|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

SPRING 1997

Vol. 10, Issue 1An

Inventory of Dutch Barns in the Town of New Paltz in 1798

by

Neil Larson

A short time ago, I was invited to co-author a chapter for a book

on the architectural information contained in the assessment schedules

from the 1798 Direct Tax. Tom Ryan, a doctoral candidate from the

University of Delaware, where the project had developed, and I

were assigned to review and evaluate the lists that survived for

New York. The Direct Tax was the first levy made by the U.S. Government

on the states. It was instituted to raise money, approximately

two million dollars, to improve the nation's coastal defenses.

Unlike the income tax with which we are all- too-familiar today,

this tax was based on property value. To this end, every property

in the United States was inventoried and given a value. What a

remarkable record! Every house, farm building, mill, shop, every

building was itemized and described, in some cases, down to their

window size (it was this assessment that generated the myth of

the window tax) along with their lands and together with the slaves

that inhabited the property. This was truly a benchmark view of

the extent of cultural landscape in the United States at the end

of the eighteenth century.

Dutch

Barn on Libertyville Road in the Town of New Paltz possibly included

in the 1798 inventory. Photo by Neil Larson. Dutch

Barn on Libertyville Road in the Town of New Paltz possibly included

in the 1798 inventory. Photo by Neil Larson.

But, this story does not have a happy ending. As it turns out,

precious little of this information survives, especially in New

York. Because the Direct Tax was computed on aggregate property

values compiled by each state from summaries made by locally-appointed

assessors, state and federal records do not contain the actual

property-by-property inventories. These documents remained in the

hands of town assessors and have largely disappeared from view.

For New York, assessment lists for only eight towns have been located.

All but one are in the Hudson Valley: four lists survive from Ulster

County, two from Orange and one from Dutchess. Only one town has

a complete set of three assessment schedules: Schedule A, which

itemized houses valued at $100 or more (it is only this schedule

that survives in all cases); Schedule B, where houses valued at

less than $100 were recorded along with all other building types-including

barns-and improved land; and Schedule C, which was a census of

slaves residing in the town.

The town fortunate enough to have all three schedules is New Paltz

in Ulster County. There has been no secret to its existence. It

is a town document and a copy of it has been used for years by

local historians and Realtors at the Huguenot Historical Society

Library. However, to my knowledge, it was not until the current

project to recover and analyze the research value of the information

contained in the assessment lists that this extraordinary data

was looked at in a systematic way. Many interesting things were

discovered about the architecture of these towns and the region,

but you will have to wait for the upcoming publication of the book

to read about it. I am going to use the space here to reveal what

the assessments made in the Direct Tax have to tell us about Dutch

barns.

The immediate thing to recognize on the New Paltz B Schedule is

that it actually refers to certain barns as "Dutch barns." Since

plan dimensions are included in the entries (due to the fact that

the 88 barns so classified all have the square footprint on which

we now rely to distinguish Dutch barns), we can be confident that

historic and current usage refer to the same buildings. This early

occurrence is significant on at least two levels. First, it documents

the use of the term to the late eighteenth century. This is a wonderful

thing to see in print, to discover that the term goes back before

John Fitchen's The New World Dutch Barn or Helen Wilkinson Reynolds's

Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley before 1776, or any other

secondary source we have used as an authority. Second, this choice

of words indicates that the word "Dutch"

was a critical modifier two hundred years ago. It is unarguable

from this perspective that the term was actively used not only

to characterize a barn form, but to associate it to a cultural

group. There are names linked to all the barns on the list, and

this allows us to actually see who had

"Dutch" barns and who did not and determine the role

of ethnicity, kinship and class (for values are a key factor in

this assessment) in the choice of barn types. This process is helped

in that all barns were placed in some kind of descriptive and dimensional

category. Other barns listed in Schedule Bare classified as simply "barns," "frame

barns," "log barns," and there is one "crotch

barn."

With Dutch barns clearly identified in this way, we can have the

opportunity to interpret them in the architectural, geographical

and cultural contexts that the assessment lists create. For example,

the dimensional data for Dutch barns can be organized to document

the range of barn size and compare the scale of the building to

the relative wealth or the extent of arable land of farms. In New

Paltz, land is described and assessed on Schedule B and given a

geographical reference, so it would be possible to map farms and

estimate their productivity. (This still needs to be accomplished.)

We can immediately compare the ethnic, wealth and class distinctions

between Dutch barns and the others. Just a cursory review of names

confirms what is generally understood about Dutch barns: they were

owned overwhelmingly by the local "Dutch" families in

identifiably "Dutch"

communities.

It is important to realize here that "Dutch" in this

period was synonymous with "Not British," and in this

case Huguenots, Germans and Scandinavians were as "Dutch" as

the Dutch. The cultural division lines are clear and emphatic.

