|

Dutch Barn Preservation Society Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation NEWSLETTER, SPRING 1995, Vol. 8, Issue 1 THREE HUNDRED YEARS: The Van Bergen-Vedder Barn A barn built for Marte Gerritsen Van Bergen circa 1680 stood on Vedder Road, near Leeds, Greene County, New York until a few years ago. The barn collapsed,and finally was bulldozed away. The following two articles, the architectural plans, and the photographs record both the special characteristics of this barn, and its place in the continuum of barn construction techniques. Barn construction transferring the aisled forms of Northern Europe to New Netherland began about 1626 when the first Dutch-style farms were established at Manhattan. In 1630, farms were established near Fort Orange on the upper Hudson. Some early barns in both of these locations were built on the aisled plan, and included housing for the farm family. These large combination buildings, common in the Netherlands and Scandinavia, proved impractical in the New World, and soon were replaced by farm compounds which included small houses for families, hay barracks, and separate barns for the storage and threshing of grains and for sheltering horses and cows. The separate barns retained the interior framing of the combination buildings. Inside were large beams, supported by columns which rose to the roof purlins. These beams hung over the center threshing floor. Flanking aisles to the right and left of the threshing floor housed livestock and often included a built-in manger and a grain bin. Barn construction in the aisled style stretched forward through time until the 1840's in areas of entrenched Dutch and German settlement. The Van Bergen- Vedder barn, which survived over 300 years, was an elegant example of the genre, now known as the Dutch barn. Earliest known photo of the Van Bergen Barn, 1928.

Dorothy Scanlon is seated on her horse Midgie. Marte Gerritsen and His Barn by Shirley W Dunn Marte Gerritsen Van Bergen was not Dutch. He came from Bergen, on the coast of Norway. As an outsider, he was typical of about half of the early immigrants to the Dutch colony of New Netherland. He arrived in 1630 to become a servant of Kiliaen Van Rensselaer in Rensselaerswyck, near present Albany. Van Bergen rose to prominence in Rensselaerswyck and Albany, established a family, and died after more than sixty years in America. A few farms had been established in the area of present Catskill in 1650, by the Director of Rensselaerswyck, who bought the area from the local Indians. Although the head of the Dutch West India Company, Peter Stuyvesant, refused to give Rensselaerswyck a patent for the land, the men who had leased farms from the Van Rensselaers in anticipation of the patent were allowed to remain on the farms in their own right. Thus settlement along the Catskill Creek by the Dutch was begun. In part because the land did not belong to Rensselaerswyck, and was free of payments to the Patroon, other purchases of Indian land by Dutch investors soon followed. In 1678, Marte Gerritsen Van Bergen and Sylvester Salisbury jointly bought five flats, including one called Potick, on the Catskill Creek at present Leeds, from Mahakniminaw, leader of the Catskill band of the Mohicans, and other Indians. Salisbury died, and the March, 1680 patent for the land was issued to Marte Van Bergen and to Salisbury's wife, Elizabeth. In 1688, a new patent, encompassing more land by expanding the boundary, (without buying more land from the Indians, who protested) was issued to the purchasers. Marte Van Bergen and the Salisbury interest represented by Elizabeth and her new husband, Cornelis Van Dyck, shared the extensive lands in their patent and shortly established at least two tenant farms. On one, the partners persuaded the tenants to erect buildings in lieu of rent. On the other, Marte Gerritse erected the structures, including a barn, to attract the tenant, who was his wife's brother. Marte Gerritse Van Bergen's barn was mentioned in both leases relating to these two farms: "March 7, 1681 ... Maerten Gerritz van Berghen acknowledges

that he has let to ... Gerrit Teuniz [Van Vechten] and Jonas Volckertsz

[Douw] his farm lying at Katskill [now Leeds] in the Maize land

(named Quaiack), comprising the just half of the foremost piece,

with house, barn and orchard, as it is occupied by the lessor.

