|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER,

SPRING 1999, Vol. 12, Issue 1

The Restoration

and Reconstruction of the John J. Post Aisled Dutch Barn, 1997-1998

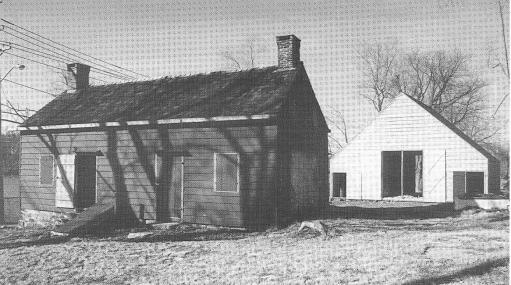

The John J. Post Dutch barn reassembled on the

Paul/Schueler Home site. The Paul/Schueler House (in foreground)

had previously been restored by the author. The right half of

the house dates to the late eighteenth century while the left

half dates to between 1820 and 1851. The house and barn are owned

by the Town of Clarkson, Rockland County, New York. All photos

by George Turrell.

By George B. Turrell

One day in the first decade of the nineteenth century, John J.

Post, a farmer in Rockland County, New York, commenced construction

of a small aisled barn in the Dutch style. Mr. Post's holdings

consisted of approximately 30 acres inherited from his father,

land which lay within the original South Moiety (half) of the

Kakiat patent. (1). A small but well located and drained piece

of land, it gently rises to the West, with Pascack brook and

Pascack Road running from north to south along the eastern border.

The great farms, houses and barns of the Hoppers and Van Ordens

were up the road about a mile to the North, in Scotland or Scotland

Hill as that place was known. John's small parcel was abutted

by his father's and brother's land, and it is reasonable to suggest

that pasturage was shared along the brook. So a small barn was

built, sufficient to the needs of the Post family, and remained

in their possession until 1893. The land and buildings passed

through a few more owners, until 1958 when the house, barn and

land, then consisting of only 3.8 acres, was sold to John and

Eleanor Sterbenz. (2) The records indicate that, for this farm,

agriculture had been a steadily diminishing livelihood, although

the surrounding land was not developed until the late 20th century.

The barn was thus not subjected to the pressure of business agriculture

that turned the ridges into pastures and swelled the neighboring

barns for more hay storage, stabling and garaging. By continually

serving its original function, a small barn for a small farm,

John J. Post's became the last aisled Dutch barn in Rockland

County, where at one time there were dozens.

More than one hundred and seventy-five years later, and after

the onslaught of suburban development engendered by Rockland's

proximity to New York City, Post's barn was documented by local

historians, notably Claire Tholl and Greg Huber. It squatted, gable

ends to the North and South, eight feet from Pascack Road, even

today narrow and tree shadowed, paralleling the banks of the Pascack

brook. Painted "barn" red, with mottled white roll roofing,

it dipped, swayed, bulged and otherwise indicated an antique building

succumbing to insects, rot, and gravity. The roof was tight though,

replaced in the sixties by John Sterbenz who had also replaced

most of the rafters and the west purlin plate. He sheathed the

roof with tongue and groove hard pine, and generally repaired the

building well enough to keep it functioning as a garage/workshop

for another thirty years. Greg Huber's documentation of the barn

during the early 1990s led to an offer from Mr. Sterbenz' son,

John Jr., for Greg to take the barn to his land in the Schoharie

Valley. Mr. Huber, deferring a dream, decided, instead, along with

John Sterbenz Jr., to donate the building to someone who would

keep it in the county. The barn would have to be moved, of course,

and the dismantling and restoration paid for. Interested parties

appeared, but were either dismayed by the barn's condition or disappointed

in its diminutive size. The approach of Rockland's bicentennial

and the successful restoration of the Paul/Schueler homestead,

(a property owned by the town of Clarkstown, Rockland County) led

to an interest in the barn by Charles Holbrook, town supervisor,

who championed the barn's move to the Paul/Schueler site. At Mr.