In New Paltz, British names are simply not linked to Dutch barns,

and "Dutch" is the dominant identity. (English barns

are just called "barns.") The localizing of ethnic identities

in the Hudson Valley can be seen by looking at the smattering of

assessments that exist elsewhere. Schedule B for the Town of Minisink

in the heart of the British cultural landscape of Orange County

does not list a single barn that is specified as a Dutch barn,

even though there are numerous dimensional similarities. (We cannot

rely on the absence of Dutch Barns in Minisink today as evidence,

because even in New Paltz, only one or two of the over 80 Dutch

barns inventoried in 1798 survive.)

There is another source of information in the New Paltz assessment

lists that involves the Dutch barn in another significant cultural

issue: evidence for the African-American presence on the eighteenth-century

cultural landscape. As noted above, a third schedule used for assessing

property value for the 1798 Direct Tax was a census of slaves.

Unlike the other two schedules, which gave names to the owners

and occupants of the inventoried properties, slaves were anonymously

enumerated by age and gender (the basis by which they were comparatively

valued). However, they were identified with their owners, so we

can identify who in New Paltz owned slaves and how many they owned

broken down by their age and gender. As with Dutch barns, this

data allows us to see the relationships of ethnicity, kinship and

wealth in slave-ownership more clearly. But, more importantly in

this instance, it allows us to examine the coincidence of slavery

and Dutch barns. By using the three assessment schedules together,

we are able to reconstruct the slaves' milieu and locate them in

the landscape of the town and on the farms where they lived. We

can see that they were employed in agriculture, commerce and trades.

Where were they housed? This remains a nagging question in slave

and architectural history, but the lists provide a certain insight

in the fact that they do not specifically link slaves to any dwelling

type while they list a variety of accessory buildings: kitchens,

ells, linters (leantos), outlets (outshots), shops and barns where

slaves would have worked and possibly resided. If nothing else,

it is significant to realize that over 83% of the 280 slaves that

were counted in the Town of New Paltz in 1798 lived on farms that

also had Dutch barns. Clearly the Dutch barn was a conspicuous

landmark in the African-American experience.

Using the data from the lists, let's now turn to some of the actual

information about Dutch barns and the cultural landscape in which

they existed.

Dutch barns and other barns

The floor plan of the smallest Dutch barn in the Town of New Paltz

in 1798 measured 30 feet by 19 feet, with the larger dimension

presumably being the facade. Two of these would practically fit

in the largest barn, which was listed as 60 by 50 feet. In between,

the barns ranged widely in size, although most (55) were from 45

to 50 feet wide. They were typically slightly rectangular; only

fifteen of the eighty-eight Dutch barns were exactly square in

plan. Ten Dutch barns measured 50 by 40 feet and eleven were 50

by 45. These were clearly the most frequently repeated dimensions

in the entire tax list.

The other barns cited on the list were significantly smaller.

The ninety-five barns entered simply as "barn" or "frame

barn" ranged from 22 to 48 feet along their principal facade.

These were what are commonly called English barns today, and would

have had their threshing floors and large wagon doors on an axis

perpendicular to the roof ridge. Still, they were frequently as

square in plan as the Dutch barns suggesting that by 1798 the Dutch

barn could have been evolving into the hybrid type seen in surviving

examples where the Dutch bent frame was preserved while the facade

and central aisle were rotated ninety degrees to the side elevation.

The median sizes recorded for "barns" and "frame

barns"

concentrate in the range of 30 to 45 feet, significantly smaller

than the median "Dutch" barns. The thirty additional

barns described as "log barns" were even smaller. The

smallest log barn measured only 16 by 15 feet. The median size

for log barns was at the higher end, however, although the largest

was only 30 by 20 feet. Therefore, in terms of scale, there was

a hierarchy of materials and form with the Dutch barn clearly the

largest and most substantial of all the barn types recorded in

the Town of New Paltz in 1798.

Dutch barns and their farms

When the data on assessment schedules A and B are combined and

organized by name of occupant, a fuller view of the farms in New

Paltz begins to emerge. This gold mine of comparative data has

yet to be examined in any detailed or systematic way, but even

in its relatively raw state we can identify the milieu of the Dutch

barn on a farm by-farm basis. Just in terms of buildings (the extent

of land and land value relative to Dutch barns still awaits even

cursory analysis), we can make some interesting observations concerning

common assumptions. For example, sixty five New Paltz farms had

both Dutch barns and stone houses. This combination represented

approximately three quarters of Dutch barns (73.9%) and stone houses

(75.6%). Thus, the image of stone house and Dutch barn together

is an accurate one. Still, twenty-three Dutch barns were paired

with wood houses, and at least two of those were log houses! More

than half of the Dutch barns (46) were the only other building

inventoried with the house. The other entries included a wide range

of outbuildings, such as hay houses, corn houses, smoke houses,

stables, and various shops and sheds. This indicates that for many

farms, even at the highest property values, the multipurpose Dutch

barn was the sole building directly linked to farm activity.