The lessor shall lease therewith eight horses, eight cows and four

heifers, a wagon, four extra wheels, a plow, a harrow with iron

teeth, and a winnowing fan; the lessees shall likewise possess

and have the disposition of all the lessor's claims to the half

of Pooteeck [Potick] as of the said farm for the time of the next

six years... for the first three years, twenty-two beavers yearly...

and for the last three years, twenty-five beavers yearly, together

with a hundred skipples of maize yearly for the aforesaid six years

... The lessor promises to build a rick [hay barrack] there this

present year and to have doors made for the barn . . . " Jonathan

Pearson, trans. and A.J.F.

"March 23, 1682 ... Mr. Cornel is van Dyk, husband and guardian of Elisabeth Beek, late widow of Capt. Silvester Salisbury, of the one side, and Andries Janse, eldest son of Jan Thomas [Witbeck] and Hendrik Janse, his brother... have hired... half of the arable land lying in Katskill, consisting of the two flats, the first where Gerrit Teunis [Van Vechten] lives and the second called Potick, and that for the time of ten successive years... the lessor shall deliver upon the said land four milch cows and four draught horses... As rental of the said land, the said Andries and Hendrik Janse, at the end of ten years, shall deliver a proper dwelling house of twenty-two and a half feet square, covered with shingles and having a stone cellar as large as the house, which house shall be delivered over, glass, roof, floor, and wall tight; likewise a barn of fifty-two and a half feet long and as wide as the barn which Marte Gerritse has built there, which they shall deliver over in substantial and good repair as to wall and roof... the lessees shall have half of the land at Potick ... for which they shall pay to the lessor fifty skipples of wheat or a hundred skipples of maize... but if the lessees do not desire to hold said land Potick any longer they shall be released from this obligation." Jonathan Pearson, trans. and A.J.F. Van Laer, ed., Early Records of the City and County of Albany and Colony of Rensselaerswyck, Vol. 2, (Albany: University of the State of New York, 1916), 153-155. A "foot" was slightly over eleven inches by today's measure, so the house and barn were not quite as large as the contract reads. From these leases, it is clear that the barn of Marte Gerritsen Van Bergen was built after March, 1680, when the Patent was given, and before March, 1681, when the barn was mentioned in the lease. Completion was apparently still in process in spring, 1681, as the doors had to be added. Considering his age and position, it is unlikely Van Bergen built the barn with his own hands. Where the timber was cut, and who did the work, were unfortunately not specified. While some barn contracts exist, there seems to be none on file for this barn. The barn of Marte Gerritsen is believed to be the same barn which, somewhat altered, survived through much of the twentieth century in Leeds. In 1884, when a history of Greene County was being prepared, historian Henry Brace wrote about the barn. Brace had access, not only to early documents, but to the traditions of the family and the locality. He wrote in the History, "The first building at Old Catskill [Leeds], and the first within the patent, was erected by Marte Gerritse Van Bergen, about the year 1680. It was a barn of considerable size, being more than fifty feet square, and stood near the spot where Henry Vedder's barn now stands. It may have been on the very spot, for it appears to be a well founded tradition that portions of the oaken frame of the first barn are also portions of the second. The records make no mention of a house in the neighborhood at this time, but the probability is that one was built at the same time with the barn. "Marte Gerritse Van Bergen, the patentee, never lived at Old Catskill. His elder sons, Gerrit and Martin, were brought up on their father's estate near Fort Albany, and made their home here only after they had become men. In 1721 they, their brother Petrus, and