HVVA

NEWSLETTER, January 2006

(Click

on graphics/photos for larger view)

HVVA Newsletters

EVIDENCE OF CROSS-WINDOWS IN DUTCH-AMERICAN HOUSES:

The cross-window (kruizkozijn) was the standard window form used

in northern Europe in the better class of house. The particular

form of it used by the Dutch, came to North America with them in

the early 17th century. Typically, the upper two (of four) openings

in the frame were glazed flush with the outside of the frame. The

top edges of the leaded glass panels were housed in a groove cut

into the underside of the head of the frame. The glass panels were

stiffened at each horizontal division in the glazing by means of

iron rods (guard bars) attached to the lead cames by wires soldered

to the cames and twisted together around the iron rods. The ends

of the iron rods were flattened, and attached to the frame with

small nails. Sometimes, hinged casements, glazed in the same way

as the upper openings, were fitted on the inside to the lower openings.

The lower openings also had external hinged shutters.

A relatively small number of examples of this type of window are

know to survive. The following are known to the writer, and it can

be hoped that evidence of others may yet be found.

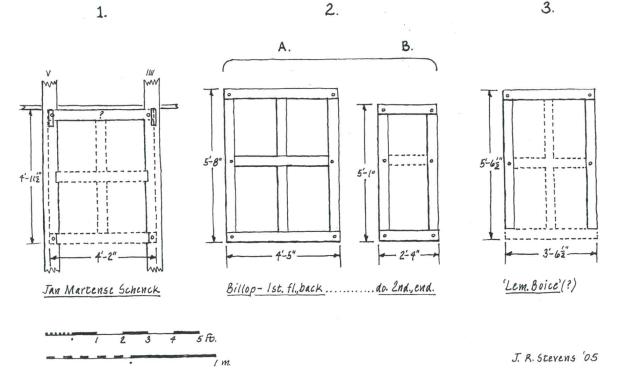

1. Jan Mark-use Schenck house, c. 1670? This timber-framed

house formerly stood in the Flatland section of Brooklyn, next to

a watermill. It was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1952 and was

dismantled in that year by the E. W. Howell Company (which also,

later, did much of the restoration at Old Bethpage Village Restoration).

The parts of the Schenck house were stored under a highway until

1962 when funds became available to reconstruct the house inside

the museum. Unfortunately, a leak from the roadway degraded some

of the timbers of the house, and in particular the wall posts III,

IHI, V (west wall toward the south end) that had formed the sides

of a transomed doorway and a cross-window. The head of the window

survives (or is it possibly the transom?). The head, transom and

sill were morticed into the wall posts IIII and V that formed the

jambs of the window. The transom of the doorway also survives. Degradation

from water damage to these elements is indicated in the field notes

prepared by Ian Smith for the Brooklyn Museum. The restoration of

the house was largely in the hands of the late Daniel M. C. Hopping

with some input from Henk J. Zantkuyl. (See Dutch Vernacular

Architecture in North America, 1640-1830 [hereafter

D.V.A./N.A.] PI. 17, 41)

2A. Christopher Billop (Conference) house, c. 1680?

This stone house stands at the southern tip of Staten Island. It

survives as an anomaly in the area of Dutch settlement in being two

stories in height, with a center hall. Because it was built for an

Englishman, there are some Ang-licizations, such as the use of plain

tiles on the roof, (instead of pantiles) and possibly, outward-opening

casements on the windows as will be discussed. The only other early

'mansion' comparable with the Billop house is the Ariaantje

Coeymans house which is about 35 years 'newer'. The Billop house

had cross-windows on both its floors. Those on the second floor were

slightly shorter than the ones on the first floor, however the bottom

openings were the same size in all windows. The facade (west wall)

windows were replaced in the 18th century with double-hung sash windows

that were taller, and somewhat narrower than the original ones. Maybe

about the same time as the front windows were altered, a lean-to

was built across the back of the house (east side) encapsulating

four cross-windows within it, in mostly near-original condition.

These window frames were exposed in the recent past when work was

being done within the lean-to, at which time they were measured and

photographed by William McMillen. Subsequently they were covered

over again. The top openings had been glazed in the Dutch manner,

flush with the outside of the frames, but exceptionally the glazed

panels were stiffened internally with wooden rods set in holes in

the jambs that did not correspond with the horizontal divisions of

the glazing ('saddle bars' in English usage). The inside edges of

the frames are molded, precluding the use of inward-opening casements.

These lower openings could have had external shutters in the Dutch

style- or possibly outward-opening casements as was usual in a British

context? (See D.V.A./N.A., PL 2, 3C)

2B. On the second floor of the house at the south

end, west side there survives in place a half-cross-window (kloosterkozijn)

from which the transom has been removed and double-hung sash inserted,

(see D.V.A./N.A., PL 76E, reconstruction by William McMillen)

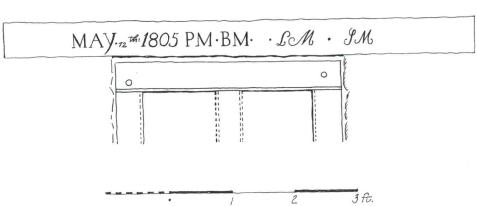

3. House identified as 'Lem. Boice'. One-and-a-half

story stone house, earliest section (north end) built in the early

18th century, with a stone and a timber-framed addition, both from

the 18th century. It is located north-west of Kingston, near route

209. A cross-window frame survives in the front (east) wall of the

original part of the house. The transom and mullion were removed

to accommodate double-hung sash. Window sill replaced. The head projects

past the jambs about one inch with a groove in its underside to house

the top lights of leaded glass. The interior details cannot be inspected

because they are covered by later trim. The lintel stone over this

window has a well-cut inscription (initials) and the date 1805. This

house requires further investigation, among other things to determine

the significance of the 1805 date on a building that is obviously

much older than this? This house and its cross-window wasered'

in December, 2005.

