|

Dutch

Barn Preservation Society

Dedicated

to the Study and Preservation

of New World Dutch Barns

NEWSLETTER

FALL 2003, Vol. 16, Issue 2

INFLUENCES

ON NEW YORK'S EARLY DUTCH ARCHITECTURE

Presentation by Shirley W Dunn; Conference on New

York State History, Bard College, June 6r 2003.

The purpose of this paper is to give a voice to an architectural

form which some readers may not know about. This form, one of the

very first farm buildings built by early Dutch settlers in present

New York, has disappeared, but it has had a striking influence.

We must set the scene: When you think of a Dutch-style house, you

have in mind steep-sloped Dutch roofs, originally developed to

support thatch or tiles in the Netherlands. With a few adjustments,

these proved practical in areas of Dutch settlement where heavy

snows were common, such as the Hudson Valley and Long Island. [Figure

1: Bronck House] An example is the Pieter Bronck House of Coxsackie,

probably built in 1663.

Figure #1. The stone house erected about 1663 by

Pieter Bronck at the present Coxsackie is now a museum supported

by the Greene County Historical Society. Photo by Robert Andersen.

The Bronck House seems to be the oldest nearly intact house in

the Dutch style remaining in New York State. It undoubtedly survived

because it was built of stone, rather than wood. My guess is the

stone was chosen for safety, in consideration of Peter Stuyvesant's

war against the Esopus Indians, a war being waged only a few miles

away near present-day Kingston. The Bronck House is wider than

deep, which makes it doubly special. The original front door was

in front, in the location of the present right front window, shown

in the picture. As evidence of the doorway, besides obvious changes

in the brickwork, there is the trap door to the cellar, with a

stair below it, which remains in the floor in front of where the

door was located, to the present time.

Special barns that we associate with Dutch framing styles also

were built in the seventeenth century - and some from the eighteenth

century, erected by Dutch descendents, still survive. They all

seem to have the same underlying framing pattern, which is surprising,

because barns in the Netherlands exhibited great variety. These

special "Dutch"

barns of the Hudson Valley and Long Island and New Jersey were

practical for storing and threshing wheat, at one time the major

crop of upstate New York. As a result, we often say that this barn

was a wheat barn, but it was used for other kinds of grain in the

Netherlands. [Figure 2: Van Bergen Dutch Barn] A photograph presents

the exterior of the ancient Marte Gerritsen Van Bergen barn in

Leeds. In 1928 it was still in good condition. This barn is believed

to be the one built by the year 1680, when it was mentioned in

a contract.(1) An interior view of the Van Bergen Barn [figure

3: interior framing] shows the anchor beam braces with lightly

curved soffits (undersides), typical of early Dutch construction.

The large horizontal anchor beams of this barn were about twenty

inches deep. On the saplings overhead hay and grain was stored.

The Van Bergen barn survived until a few decades ago, but by the

1970s its roof was off and after that the building tumbled down.

It is now gone, the site bull-dozed.

Figure #2. The Van Bergen Dutch

barn at present Leeds, New York, as it appeared in 1980. Photo

courtesy Dorothy Scanlon.

The interior of the Van Bergen barn of c. 1680

shows curved soffits on the anchorbeam braces.

Despite a popular impression, the steep-roofed houses and the

Dutch barns were not the only important forms established here

by the Dutch. To understand this perhaps surprising statement we

can go back to the beginning of Dutch farm settlement in the Hudson

Valley in the seventeenth century. Much of what we know about the

farms comes from the many letters of Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, a

Dutch merchant who established Rensselaerswyck in the area of present

Albany and Rensselaer counties.

The first upstate farm was established in 1631 by agents of Van

Rensselaer on fertile Castle Island, now the location of the Port

of Albany. There one large farmhouse was built in 1631 for Kiliaen

Van Rensselaer's first upstate farm family and a few farm helpers.

