned through the post. The ends of the

tenons were shaped in a rough semi-circle. The anchor beams were

also braced to the posts. Braces of the end bents measured 6

feet in length, exclusive of their tenons, while those of the

inner bents measured 4 feet on the west side and 4 feet 6 inches

on the east side, corresponding with the difference in the height

of the side wall ties on each side aisle.

- Additional transverse links were applied to the first, third

and fifth bents from near the top of the side wall posts to the

purlin posts and connecting the purl in posts near their tops.

The protruding tenons of these ties were wedged and shaped in

a rough semi-circle.

- The bents were connected by timbers at the same height as

the lower side wall ties, as well as by the plates. There was

an intermediate post between each bent in the side walls. The

plates were braced to all posts in a regular pattern. Braces

were also applied in the end walls between the horizontal ties

and the posts.

- The rafters were regularly spaced at each bent, with an intermediate

rafter between each of these. The foot of each rafter was made

with a cog that lay in a slot in the side plate and bore against

the tenon of the side wall post. The rafters were mortised and

pinned at the ridge and lay on the purlin without being fastened

to it.

Doors. There had been double wagon doors in each

end wall. They were outward opening and had been hung on wrought

iron strap hinges. The pintles for the north doors were in place.

A pair of doors, possibly original, survived in the north opening,

of three-batten construction with braces, nailed with rose-head

nails. The marks of strap hinges were without the characteristic

Dutch nailing pad. These doors had been secured with hooks and

eyes to a vertical pole that went into a mortise in the underside

of the anchor beam and into a corresponding socket on the floor.

In addition, there had been a door in the south wall at the extreme

east side, to admit animals to the stall area. There was also a

door in the west wall, towards the north end of the barn.

Martin Holes. On the north gable, where part

of the original siding survived, was one of probably three martin

holes. The main part of the opening was 7 inches wide. It had a

pointed top, above which was a small inverted triangle. These openings

were characteristic of Dutch barns of the Upper Hudson and Mohawk

valleys. The shape of the opening in this barn can be found in

a number of other examples.

Roof. The roof was boarded with waney-edged

boards, approximately 6 to 10 inches wide, laid with a space between

them. The shingles probably had an exposure of about 12 inches.

Pent Roof. On each end wall, over the main door

openings and extending about one  foot

six inches beyond them on each side, there had been a shed roof.

The projection of the roof could not be determined. Each of these

roofs had been supported by three horizontal struts, about 4 inches

square, made with tenons that went through mortises in the end

anchor beams. The tenons extended about 10 inches past the inside

face of the anchor beam. A vertical wedge through a mortise in

the tenon bore against the anchor beam to secure the strut. foot

six inches beyond them on each side, there had been a shed roof.

The projection of the roof could not be determined. Each of these

roofs had been supported by three horizontal struts, about 4 inches

square, made with tenons that went through mortises in the end

anchor beams. The tenons extended about 10 inches past the inside

face of the anchor beam. A vertical wedge through a mortise in

the tenon bore against the anchor beam to secure the strut.

Detail of an anchor beam tongue, Van Nostrand-Rottkamp

Barn, February 1991. ->

(Click above photo for more views of the Van Nostrand-Rottkamp

Barn.)

NEWSLETTER

Spring 1993, Vol., 6, Issue 1, Part Two

|