Ariaantje Coeymans house, c. 1716. Two-and-a-half

story stone mansion at the north end of the Village of Coeymans,

on the Hudson River south of Albany. It has two rooms on each floor

separated by central hallways in which the original staircase survives

unaltered. Originally, the facade (east side) had cross windows

on the first floor, and mullioned windows (bolkozijn) on the second

floor, as is shown in a lost early drawing of the house. The north

wall had windows flanking a jambless fireplace on the first floor,

and the south wall had windows on the second floor on either side

of a fireplace. The original disposition of windows on the back

(west) wall cannot be determined.

4A. One of the north wall windows- that on the east side of the

first floor fireplace has survived intact except for the leaded

glazing in its top openings. The interior of the frame, and the

insides of the shutters retains the original paint. The frame is

now a yellowish color and may originally have been white (?). The

shutters, of batten construction are painted to look like they

are panelled, with

red margins and dark blue, almost black centers (Prussian blue?)

surrounded by a margin of white corresponding with the moldings

on the battens. While the frame has rabbets for casements, there

is no indication that such were ever fitted. Considering the 'mansion'

status of this house, the absence of casements is something of a

surprise! (see D.V.A./N.A., PL 74A)

4B. In the timber-framed Coeymans

'secondary house', the age of which has not been determined, but

is probably early 18th century, there is a half-cross-window (kloosterkozijn)

in the north side wall which at one point had a fireplace built in

front of it. The east (gable) wall of cross-bond brickwork, originally

had two similar windows, later removed and the openings filled with

brick. The existing unit had its outer surfaced mutilated to facilitate

weatherboarding being applied over it. While the bottom opening has

rabbets for a casement, there is no evidence of one being fitted.

(See D.V.A./N.A., PL 75B)

5. Bevier-EIting house, one-and-a-half story, gable-fronted

stone house built in the 1690's with two additions, the earlier one

built in the 1720's. Located on Huguenot Street in the Village of

New Paltz. The house faces west. In the south wall of the first addition

there is a cross-window frame that had been modified for double-hung

sash by the removal of the transom and mullion. An additional jamb

was added within the opening against the east jamb to reduce the

width of the opening. The original east jamb retains both its shutter

rabbet, and that for the leaded glass. The projecting head is grooved

on the underside for the reception of the glazing in the top openings.

This frame does not have internal rabbets for casements. (See D.V.A./N.A.

PI. 74B, 75A)

6. Pieter Winne house, 1723. One-and-a-half

story timber-framed house covered with weatherboards except

for its partially brick facade (east gable wall)of cross-bond. In

the back (west) wall two studs survive that had formed the jambs

of a cross-window. They are of cedar, the only use of this wood found

in the house. The head of the window was formed by the end anchor

beam. The transom, sill and mullion had been removed. The outer

face of the frame had been cut back to the bottoms of the shutter

rabbets so that weatherboards could be installed over the window

opening, into which a 19th century window had been inserted. Again,

in this house, although interior rabbets were provided for casements,

there is no sign they had ever been fitted. A similar window had

once existed in the brick facade (east) wall. One side of the opening

in the brick survived. The other side had been destroyed when a

later, wider window unit was installed. The top of this window

consisted of the end anchor beam, hi which the mortices for the

jambs and the mullion survive, as also the groove to house the

top edges of the leaded glazing. This groove runs the whole length

of the timber and also accommodated the glazing for the transom

of the doorway. (See D.V.A./N.A., PI. 128, 129)

Pieter Bronck house, said to date to 1663 but

probably later. One-and-a-half story gable-fronted stone house.

What is probably a cross-window frame survives in altered condition

in the front (east) wall, just to the south of the centerline.

This frame has been investigated by William McMillen, but certain

details are obscured by the later addition of trim pieces, inside

and out. The opening to the north of this window originally was

a transomed doorway which probably was made into a window when

the older stone house was connected to the 1738 Leandert Bronck

house? (See D.V.A./N.A., PI. 9, top left)

John R. Stevens, December 2005

Marion Stevens in front of the

Jan Martense Schenck House

As reconstructed in the Brooklyn Museum

We understand that the house has been disassembled and moved to a

larger room in the museum. Will the wood muntins in the window sash

be replaced with lead cames and iron guard bars as they would have

been in 1670?

Copyright

© 2006.

Hudson Valley Vernacular Architecture. All rights reserved. All

items on the site are copyrighted. While

we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site

by copying it, or downloading it; this information is

copyrighted and not to be reproduced

for distribution, sale, or profit.