Dutch

Barn on Hurds Road in the Town of Lloyd. The Town of Lloyd was

part of the Town of New Paltz in 1798; therefore, this barn could

have been included in the 1798 inventory. Photo by Neil Larson. Dutch

Barn on Hurds Road in the Town of Lloyd. The Town of Lloyd was

part of the Town of New Paltz in 1798; therefore, this barn could

have been included in the 1798 inventory. Photo by Neil Larson.

After barns, the farm building most commonly listed is the "hay

house," which appears in 45 different entries. It is worth

mentioning in this context because it is paired with Dutch barns

in 31 of those instances (it is cited with other barns only five

times and without barns the rest). The dimensions of these hay

houses. range from 20 feet by 18 feet to 60 feet by 20 feet with

the median around 30 x 18 feet. These were not barracks. The measurements

describe a rectangular building of a standard width and of varying

lengths that would be similar to the adjunct frequently seen attached

to Dutch barns that are dedicated to hay storage, sometimes with

animal stalls on the ground or basement level. In 1798, the presence

of hay houses in this number and in combination with barns would

document the increasing importance of hay and, by extension, numbers

of cows (likely milk cows) in the farm economy. With only thirty

of them inventoried on the most successful farms, one supposes

that this is the harbinger of the Dutch barns' transition from

wheat to dairy facilities in this part of the region during the

early nineteenth century.

Dutch barns and class, wealth and ethnicity

Considering stone houses were the most highly assessed object

in the town, the correlation between them and Dutch barns firmly

associates the agricultural building with the wealthiest properties

in New Paltz. In fact, all the Dutch barns except four are associated

with houses valued $100 or above on Schedule A, stone or otherwise

(one of them belongs to the church and was not listed with a house).

In 1798, using just Schedule A, the average value of farms that

had stone houses on them was assessed 33% higher than the average

value of farms with frame houses ($2942 vs. $2205). If the most

highly valued farm in the town is removed from the list of farms

with frame houses (Cornelius Dubois's 1668acre property was valued

at $12,800), this value percentage of stone house farms over frame

house farms grows to fifty-eight percent. Much of this value difference

is represented in the houses themselves. Taken alone, stone houses

on Schedule A were valued, on the average, 216% higher than frame

houses on the same list ($429.19 vs. 198.85). Land values probably

playa role in this comparison, but the complex manipulation of

the 1798 assessment data has yet to be done. The class distinction

between stone houses and frame houses is further demonstrated when

properties itemized on Schedule B are considered. There are only

two stone houses on Schedule B while forty-four frame houses with

a value less than 100 dollars were tabulated there, ten more than

are recorded on Schedule A. Thus the frame house overlapped value

and class distinctions whereas the stone house did not. Log houses

were valued consistently below $30, some as low as one dollar,

and represented the lowest end of the socioeconomic scale in the

Town of New Paltz.

Dutch barns were not typical on leased farms. Of the 151 properties

listed as rented in the 1798 New Paltz assessments, Dutch barns

were identified with only fifteen of them. Among these, only one

was posted on Schedule B, the farms of lesser value. Of the remaining

fourteen found on Schedule A, six Dutch barns were on farms leased

to individuals who shared the same names with the owners. This

indicates that these farms were held within families (some owners

were identified as estates) and tenanted by kin. Eight Dutch barns,

less than 10% of the 88 inventoried in the town, were leased with

farms valued at over $500, some well over $1000, and one assessed

at $3500. So, Dutch barns were not characteristic of the leaseholds

of the lower socioeconomic classes.

Another way to associate Dutch barns in a class structure is

through their overt identification with the ethnic patriarchy of

New Paltz. The Huguenot Duzine and its kin were the dominant economic,

social and political class in New Paltz.The 1798 assessment lists

document the extent of this control and position the Dutch barn

as a landmark in this cultural landscape. Scanning the owners'

names for New Paltz's 88 Dutch barns, Huguenot names are quite

prominent, though not exclusive. Families with the names of Deyo

(12 Dutch barns), Dubois (10), Eltinge (3), Freer (12), Hasbrouck

(10), and Lefever (11) claimed two-thirds of the Dutch barns in

the town. The remaining thirty were distributed among twenty-two

names, only three of which had more than one but less than five.

Many shared names with a broader Ulster County "Dutch" genealogy,

like Dewitt, Jansen, Louw, Vanvliet and Vandermark. Others were

clearly German: Ein, Hardenburgh, Swart, Terwilliger and Wirtz.