Francis Salisbury and his son Sylvester, divided a portion of the patent among themselves. Petrus then sold his portion to his brothers," History of Greene County, New York with Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men, (New York, J.B. Beers & Co., 1884), 96. The frame remaining within the barn in the twentieth century had rare curved soffits on the braces, large columns, and massive anchor beams. There is every reason to accept the tradition that much of the barn survived from 1680. Also, it is clear from Brace's account that the alterations to the roof which are detailed in the drawings and text accompanying this article, and other changes, were made before 1884. Note that Brace had apparently not read the lease quoted above, which mentions that a house, as well as the barn, had been built. By tradition, this small house of stone was opposite the barn, and later, in 1729, became a wing (now gone) of a brick house built by one of Van Bergen's sons. In 1721, when Van Bergen's three sons made a division of the farm at Leeds on present Vedder Road, and of the Potick flat to the northwest held in common with the Salisbury heirs, the deed of partition mentioned Gerrit Van Bergen's dwelling house, suggesting that Gerrit, the elder son, was living on the property, perhaps in the old house. Gerrit and Martin in 1726 traded land at Coxsackie with a third son, Petrus. According to tradition, about 1729 the two built themselves substantial houses on the 1680 farm established by their father. One of these two houses was pictured on the well-known Van Bergen Overmantel. The Overmantel, a painting on boards, survived when, in the 1860s, the old stone house was torn down and a new Victorian house, (still standing), was erected on the site. The Dutch barn shown in the Overmantel painting was not the 1680 Van Bergen barn mentioned in the leases. The second house, which was built of brick, still stands today, a half mile to the west of the stone house shown on the Overmantel. The brick house stood opposite the 1680 Van Bergen Dutch barn, and, according to tradition, incorporated the original stone house as a kitchen wing. This part of the Van Bergen farm, containing the brick house and the Van Bergen barn, in 1 774 became the property of Arent Vedder, of Schoharie. The house and some acreage have remained in the hands of Vedder family descendants to the present day. Marte Gerritsen Van Bergen came to New Netherland in 1630. He was probably close to twenty at the time. How was it that he had young sons, who, in 1729, were just getting established? What appears to be a generation gap relating to the Van Bergen barn and the Overmantel painting can be explained by his late second marriage. Marte Gerritsen and Jannetje Teunis Van Vechten, his wife, had no sons before she died, leaving him a widower. On January 21, 1686, Marte Gerritse Van Bergen, by then an old man in his seventies, took as his second wife Neeltie Myndertse, young daughter of Myndert Fredericks (Van Iveran). In the ten years before he died, Neeltie and Marte Gerritse had five sons, two of whom died, one as an infant, and one as a young man. The survivors were Gerrit, born in 1687, Marten, born in 1692, and Petrus, born in 1694. This later family was far removed in time from Marte Van Bergen's early years in New Netherland. Marte Gerritse died in May, 1696, leaving a large estate including his share of the land at Catskill, two parcels at Coxsackie, a sawmill on Marte Gerritsen's kill at Coxsackie, pastureland on the Bevers Kill on the outskirts of Albany, the house and lot in the City of Albany, and his farm, lying opposite the south end of Castle Island, where his widow, Neeltje, lived. Van Bergen's will directed that when his sons came of age or married, they were to have the land at Catskill. Once the division of the Leeds property had been made, sons Marten and Gerrit did settle down at Leeds in sight of Marte Gerritse's barn. They used and preserved it until the property went out of the family's hands in 1774. A Last Look at the Van Bergen- Vedder Barn