Holbrook's urging the town council voted to fund the Post barn

dismantling and restoration.

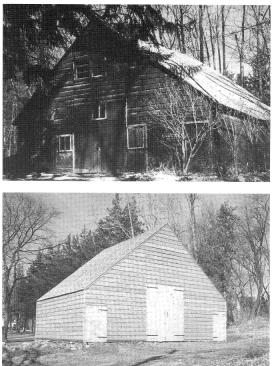

Top: John J. Post Dutch barn on original site prior

to restoration. Above: Restored J. J. Post barn on the Paul/Schueler

site.

The dismantling of the barn began on a humid 95 degree day, more

like late July than early June. For two days workers purged the

barn of engine blocks, car bumpers, fenders and seats, boxes, crates

and barrels, which had been the accumulated cargo of fifty years.

We eventually filled four forty- yard containers. The barn was

at last empty and we could examine what was left. The remnant floor

was first taken up to reveal that the main sills and joists were

of archeological interest only, being but wood mold in the soil.

The main posts were rotted and insect infested up three feet or

more. And so we began a woeful inventory: the side wall sills were

85% gone; four interior columns were shot out top and bottom; the

west purl in plate gone; the east purlin plate three fifths gone,

nothing reusable. All the rafters, excepting the gable end rafters,

were either rotted or replaced with 2 x 6 boards; the side wall

plates were rotted beyond use, as were the struts and girts; longitudinal

struts were missing; the side wall posts decayed beyond reuse;

the anchor beams all required repair, the north beam's weather

side was virtually gone to rot; six of eight anchor beam braces,

however were intact or repairable; the siding and roofing were

not reusable due to late 20th century replacement or decay; of

the sway braces, only four of the original twelve left. In short,

and what is easier to relate, we had left: four usable columns,

three anchor beams, six anchor beam braces, four sway braces and

two open dovetail braces from the side wall corner posts.

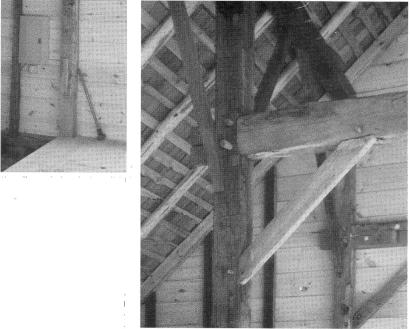

Close-up

of column showing scarf joint repair. Close-up

of column showing scarf joint repair.

Right: View of the anchorbeam to column joint.

Notice the square shape of the anchorbeam tongue and lack of

wedges. The distance from the top of the anchorbeam to the top

of the purlin plate is short resulting in the sway braces entering

the column below the anchorbeam.

I must report that our initial professional complacency began

to wear thin as we catalogued the damage, and wrestled with the

slimy, greasy, moldy and otherwise unmentionably encrusted bones

of this poor barn, all of us drenched in sweat and working 16 hour

days. The building nearly collapsed on several occasions. It was

at one point possible for a person (a 10 year old girl in this

case) to topple the entire bent structure by pressing lightly,

in a northwesterly direction on post 1 east, the South bent. It

was requested that she not do this. While disassembling the roof

with an all terrain forklift, the machine plunged into a soft spot

where the threshing floor had been, and the "up" lever

for the lift rack was inadvertently hit, sending the top of the

lift carriage through the hard pine roof. The lift became lodged

above the roof and could not be retracted without collapsing the

structure directly upon the machine and its operator. I cried.