This farmhouse was described by Van Rensselaer as "a convenient

dwelling, the side and gable built up with brick, the dwelling

[as] long and wide as required."(2) He also wrote in a letter

about this building, "The house was furnished with all kinds

of implements and necessaries for the animals and the comfort and

support of the people and what further was needful."(3) Surprise!

The structure contained not only living quarters for the farm family

and the farm help but for animals in their stalls, as well as storage

and work areas, (More than thirty years later, this large frame

and brick farmhouse on Castle Island was washed away in the flood

of 1666.) Having the house and barn under one roof occasioned no

special comment in the 1600s because such buildings were common

in northern Europe and, in fact, are still erected, especially

in the Netherlands. Such a farmhouse, with its hay barracks and

even a nice Dutch wagon with outsize back wheels, was drawn on

a land survey in the Netherlands about 1600.(4) [Figure 4: survey]

A closer view of a Dutch barrack shows how a farmer stowed a similar

wagon in one.[Figure 5: Hay barrack]

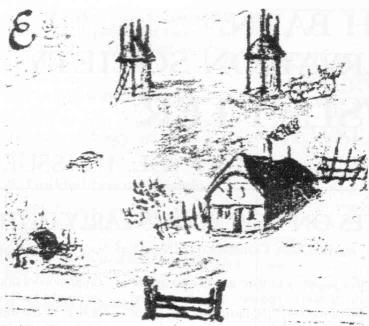

Figure #4. A Netherlands farmhouse with attached

barn, with its accompanying hay barracks and a wagon, was drawn

on a Dutch land survey about 1600. From Van vlechtwerk tot baksteen,

by J.J. Voskuil, Stichting Historisch Boerderij-Onderzoek, Arnhem,

1979. Used with permission.

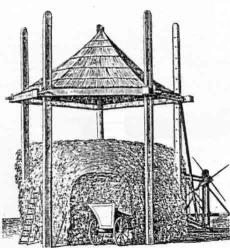

Figure #5. A Dutch hay barrack, also called a "Haystack."

From J. Ie Francq van Berkhey, Natuurlijke History van Holland,

VoI.IX, part 1 (Leiden, 1810).

Diagonally across the Hudson River from present Albany, the second

Van Rensselaer farm was established that same summer of 1631 near

a pine grove in an area called the Greenbush, meaning the pine

woods. The location is now within the City of Rensselaer. In 1631,

Roelof Jansen from the coast of Sweden became the first farmer

at the Greenbush farm. Roelof Jansen came to the area in 1630 after

a stop in the Netherlands. With him were his wife, and the now

famous Anneke Jans, and their three daughters. A son known as Jan

Roelofsen, was born after Roelof and Annetje arrived. Aiding Roelof

Jansen and his family with the farm work were two farm helpers,

Claes Claesen and Jacob Goyversen, both from Fleckero, Norway,

who came over in 1630 with Jansen.(5)

One large rectangular house for all these people and for their

livestock, grain storage, and work space was erected. It was, apparently,

similar to its mate built on Castle Island. The Greenbush farmer

began with four horses. Cows for his farm were detained down river,

but a few arrived the next year. Other buildings on the farm included

a Dutch-style hay barrack of four poles, fifty feet high, a barn

or shed, and a sheepcote.

This brand new Greenbush farmhouse accidentally burned in 1632,

but a replacement was built as quickly as possible. Fortunately,

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, writing from the Netherlands, described

this new building: He said the people ". . . built again another

brick house, 80 feet long, the threshing floor 25 feet wide and

the beams 12 feet high, up to the ceiling."(6) The description

states that the replacement building was similar to the previous

one at Greenbush, and suggests it also was like the one built on

Castle Island across the river in 1631, which had the sides and

gable end built up with brick. The building was to be as long as

needed. As the Dutch foot was shorter than today's measure, the

actual length of the Greenbush building was about 72.5 feet and

the threshing floor just short of 23 feet across.