by John Stevens The Van Bergen-Vedder barn was a most impressive structure. Apart from the massive size of the anchor beams, I was impressed with the curved-soffit anchor beam braces which were similar to specimens in the Jan Martense Schenck house, c. 1677, in the Brooklyn Museum, the Luykas Van Alen house, 1737, at Kinderhook, and the Leandert Bronck house, 1738, at Coxsackie. Braces of this form seemed to be characteristic of Dutch-American timber-framing practice, at least as far as it applied to houses in the earlier period. In the Old World Dutch context, anchor beam braces which were occasionally curved were more often shaped with an elaborate profile. The presence of curved-soffit braces in the Van Bergen-Vedder barn with their affinity to the Jan Martense Schenck house seems to be a confirmation of the barn's early date. A feature of the Van Bergen-Vedder barn that was unlike any other Dutch-American barn was the series of trusses erected on each of the six "H" bents that carried purl ins on which the rafters were supported (see centerfold drawing). The column purlin plates were redundant, and yet had been used at one time to support the rafters because they were chamfered at the locations where the rafters had lain against them. The rafters, themselves, had redundant notches, some with broken pins in them that indicated they had originally been supported by the now disused purlin plates. The craftsmanship of the trusses was of a high order and comparable to the "H" bents. The timber used in them appeared to be the same (a species of pine) and the patina the same. The purl ins carried on the trusses were slightly smaller in section than the "H" bent purlin plates and the wind braces of the trusses appeared to be marginally lighter than those of the "H" bents. The pattern of the two sets of wind braces was not the same, there being a greater number of braces in the "H" column set. Interior of the Van Bergen Barn, 1969. Note sidewall girt and post system. Photo by John Stevens. The barn seemingly had a major rebuild in the early nineteenth century when the present side wall height and roof pitch were achieved. John Fitchen was of the opinion that the trusses and the purl ins on them that carried the rafters were part of the rebuilding. And yet there was something about these trusses - their form, quality of workmanship and patination - that made it seem just possible that they might have been part of the original construction. The writer somewhat reluctantly decided against this possibility because it seemed that it would not work out to have the rafters in contact with both purl ins on each side because it would make the roof pitch excessively steep, and the side aisles abnormally narrow. Also, if the existing rafters were the original ones and had been in contact with both the "H" bent purl in plates and the truss purl ins, one would have expected that they would have shown two redundant notches, but I could not see evidence of double notches on each rafter. The form of the trusses was much the same as similar trusses the writer had seen and measured in the Clark-De Wint house, built in 1700 in Tappan, Rockland County, and in the c. 1700 Van Hoesen house at Greenport, near Hudson, Columbia County. Both of these houses have walls of masonry construction. Evidence of the former existence of such trusses survives in the c. 1722 Ariantje Coeymans house, and William McMillen of Richmondtown Restoration on Staten Island found evidence of roof trusses in a fire-damaged early eighteenth century stone house on Staten Island. While roof truss systems are rare in Dutch-American usage, they were the normal, characteristic practice in the Old World in buildings of all types as can be seen in the sectional drawings that illustrate Het Nederlandse Woonhuis by Meischke and Zantkuijl, published in 1969. A difference that exists between the trusses in the Van Bergen-Vedder barn and the ones in the Clark-De Wint and Van Hoesen houses is that in the barn the tie-beam is mortised into the canted struts, and in the two houses the canted struts mortise into the undersides of the tie beams. This latter condition is the one that prevails in Old World examples. Another difference between Van Bergen-Vedder and Old World usage is that in the latter the canted struts stand directly on the beams, while in the former they stand on longitudinal timbers that are let into the anchor beams. These footing timbers, like the purlins, are in one piece the whole length of the barn. On my first visit to the barn, I sketched a cross-section of it and made notes, but did not take any measurements, in part because a ladder was not available to measure the height of the columns and the trusses. I did take a number of photographs. In 1970, my wife and I made a month's visit to Belgium and the Netherlands to look at old buildings that had structural and decorative characteristics that related them to New World examples. My contact in the Netherlands was Henk Zantkuijl of the Amsterdam Bureau Monumentenzorg (Conservation of Monuments) who had an extensive knowledge of Netherlands timber-framed buildings. One day, Friday, April 10, Mr. Zantkuijl and his assistant took me to the Openlucht museum (Open Air Museum) at Arnhem. It happened that on the way (I did not make a note of the village it was near) we passed a large, weatherboarded barn with its gable end close to the road. Its end wall siding had been removed for some reason, fully exposing the construction. It had a roof truss system almost identical with the Van Bergen-Vedder barn, and its rafters were supported on the upper and lower purl ins. The driver was anxious to get on to Arnhem, and I had the briefest look at this barn and did not have the opportunity to take photographs of it! An opportunity missed that I have regretted ever since. The parallel of the Van