Then, some were British in origin, like Broadhead, Birdsall, Donaldson,

Merrit, Wood and Waldron. The social and kin relationships of these

non- "Dutch" persons warrant greater exploration.

Dutch barns and slaves

Among the 280 slaves in New Paltz, 145 were male and 135 were

female. Eighty-four males (57.9%) were between the ages of twelve

and fifty and subject to taxation; sixty-seven females (49.6%)

were placed in the same category. Only one female was exempted

from taxation because of disability. These slaves were divided

among ninety owners. Exactly one-third of these owners (30)' possessed

only one slave. This group was evenly divided among three value

categories: taxable females (11), taxable males (10), and those

too young or old to tax (9). Fourteen of those listed owned two

slaves, and fifteen owned three. The numbers of owners decreased

steadily as the number of slaves per owner increased. The highest

number of slaves recorded for one owner was thirteen (seven males

and six females), five of which were taxable, although only ten

slave holders owned more than six slaves. Overall the ninety slave

owners represented a relatively small proportion of the census.

They constitute twenty-two percent of the 406 different names identified

as "occupants" for the 1798 Direct Tax. It can be inferred

from these statistics that slave owners were, to a very large extent,

land owners and were, other than in rare instances, in the wealthiest

class established in the assessments.

Looking at information about barns and other property provides

another way to address the African-American presence. Like the

stone house, according to the assessment lists, slave owners were

prone to have Dutch barns more than twice as often than English

and log barns put together. Slaves were also owned by people who

had shops (numerous blacksmithies and one each for weaving, carpet

and hat shops), mills (grist, saw, fulling) and a dye house. In

both cases, agricultural and industrial, the resource of slave

labor was a valuable commodity. Only seven slave owners had no

entries for agricultural or industrial buildings in the assessment.

Some were widows or estates; all likely had an association with

another unidentified person or work location.

Clearly, slaves were a commodity available only to a wealthy,

elite class. The emerging image of the slave's milieu in New Paltz

is one of a large, prosperous farm-often a network of farms and

shared labor linked by kinship-with a substantial, multipurpose

dwelling reflecting the status and diversity of the household and

a well-developed complex of agricultural support buildings. The

Dutch barn was a frequent component of this environment. And, consistent

with the cultural associations of the Dutch barn, a significant

proportion of slave-owners (72%) had surnames which immediately

identified them with New Paltz's leading Huguenot families.

The New Paltz assessment schedules for the 1798 Direct Tax are

priceless documents for exploring the geographical and cultural

milieus of the Dutch barn, simply because the assessors there made

the distinction in their inventories. It may be that this distinction

was made in no other place (assessment schedules did not follow

uniform standards, state to-state or town-to-town), but nonetheless,

there is a wealth of data with which to work, even if a single

barn no longer exists! This article only touches on what is most

obvious in and easily retrievable from the data. I have tried to

suggest some of the more compelling directions to go with the list.

Future work with the schedules, whether it pertains to Dutch barns

or other aspects of the cultural landscape, awaits completing the

difficult task of mapping the data. I hope in the next year or

so, the Hudson Valley Study Center will be able to organize some

courses and workshops to work with this document and, using computer

data base and mapping tools, recreate the landscape that existed

in 1798. This will greatly expand our understanding of architecture,

landscape and culture and allow us to visualize what people actually

saw two hundred years ago.

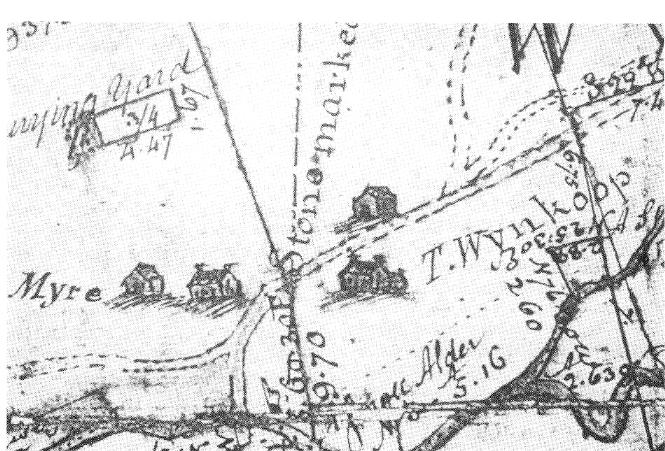

A 1796 map shows several farms with Dutch barns

along Route 32 near Route 23A in Greene County, NY. (Detail shown.)

Although this survey is not from New Paltz in Ulster County,

it clearly illustrates the former density of Dutch barns in areas

settled by Dutch or Palatine families. Photo by Shirley Dunn.

Source: Vedder Library, Greene County Historical Society, Coxsackie,

NY.

Neil Larson is Executive Director of the Hudson

Valley Study Center; State University of New York at New Paltz.

|