A few other farmhouses of this European type were erected in

the present Albany area within a few years. A small one burned

down on an east side farm south of Greenbush in 1640. Although

the farmer was not injured, the horses (mares, actually) in this

building were killed with the loss of their expected foals.(7)

On the other side of the river, archeological evidence of a building

over one hundred feet long, thought to be the one described in

a 1643 letter by Arent Van Curler, was unearthed about 1974 by

archeologist Paul Huey and others at the farm called the Flatts,

north of Albany. Van Curler's letter included valuable details

about arrangements: his farm hands were to sleep in an attic room

over the family's living quarters, while the foreman would have

his bunk in the barn section.(8)

Figure #6. Detail from the Manatus

Map of c. 1639 (copied in the 1660s), shows the two farms of

Wolfert Gerritsen in present Brooklyn. Harrisse collection, Maps,

Library of Congress.

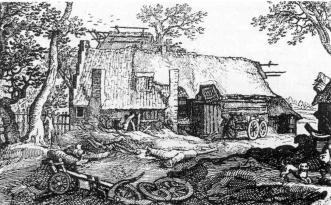

Figure #7. A seventeenth century barn in the Netherlands,

in the Gooi region, suggests the likely appearance of the farmhouses

built by Kiliaen Van Rensselaer at Creenbush and on Castle Island.

Detail from an engraving, "Tobias and the Angel," by

Abraham Bloemaert, 1620.

In addition, there are reports of similar buildings from the first

farms at Manhattan, where some of the men employed by Kiliaen Van

Rensselaer worked in 1630 before they came upriver. In particular,

Wolfert Gerritsen was in charge of assembling livestock at Manhattan

and shipping it up to the Fort Orange area for the new Van Rensselaer

farms. Two farms, each with a rectangular long farmhouse as well

as a hay barrack, were identified on a 1639 map of Manatus (Manhattan)

and environs as those of Wolfert Gerritsen. [Figure 6: Manatus

Map]

Fortunately, similar farmhouses were occasionally depicted in

the Netherlands. [Figure 7: Detail from Tobias and the Angel] A

Dutch artist, Abraham Bloemaert, in 1620 sketched a 'farmhouse

from the region called the Gooi or Gooiland.(9) The long building

fits the description of those planned for Greenbush and Castle

Island. Bloemaert has been criticized for making fun of the farms

by making them look run-down. Nevertheless, his picture is invaluable.

The stepped gable he showed was made of brick, as were the walls

and chimney of the living section on the left-hand side of the

picture. The resemblance to the farm houses built by Van Rensselaer's

orders is clear. Van Rensselaer had noted that the gable end of

his farmhouse on the Island was to be made of brick. In the picture,

the roof of the living part was covered with tiles, while the attached

barn section on the other end had wood siding, with a thatched

roof. Looming behind the living section was a hay barrack - this

one with a gable roof high in the air.

Clues to the interior arrangement of the farmhouse include the

front chimney serving the fireplace in the residence, which, in

the Dutch style, would not have a built-in oven. Rather, an extra

chimney at the center of the building served a separate oven for

baking. Documents suggest the farmhouse at Creenbush also had such

a special baking oven. In the early 1640s, Willem Juriaensz, a

baker, was paid for baking on the farm at Creenbush and for going

around to bake at Van Rensselaer's other farms. Willem Juriaensz

also visited and baked at the farm of Arent Van Curler, with its

long farmhouse on the Flatts, mentioned above.(10)

The reference to brick in construction changes common notions

of architectural history. Father Isaac Jogues had said of a visit

to Fort Orange in 1643 that the houses were "merely of boards

and thatched. As yet there is no mason work except the chimneys."(11)

His description is widely quoted as a snapshot of the wooden housing

of the period. However, Jogues, rescued from the Mohawks, was hiding

within Fort Orange. He did not notice that the large farmhouses

in the distance at Creenbush and Castle Island were constructed

in part with bricks. The bricks, sent by Kiliaen Van Rensselaer,

were probably the small yellow ones found on very early sites in

the Albany area.