We then completely rebraced the building with 2x10 boards, and

tying a string to the "down"

lever, I slipped into the safety of the woods. By pulling on the

string, the carriage came down, pulling a hefty chunk of roof,

but causing no damage. This was Thursday, midday, about 64 man-hours

into the process. Friday morning began the final assault. The temperature

was 97 degrees at 10 a.m. Humidity at 92% headed for 100% as thunderheads

rolled in from the Northwest. Like the cannonade at Gettysburg,

we could hear the rumbling hours ahead and miles away. By late

afternoon, the crippled main frame was all that was standing, as

we raced to dismantle before the rain could soak our timbers. Premonitory

winds blew the chaff and detritus all over our sweaty selves, a

reminder of the threat. At 7 p.m. as the trees thrashed and sparse

robin's egg sized raindrops struck us, the last bent came down:

trunnels removed, the braces withdrawn, the columns were separated

from beams with the mighty white oak beetle; they were lifted,

stacked and covered. The rain came, and the wind lashed, the thunder

crashed and the lightning flashed, the water washed us and we were

happy and tired and gratefully stupefied. We trucked what was left,

along with the ruined pieces that held information (of mortices,

braces, material and method of hewing and so forth) about twelve

miles away to an empty modern barn with a concrete floor. We stacked,

stickered and left, to return 11 months later.

Once again, like the bones of the Romanovs, the material was

reloaded and carried twenty-five miles south to our facility in

Closter, New Jersey, where the restoration of the frame would be

undertaken. At this juncture, it would be unreasonable not to ask

what the purpose of all this might be, particularly considering

that the restored building would be essentially a replica, and

a replica of an undistinguished farm building at that. When one

further considers that this project was being underwritten completely

by the town of Clarkstown, New York, with public monies, duly approved

and voted on in an election year, an extraordinary kind of commitment

becomes evident.

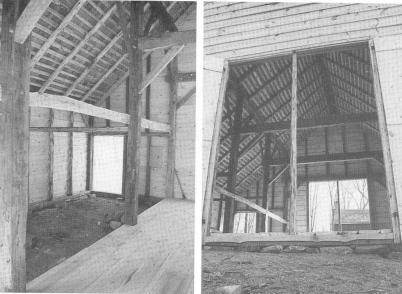

Left:

View of the left side aisle Left:

View of the left side aisle

Right: View of the interior from the wagon door.

Only a year before, Clarkstown had also funded the complete restoration

of the derelict Paul/Schueler house, (circa 1790-1810) a timber

framed farmhouse on the town's parkland that my firm had been contracted

to document and then restore. Under thousands of pounds of debris,

garbage (including 86 toaster ovens, but that's another story)

and later additions, was a two room farmhouse with a jambless fireplace,

enclosed garret ladder,original hardware and finishes and a little

federal parlor. It was to the immediate north of this farmhouse,

that its contemporary, the Post barn, would be raised. All the

main buildings of a typical small Dutch-American farm of Rockland

would be in place and in their proper relation. I must express

wonder at and gratitude for the foresight and imagination of Clarkstown

government, Charlie Holbrook, town supervisor, and Chuck Connington,

parks director, especially.

Our contractual responsibility, ambition and aesthetic was to

restore the barn so that John post, should he visit, would not

be able to tell that it was 1998, by materials technique or hardware.

And so in late April 1998, Paul Hofle, B.J. Allen, Jeremiah Dickey

and I began to locate and gather materials for the restoration

process. Dressed fieldstone was collected from a farmhouse being

demolished for a gigantic Pet Spa, (to the amusement of the developer)

and great sandstone flats were pulled from an abandoned quarry.

Twenty-four straight trees, 26 feet in length were felled in Ulster

County for rafters by Herb Lytle. We needed 2000 board feet of

white pine planks, vertically sawn, thirty-five squares of split

cedar shakes, 60 pounds of cut nails, 16 strap hinges. 900 board

feet of sawn white oak and two hundred linear feet of new old-stock

chestnut and white oak (salvaged from other area barns or purchased

upstate) were prepared and pressure treated joists were shipped

from northern Virginia. A thousand of feet of random free-edge

shake purlins were cut and peeled, black locust logs were squared

and split out for three hundred thirty-four trunnels to be drawn

on the trunnel bench. Ten tulip poplar trees felled and sawn for

the 1080 board feet of 2"x16" planks for the threshing

floor.

NEWSLETTER,

SPRING 1999, Vol. 12, Issue 1, part two

|