Bergen-Vedder barn with this Old World barn stayed with me, and in 1972 I went back to the Van Bergen-Vedder barn equipped with a two-piece aluminum ladder so that I could properly measure the upper part of an "H" bent and a truss, and plot on paper if it was possible that the trusses were integral with the original condition of the barn. If I could lay down accurately the relative positions of the purlins, the pitch of the rafters could be plotted in contact with both purl ins and it could be demonstrated if the trusses were, or were not, part of the original construction. This I did on May 28, also on this occasion taking more interior photographs. I missed taking some important measurements. I did not determine if the longitudinal head-height struts and transverse struts were the same height on both sides of the threshing floor. I concentrated my measuring on the north side of it. At the time, I was not as conscious of the customary difference in the height of the longitudinals as I became later on. Also, I was not able to determine the threshing floor structural system. The original floor planks seemed to be in place, each in one piece, about 28 feet long and lying in rabbets in the column sills. At the west end of the building, because the ground sloped in that direction, it was possible to see the underside of the floor planks, which were rough hewn. Interior of the Van Bergen Barn, 1969, showing granary room. Photo by John Stevens. When I saw the barn in 1972, its condition had deteriorated. The last time I saw it, on June 21, 1975, the roof had collapsed along with the west gable, but the east gable, on the roadway, still stood. After the barn at Phillipsburg Manor was destroyed by fire, and while the major part of the Van Bergen-Vedder barn was still in reasonably sound condition, I recommended to John Harbour, Sr., the Director of Sleepy Hollow Restorations (now Historic Hudson Valley) in a letter dated April 15, 1976, that it be salvaged and restored to its original configuration to replace the burned barn. Unfortunately nothing was done to save this exceptionally early building. Conclusions The c.1680 construction date for the barn seems to be firm. The principal points of conjecture are the original form of the roof and the width of the side aisles. The late Vincent Schaefer was of the opinion that the trusses were an original feature, and that the rafters had originally been supported on the column purlin plates and the truss purl ins. However, he had not measured the bents and trusses and could not be sure how the slope of the rafters in this arrangement (if not in itself excessively steep) would affect the width of the side aisles. The. writer's measurements, as laid down on the drawing, seemed to show that the use of lower and upper purlins to support the rafters did indeed produce too steep a roof, and too narrow side aisles. And yet there is precedent in Old World Dutch barns for truss systems carrying upper purlins. The early date of the Van Bergen-Vedder barns made it seem all the more probable that it might have followed Old World precedent. On the drawing, the large scale section shows the building as found; the smaller scale section shows, on the left, a reconstruction of the original roof pitch retaining the present aisle width. On the right side the roof is shown as proposed by Mr. Schaefer. This arrangement results in a side aisle width of eight feet. With the resulting steepness of roof, and elongation of the rafters, there would likely have been collar ties. Collar ties would probably have been a feature of the roof without the trusses. Regrettably, the rafters were not examined for the presence of lapdovetail notches for collar ties. Close-up of lower hinge on small door beside wagon doors of the Van Burgen barn. Photo by Vincent J. Schaefer. While the writer's suspicion is that the trusses were in fact part of the rebuilding that the barn underwent in the early nineteenth century, one ponders the fact that the form of the trusses so closely follows Old World precedent, and how the carpenter who framed them, if, in fact, they dated to the early nineteenth century, could have designed them so true to form. The only places where trusses of this type existed, in the two New World Dutch houses that have been cited, would not likely have been known to him. It is just barely possible that in the early 1800s there still existed in the Hudson Valley a few barns from the seventeenth century that had trusses and a double purlin system that inspired the man who altered the roof of the Van Bergen-Vedder barn using this rather complicated method. In the early nineteenth century, many Dutch American barns had their roofs altered by extending the columns in relatively simple ways. The Decker-Bienstock barn in Ulster County can be cited as an example. On the other hand, it is possible, as Vincent Schaefer believed, that the trusses were an original feature, if we can accept a side aisle that was a bit narrower than usual? Alas! it is regrettable that this rare barn, and Mr. Schaefer's Teller-Schermerhorn barn with its steep roof, were not more exhaustively studied, or, better still, allowed to survive for our wonderment and enjoyment. Drawing of the Gerritse Van Bergen Barn, c. 1680. by John Stevens. ABOUT THE AUTHORS: JOHN STEVENS served for many years as historic preservation consultant to Old Beth Page Village, a living history farm and museum on Long Island. SHIRLEY DUNN was first president of the Dutch Barn Preservation Society and editor of the Newsletter for six years. Her book, The Mohicans and Their Land, was published in 1994. |

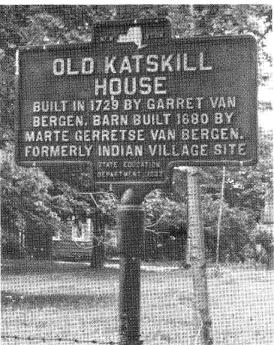

Historic

marker by Vedder house opposite Van Bergen Dutch barn. Photo

by Vincent J. Schaefer.

Historic

marker by Vedder house opposite Van Bergen Dutch barn. Photo

by Vincent J. Schaefer.