Van Rensselaer, who contracted with Dutch farmers to go overseas

to the Hudson Valley to work on his farms, never let go of the

land, as we all understand, and he definitely pinched pennies.

Always concerned about costs in his overseas colony, Van Rensselaer

wanted an economical solution to housing his tenant farmers, their

families and their help, as well as the valuable farm animals.

These animals he supplied for the farm and from them he shared

the increase. It is not surprising that he selected a building

well-known to him to meet these requirements. Scholars have wondered

where this particular farmhouse type, built on Kiliaen van Rensselaer's

orders, might have originated?

A land speculator, Kiliaen van Rensselaer had invested in farmland

in the Gooi, the Dutch region of sandy soils where rye and oats

were cultivated. Interestingly, the poor soil there was not suitable

for wheat.

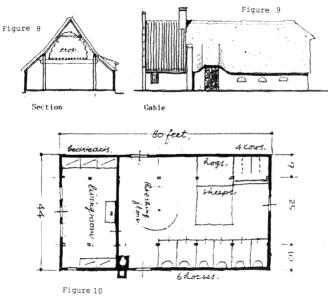

Figure

8- 10. Drawings by Jaap Schipper, a contemporary Netherlands

restoration architect, shows the appearance of a Gooi "Ionghouse" of

the seventeenth century. The interior layout includes a bakeoven

at the partition. Another sketch shows the framing, which Dutch

Barns followed for two centuries. The brick living section with

standing gable was roofed with tile, while the barn at rear was

thatched. Figure

8- 10. Drawings by Jaap Schipper, a contemporary Netherlands

restoration architect, shows the appearance of a Gooi "Ionghouse" of

the seventeenth century. The interior layout includes a bakeoven

at the partition. Another sketch shows the framing, which Dutch

Barns followed for two centuries. The brick living section with

standing gable was roofed with tile, while the barn at rear was

thatched.

This is the same region where Abraham Bloemaert sketched a typical

farmhouse, noted above. The special farmhouses built there combined

the tenant's home with stables, threshing floor, and overhead crop

storage under one roof. These rectangular Gooi farm buildings were

called longhouses. I believe these familiar and practical structures

of the Gooi were the ones Van Rensselaer copied in the Hudson Valley.

Such inclusive structures would be an efficient and economical

solution for new farms anywhere.

Restoration architect and historian Jaap Schipper of Amsterdam,

the Netherlands, prepared a few sketches for me of a farmhouse

of the Gooi type, [Figures 8, 9, 10: Schipper drawings]. The typical

Gooi farmhouses known to Schipper echo the early 1600s drawing

by Abraham Bloemaert amazingly well, both inside and out. The brick

living section with its parapet gable front was roofed with tile

while the barn at the rear was thatched. (Brick was practical and

fire-safe, but it also was used for show.) Schipper, moreover,

shows the interior plan. A bake oven is located at the partition,

just as it was in Bloemaert's sketch. However, in Schipper's drawing,

the main chimney happens to be at the back of the living section,

where there was a wall. The circle indicates the threshing floor.

The family home is at the left front, and boxes around the walls

depict built-in bedsteads. The workers probably slept above in

the loft room over the family dwelling.

One detail of Schipper's drawing shows a cross-section of the

framing of the barn. The crop was placed on saplings just as it

was in later Dutch barns in America, as you saw in the Van Bergen

barn. The anchorbeams were supported, not by the outside walls,

but by posts on each side of the threshing floor, also as it was

done in American Dutch barns. Note that a raised section of the

roof on the side accommodated the height of the wagon door. Most

importantly, outsi.de aisles for stalls flanked the threshing floor

on both sides. These aisles are specifically mentioned in early

Albany barn contracts. The roofs of some early barns, including

possibly the Van Bergen Bergen barn which you saw, may have had

a roof slope of two different pitches, with a "break" over

the aisles. The Bloemaert sketch hints at a curve or change in

the slope of the roof, but it may merely reflect the sagging of

the rafters.

NEWSLETTER

FALL 2003, Vol. 16, Issue 2, part two

|